Episode 2. Leningrad

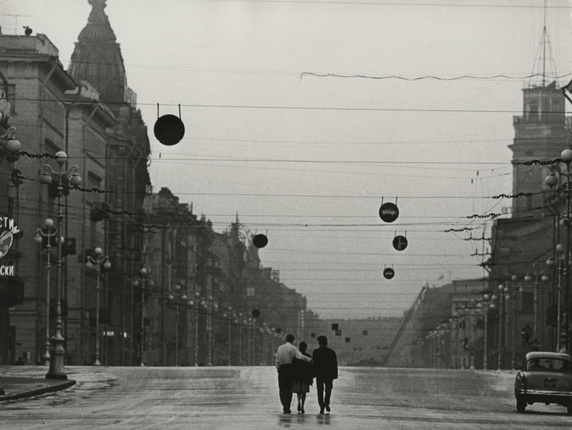

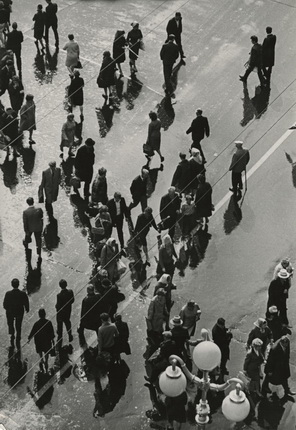

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. From the series ‘Nevsky Prospect’. Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. From the series ‘Nevsky Prospect’. Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography

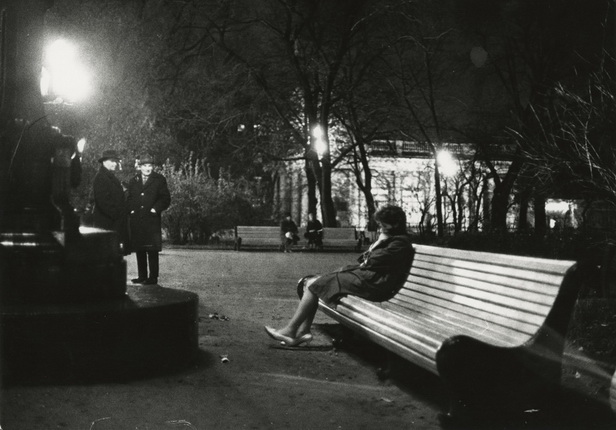

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. Leningrad, Summer Garden, 1965. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. From the series ‘Nevsky Prospect’. Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography

Vsevolod Tarasevich. Untitled. From the series ‘Nevsky Prospect’. Leningrad, 1965. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography

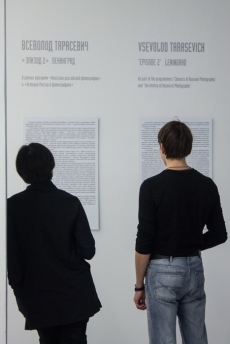

Moscow, 14.11.2014—14.12.2014

exhibition is over

Share with friends

As part of the programmes 'Classics of Russian Photography' and 'Russian History in Photographs', MAMM presents the second exhibition by Vsevolod Tarasevich (1919-1998) – a series of photographs devoted to Leningrad in the 1960s.

For the press

The life and career of Vsevolod Tarasevich was connected to Leningrad, subsequently St. Petersburg, for many years. He began publishing photographs in the Smena and Leningradskaya Pravda newspapers while studying at the Leningrad Electro-Technical Institute, and later, in 1940, became a press photographer for the LenTASS picture chronicle. Throughout the war he worked as photojournalist for the North-West Political Administration, then for the Leningrad front, and after the war with Vecherny Leningrad newspaper. One of Tarasevich’s most famous series was shot in Leningrad during the blockade and in the ruins of Peterhof and Pushkin.

After moving to Moscow Tarasevich become staff correspondent for one of the most influential information agencies in the USSR, the Novosti Press Agency (APN). While employed at the agency Tarasevich often travelled to Leningrad on assignments. Most of the photographs shown in this exhibition were taken in the mid-1960s on commission for APN, as proven by texts pasted on the reverse of the image as material was submitted to the editorial office.

In Leningrad Tarasevich created several quite diverse photographic series. His social reportage about a Leningrad juvenile detention facility, Leningrad State University and the Electro-Technical Institute date from the 1960s, and later, in the early 1970s, he produced the series ’LOMO Factory’ and ’Four Tasks of the Lathe Operator Moryakov’, about a Leningrad Construction Machine Factory (Stroimash) worker — classic Soviet reportages illustrating the factories’ achievements and forming an image of the ideal life of a Soviet worker.

But the photographs chosen for this exhibition actually show Tarasevich as one of the most striking exponents of the Thaw. These images are a hymn to the free humanistic photography that in those years included not only the Soviet Union, but also Europe and America. A free handheld camera and lack of posed human subjects and false smiles are distinguishing features of the ’Leningrad series’. The move away from posed shots had fundamental ideological significance at the time. When reminiscing about his father, Tarasevich’s son commented on his working method: ‘He tried to foresee the possible outcome of a situation and thought in advance of possible and impossible coincidences of circumstance, some of which indeed occurred and were captured by his lens...’ Apart from recognisable views the series includes numerous street photographs of city dwellers. Tarasevich pays remarkable attention to detail, to the clothing, expressions and gestures of the people captured by his camera. From the negatives we can see a vast number of takes that were photographed before he snapped the one frame that subsequently found its way into print. Many of the subjects and objects that attracted the photographer’s attention are repeated: the urban fabric is woven from wet streets, benches, telephone boxes, newspapers, books, bunches of flowers and umbrellas; the heroes of these images are frequently waiting for someone or in a rush to get somewhere. These photos partly refer to the traditions of Soviet cinematography and at the same time to the visual canon established by Henri Cartier-Bresson’s European reportage photography. It is no coincidence that Cartier-Bresson was one of the few photographers Tarasevich admired and took as an example.

Tarasevich dreamed of publishing an album devoted to Leningrad. An application Tarasevich wrote in 1995 for a book provisionally entitled ‘Main Street’ is preserved in the Multimedia Art Museum archives. Here he suggests that the book be comprised of mainly later works (1980s-1990s), but clearly from his description of subject matter the idea for a book on Leningrad had first occurred years ago, and many of the images — from children playing in a park to gravestones in the cemetery — hark back to the early series created in 1960s Leningrad.