Street, Art and Fashion. New Photography from New Russia. 1991-2005

Alexander Abaza, Valery Shchekoldin, Michael Evstafiev, Igor Moukhin, Vladimir Semin, Boris Kudryavov, Sergei Chilikov, Eugeny Mokhorev, Nikolai Polissky, George Pervov, Evfrossina Lavroukhina, Vladimir Friedkes, Vlad Loktev, Vladimir Glynin, Vlad Monroe, Gleb Kosorokuv, Arsen Savadov, Oleg Kulik, AES+F, Andrey Molodkin, Alexey Beljaev-Gintovt, Vladimir Vyatkin, Boris Bendikov, Leonid Tishkov

Michael Evstafiev. The Red Series. Moscow. 1991

Alexander Abaza. August-91. Moscow. Author’s property

Boris Kudryavov. Mirror of War (Grozny). 1996. Author’s property

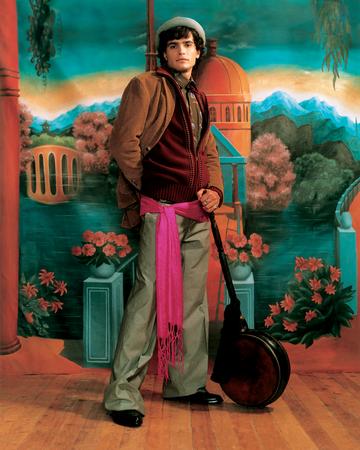

Vladimir Glynin. Around of the world. Style: Galina Smirnskaja; Assistant to the photographer: Jury Katkov; Make-up: Elena Usanova; Models: Michael Vasiljev, Dmitry Shevchenko, Alan Al-Mohammed, Levan Gomiachvili (President)

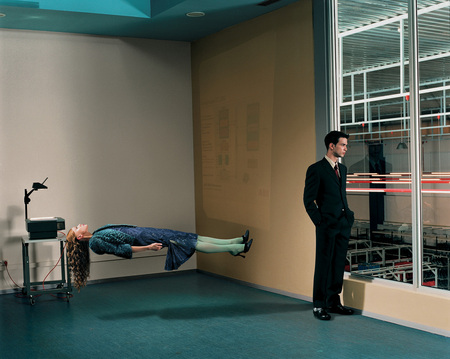

AES+F. Action Half Life. 2003. AES+F

Nikolai Polissky. Tower. 2000

Gleb Kosorokuv, Andrey Molodkin, Alexey Beljaev-Gintovt. Pole. 2002

George Pervov. Untitled. 2003

Vladimir Semin. Pensioner N.M.Kravets. October, 1997

Leonid Tishkov, Boris Bendikov. From “Private moon” series. The collections of the authors

Vladimir Vyatkin. All quiet on the Chechen Front. 2000

Sergey Tchilikov. From “Russian Regions” series. 1993 – 1995

Vladimir Friedkes. Trust. The project for L’OFFICIEL Magazine. 1999

Evfrossina Lavroukhina. Comme des Garçons. 2003

Evfrossina Lavroukhina. Divertissement. 2004

Vlad Loktev. 1:0. The project for L’OFFICIEL magazine. 1999

Oleg Kulik. Lolita with Variations. 1999

Eugeny Mokhorev. Sasha and Kostia. (Blank shot over a head). 1999. From “The Teenagers of Saint Petersburg” series

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monro. Vladimir Lenin. 2002. From “The Life of Remarkable Monroes” series

Igor Mukhin. Moscow. 1998

Arsen Savadov. Donbass. Chocolate. 2001

Valery Shchekoldin. Mohammedan of a Rebel. From “The Chechen Syndrome” series. 1999

Antwerp, 5.10.2005—8.01.2006

exhibition is over

FotoMuseum Provincie Antwerpen

Waalse Kaai 47, 2000

Share with friends

For the press

The project «New Photography from New Russia.

The Perestroika («Reconstruction») epoch of the late eighties legalized Soviet unofficial art, the so-called «underground». This was a period of its unprecedented prosperity, when it became widely known and appreciated both at home and abroad. However, in those days local photography did not attract much attention either in the West or in the USSR. For years it faithfully served the communist regime, thus ceasing to be regarded both as a form of a document or as a work of art. The repressions of the middle and late thirties, aimed against those artists who belonged to the pictorial or modernist trends, led to the absolute predominance of Socialist Realism esthetic. Its rigorous rules limited the creative abilities of the masters, transforming photo-reportage into production shots, which had little connection with reality. The strict banning of any «formalist» experiments slowed down the development of a new artistic language. What made things even worse was the isolation, lasting for more than fifty years, of Soviet photography from the esthetic innovations and cultural context of the rest of the world.

