Old Moscow, favorites

![Yuri Eremin.

Pomerantsev lamp post. Moscow, [1929].

Artist’s silver gelatin print.

Alex Lachmann’s collection](/upload/iblock/eb7/eb78334024efa81376965aa0a46d4d51.jpg)

Yuri Eremin. In the stream. 1920. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Portrait of a woman (Secession). 1914. Bromoil. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Barges with watermelons on the Kutum River. 1929. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Spring. Early 1920s. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Luffa. Late 1920s. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Wind in Venice, 1910. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Ships. Sebastopol. 1930. Bromoil. Alex Lachmann’s collection

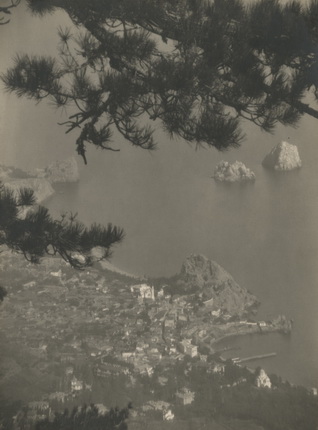

Yuri Eremin. Gurzuf. Avinda. 1925. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Church of Christ the Saviour. View from the A.S. Pushkin Fine Art Museum. Moscow, late 1920s. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Yuri Eremin. Pomerantsev lamp post. Moscow, [1929]. Artist’s silver gelatin print. Alex Lachmann’s collection

Moscow, 22.10.2014—11.12.2014

exhibition is over

Share with friends

From the collections of Alex Laсhmann and the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow

For the press

MAMM presents a retrospective of Yuri Eremin, one of the celebrated Pictorialist photographers, as part of ‘Classics of Russian Photography’ and ‘The History of Russia in Photography’, programmes the museum has pursued since 1997. The Russian school of Pictorialist photography takes a special place in the history of world photo art, and the Pictorialists’ work is splendidly attuned to the context of art worldwide. Yuri Eremin, Alexander Grinberg, Nikolai Andreyev and Nikolai Svishchov-Paola represented Russia at major international photography exhibitions and salons in Europe, the USA and Japan, frequently winning the most prestigious awards.

After first appearing on the international photography scene in the late 19th century, Pictorialism had largely exhausted its aesthetic potential by the mid-1920s. Post-war Europe turned to other genres and art movements, but it enjoyed a renaissance in the USSR for several years. The Pictorialists strove to equate photography to painting, mainly using a soft-focus lens and specific, very sophisticated printing techniques. Pictorialist photography challenged the documentary image. In the new Soviet state Pictorialist photographers were in no hurry to adopt Soviet slogans or enthuse over revolutionary achievements. Their subject matter was mostly confined to landscapes, nudes and genre scenes. Soviet critics, like the foreign press, regarded them primarily as the aesthetic opposition to militant Soviet ideology.

Yuri Eremin was born in 1881. He travelled extensively in Europe, studying the work of great Italian and French painters, and this hugely influenced his worldview and aesthetic principles. Eremin was always keen to continue his self-education, too: in Paris he attended drawing classes at the Académie Rodolphe Julian, took a philosophy course at the Sorbonne and studied photography ‒ one of his first landscapes in the Pictorialist manner earned the gold medal at an international photography exhibition in Nice.

In Moscow after the war Eremin opened the Secession Photographic Studio, which functioned from 1918 to 1922; attended the VKhUTEMAS Higher Art and Technical Studios; began photographing and sketching the historical and cultural monuments of Russia; started work for the Press-Cliché Agency (forerunner of the TASS photojournalism agency) and Exportizdat; became editorial board member of the magazine Fotograf; headed the MUR (Moscow Criminal Investigation Department) photo laboratory; and taught at VKhUTEIN (Higher Art and Technical Institute), the Polygraphic Institute and MARKhI (Moscow Architectural Institute), etc.

In the late 20s Eremin actively exhibited his work (in 1928 alone he took part in seven international shows in Europe and the USA) and no less actively defended Pictorialist ideas at public photography debates where at the time discussion focused on aesthetics. Alexander Rodchenko, who presided over a galaxy of young Modernists and Constructivists, wrote in the magazine Novy LEF in 1928: ‘It is not so much painting we are struggling with (it is dying anyway), but rather with photography ‘à la painting’’... Curiously, in the late 1930s Rodchenko, who had long opposed the aesthetics of Pictorialism, became weary of the non-stop revolutionary transformations that inspired his early work and created splendid photo series on ballet, theatre and the circus in the Pictorialist manner.

In the mid-1930s aesthetics yielded to ideology. Instead of photographic debates on the advantages of different techniques for printing images or the opportunities offered by different optical devices, discussion turned to ‘political short-sightedness’ and the hunt began for enemies of the new world order. Socialist Realism was declared to be the only admissible means for representing reality.

For a while the Pictorialist photographers continued working and participating in important exhibitions such as ‘Masters of Soviet Photography’ (1935), but they attracted wholly negative press reviews. The magazine Soviet Photo accused them outright of ‘a predilection for remnants of the pre-Revolutionary culture of noble manor houses and the architecture of old Moscow’ and ‘depicting scenes of rural life during the period of Socialist reorganisation of the countryside that are useful to no one’, declaring that ‘the working class has no need of nudes’.

During the debate ‘On Formalism and Naturalism in Art’ in 1936 Pictorialist photography was branded ‘bourgeois’ and ‘ill-timed’ ‘Turgenev-ism’ whose ‘decadent frame of mind prevented’ the working class from creating the new art.

Yuri Eremin was one of the few who stayed faithful to the end to the stylistics of Pictorialism, continuing to defend not only himself and his aesthetic views, his picture of the world, but also the art of the Modernists, engaging as far as possible in polemics with the Socialist Realists.

After the aesthetics of Socialist Realism was transformed into an accessory of the ideological machine, the opportunity for debate became simply impossible and the moral persecution of artists led to physical repressions. Alexander Grinberg was sent to Stalin’s labour camps under the ludicrous pretext of ‘dissemination of pornography’ and Vasily Ulitin was exiled from the capital. Nearly all the Pictorialist photographers were deprived of the right to practise their profession.

Nikolai Petrov headed a legal expertise service, Leonid Shokin became a newspaper photojournalist and Nikolai Svishchov-Paola went to work in the House of Pioneers. Yuri Eremin locked himself in the bathroom of a communal apartment and secretly printed Pictorialist prints in miniature format: this was his escape from Socialist reality, an attempt at ‘quiet resistance’ to the new laws governing art. Any one of the images Eremin printed would have been sufficient to condemn him.

During the Second World War Yuri Eremin worked closely with GUOP (Chief Administration for the Protection of Monuments). In December 1944 he sold them more than 2500 negatives. In 1947 Eremin became a photojournalist for TASS, the official Soviet news agency. In 1948 Yuri Eremin died suddenly from a heart attack.