Portraits

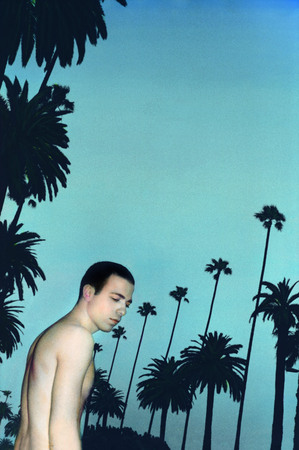

Youssef Nabil. Self portrait, Beverly Hills. 2008. © Youssef Nabil. Courtesy Galerie Volker Diehl

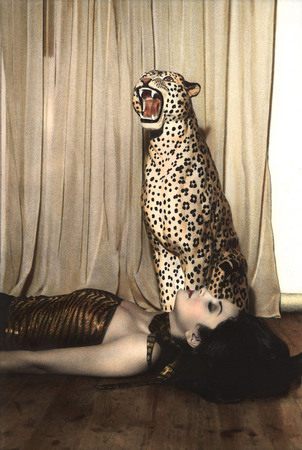

Youssef Nabil. Shirin Neshat, Casablanca. 2007. © Youssef Nabil. Courtesy Galerie Volker Diehl

Youssef Nabil. Rania, Cairo. 2002. © Youssef Nabil. Courtesy Galerie Volker Diehl

Moscow, 28.03.2009—4.05.2009

exhibition is over

Zourab Tsereteli Gallery of Fine-Arts

19, Prechistenka street (

opening hours: 12:00 - 20:00, Friday 12:00 - 22:00, Sunday 12:00 - 19:00, day off - Monday.

Tel: + 7 (495) 637-25-69

Share with friends

Curator: Olga Sviblova

Courtesy Gallery Volker Diehl

Courtesy Gallery Volker Diehl

For the press

I am not quite sure whether I am dreaming or remembering,

whether I have lived my life or merely dreamed it...

Eugene Ionesco,

Present Past-Past Present, 1968

The hand-coloured photographs of Youssef Nabil are a personal aesthetic form of life in death and death in life — they are both memory and living memorial.

As with all photographic portraiture, and as Roland Barthes long ago observed, there is always a form of initial death in a photograph. Insomuch as all photographs, and particularly portraits, are of a moment or passage of time that is no more. They portray inevitably a lost reality — a once-truth that has turned into a present-fiction. Yet with the use of a complex hand-colouring approach (a system first mastered and used in the early period of photography in the 1840s) Nabil’s photographs are able create a metaphorical elision of the obvious sense of time and fixity. Nabil himself makes the poetic point clear ‘...and that everything is changing too, including us. I want to photograph everything I love, I want to keep part of them with me, I want them to live forever through my work’.

His early works draw on close analogies with film, and particularly Egyptian film stars and sources of the 1940s and 50s, where Nabil evokes a feeling of displaced sensibility brought into the present. It is almost as if the glamorous film age lifestyle of the bon vivant King Farouk’s Egypt has been somehow miraculously been restaged. The sitters take on a appropriated form of estranged re-embodiment and presence, that carefully manipulates Western and Orientalist tropes of pre-imagined perception. Inferences of dreams, desires and their projections, the sexual unconscious, and personalized identifications follow. There is also a strong sense of nostalgic loss, and an intense yearning for an authentic ‘otherness’ within the photography of Nabil. The sitters are thereby drawn out and visually magnified through a feeling of opaque beauty, and the familiar time-space of the images escape into a hazy oblivion of undefined duration.

Nabil’s intimate self-portraiture is closely linked to dream and the desire-illusions that the cinema of the past was so readily able to create, and with which he intimately identifies. Indeed, at times the self-portraits of Nabil appear to parallel the world of extracted film stills. His use of male beauty, both his own and that of his sitters, creates an unblemished series of fantasy images. They are images that at times touch upon the Caravagesque, but without the Baroque sense of blighted infection. In recent years there has been an increased concentration on bust portraiture of international artists, writers, and film celebrities. These include Louise Bourgeois, Mona Hatoum, Tracey Emin, Shirin Neshat, Ghada Amer and Julian Schnabel, and such film luminaries as David Lynch and John Waters. However, for Nabil the choices are shaped as much by shared interests and personal friendships rather than fame, ‘I don’t want to see anyone I love dying... I won’t let them die before me’.

Hand-coloured prints in the early twentieth century were associated with commercial portrait photography and with popular forms of artistic transmission. It is a major achievement of the photography of Youssef Nabil that he has been able to redeem a forgotten and meager art form, and transform its use and understanding into ‘high’ or fine art. The effect is a unique fusion of photography and painting, one that mediates the space between Photo-realism on the one hand, and the conventions of film and/or portrait photography on the other.

Mark Gisbourne