In 1991 Russia entered a new era. The failed August putsch, plotted by communist hard-liners, marked the transition from the Soviet epoch to modern Russian history. In the early nineties politics began to permeate everyday life to such an extent, while any form of censorship practically disappeared, that the opposition official-unofficial vanished, and the traditional strategy of dealing with forbidden ideological issues lost its sense. Artists had to look for new themes, for new forms of expression and for a new artistic language. The possibility of expanding one’s range of subjects after certain restriction disappeared (i.e. shooting the so-called negative features of life: social problems, poverty, wars, terrorism, etc.) primarily affected the field of photo-report. At the same time we can see the emergence of an interest in the individual personality and its psychology, opposing the basic principles of Soviet photography rooted in the normative and the collective.

In the early nineties a new group of photographers took full advantage of the opportunity of being published in the local free press, as well as in foreign editions. These artists also actively participated in various exhibitions, including those accompanying important international festivals (one example is the «International Month of Photography — Photo Biennial» that takes place in Moscow since 1996). Among those who successfully portrayed contemporary Russian life we can name Igor Mukhin, Vladimir Viatkin, Yuri Kozyrev, Mikhail Yevstafiev, Valeri Shchekoldin, Vladimir Siomin, Aleksander Sliusarev, Boris Saveliev, Yevgeny Kondakov, Vladimir Mishukov... Most of them received Russian or international prizes and awards for documentary photography. Owing to these masters Russia gradually learned to adopt a more objective approach to its rapidly changing history, purified from the aura of mythology, which had replaced reality during the Soviet epoch.

There was practically no fashion and style photography in the USSR, except for some of Aleksander Rodchenko’s works, for which Lilia Brik, Varvara Stepanova and a number of close friends posed as models. Fashion magazines as such did not exist, and the very concept of fashion was «unfashionable». Totalitarian ideology demanded that people should sacrifice themselves for the forthcoming «bright future», while the present had to be content with a more than modest level of material prosperity. The poverty of the twenties and thirties, shortage of almost every product, including clothes, made the very existence of fashion industry impossible during the so-called «stagnation epoch» of Leonid Brezhnev. The fashion houses belonging to the State Universal Store and the more recent House of Fashion headed by Slava Zaitsev organized a few shows, but these were attended only by a small circle of people and their representations rarely left the archives of these companies. Today such anonymous photographs convey some of the spirit of the era, but they have no connection with international fashion photography, which speedily developed everywhere in the world and was totally inaccessible behind the iron curtain of Soviet Russia.

In the mid nineties international fashion finally arrives in Russia. The word «fashion» becomes extremely fashionable in everyday life. The most influential fashion houses from Europe, and later from the United States and Japan, open their offices and boutiques in Moscow. Clothes and accessories, which for decades were beyond the reach of Russian people, begin to play a cult role. Possessing them indicates the ultimate achievement of individual self-expression. The «fashion in fashion» time is also marked by the appearance of the Russian editions of illustrated glamour magazines — Cosmopolitan, Vogue, L’Officiel, Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, Gala, etc., as well as local editions dedicated to the sphere of fashion and style. At the same time the advertising business connected with fashion industry is on the rise. All this creates favorable ground for fashion photography, which at first greatly depends on the works of foreign artists. However by the late nineties Russian photographers begin to actively and successfully compete with their Western colleagues, the oeuvre of the latter being now within reach in glamour magazines and at the exhibitions of the classic works of world fashion photography, which since 1998 can be seen at the Moscow Biennial «Fashion and Style in Photography». Among these we can mention one-man shows of Man Ray, Maurice Tabard, Horst P. Horst, Lillian Bassman, William Klein, Jean-Loup Sieff, Helmut Newton, Sarah Moon, Jean-Paul Goude and others. The result of this boom is that in less than a decade there appear such local leaders in the field as Vladimir Fridkes, Vlad Loktev, Mikhail Koroliov, Vladimir Glynin, Yevfrosina Lavrukhina, etc. Russian fashion photography often attracts talented artists, who use the medium to experiment with some of their ideas that are impossible to embody within the context of contemporary art, which in the mid-9Os was not exactly flourishing.

The narrative character of Russian art of the late eighties and early nineties, doubtless influenced by modern literature, left its imprint on national fashion photography. Like contemporary art it often serves as an instrument of social criticism, as is the case with the series «Rich Boy», created by the AEC+F Group: artists Tatiana Arzamasova, Lev Yevzovich, Yevgeni Sviatski and photographer Vladimir Fridkes develop in their fashion shots the theme of childhood, which has become central for their more recent works. The «Rich Boy» series, focusing on the children of «New Russians» as a modern social phenomenon, brings to mind the famous lines of Mikhail Lermontov, the great Russian nineteenth-century writer and poet:

«... Beginning almost with the cradle we are enriched with the mistakes of our fathers and with their belated intellect, // So life tires us like some long journey without an end, // Like food served on a stranger’s feast...»

The superfluous esthetic of New Russian kitsch provokes the irony of Vladimir Glynin, reflected in his series «First Guy» (Playboy Magazine, stylist Galina Smirnskaya). Outright nostalgia for the Soviet past becomes a typological model for a number of shots, including the series «Express» by Mikhail Koroliov.

In its early days Russian fashion photography was not yet limited by strict rules, dictated by the demands of the market. Its subject was often extravagant, and the artists were frequently guided solely by their wild imagination («1:0» by Vlad Loktev, stylist Elena Bakalova, L’Officiel Magazine; «Trust» by Vladimir Fridkes; many works by Yevfrosina Lavrukhina and Olga Tobreluts). In more recent times the influence of globalization slowly leads to the disappearance of a particular national school, even though the individual manner of those who have become influential masters in the field is still clearly evident.

Since the mid nineties photography becomes one of the predominant mediums in Russian art. Leading artists and artistic groups, such as Oleg Kulik, Vladimir Kuprianov, Vladislav Mamyshev-Monro, Ilia Piganov, the AEC+F Group, group «Fenso», Arsen Savadov, Olga Chernyshova, Sergei Bratkov, etc. are now working in this field.

Soviet photographers were busy creating and nourishing socialist myths. Soviet unofficial art and the art of the Perestroika period labored to destroy that mythology. The art of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, including art photography, analyzes the realities of a country in transition trying to obtain stability. It looks with irony at the very process of creating myths and at the same time reflects a renewed demand for this kind of human activity.

In the late eighties Arsen Savadov established a new trend in Ukrainian art, — his post-modernist baroque canvases became widely known both in Russia and in the West. Since the mid nineties, residing partly in Kiev and partly in New York, he begins to create, besides paintings, total photo-installations. The Soviet epoch praised the heroic work of the proletariat, especially that of the miners. They became a major image of Socialist Realism iconography. At the same time people in the Soviet Union, which was striving for «catching up with America and surpassing it», sang some lines from a song that ran: «And even in the sphere of ballet we are ahead of the whole planet». The Stalinist «Empire style» was particularly focused on classical ballet, which was and still is regarded as the principal symbol of Russian classical art. In the mid nineties both professions were stripped of any heroic veils, mainly for the simple reason that Russian capitalism brought equal poverty to miners and to ballet dancers. The former were constantly on strike, while many of the latter left the country. The brutal expression of the absurd, which was brought by the loss of social and individual identity, became the basis of Savadov’s project «Donbass. Chocolate» (1998).

Oleg Kulik is a cult figure of the Russian art scene. His famous performances «Dog-man» became widely known both inside the country and abroad. Reflecting on the era of technology and on the initial stage of Russian capitalism «with an inhuman face», he deconstructs the mythology of such oppositions as human-animal, living-dead, conscious-unconscious. Among many others the latter theme was also banned during the epoch of the Soviet «clear mind» mentality. Extremely expressive sensuality and an acute interest in the nature of the physiological, present in all of Kulik’s projects, is also a characteristic feature of the series «Lolita with Variations» (1999), which attempts to break through our protective social instincts rooted in the Cartesian view of the world.

The works of the «AEC+F» Group (Tatiana Arzamasova, Lev Yevzovich, Yevgeni Sviatski and Vladimir Fridkes) are marked by a strongly critical approach to many philosophical, existential and social issues, their artistic concepts are strikingly articulated and overtly prophetic. Every one of the group’s projects, be it «Suspects» (1998) or «Action Half Life» (2003), represents a sort of provocation, shattering our conventional ideas about good and evil, sin and innocence, vice and virtue... The series «Suspects» is a collection of fourteen portraits of girls under eighteen years old. Seven of them were made in a special prison for young criminals that were accused of particularly brutal murders. The other seven are shots of Moscow school-girls from middle class families. In the installation «Suspects» the photographs of the normal girls and those of the girls-murderers are mixed in a haphazard way. For ethical reasons the truth about those who participated in the project is not disclosed, being known only by the authors. Thus the visitor is expected to guess for himself who in the group was convicted of homicide. In this way we find ourselves in an existential situation reminiscent of Feodor Dostoevski’s novels, asking the question «Could I have been among the suspects»? Apart from existential, the installation also reflects social issues. Children’s and female aggression in extreme cases existed in all epochs and civilizations. But there are times when this phenomenon stands out particularly clear, expressing the crisis of a society that is undergoing radical changes. This was precisely the situation in Russia in the mid nineties: the people, seeing themselves in a stage of transition, with Soviet economic, social and moral norms destroyed, were desperately trying to survive, witnessing the emergence of a new political system. Children and women, who had to go through a particularly strong emotional stress, sometimes turned out to be the weakest link in the social chain and reacted in a destructive and inadequate way.

The series «Action Half Life» is also dedicated to children. It is named after a game which exists in millions of copies across the whole world. What we see here are shots of teenagers that are working in model agencies and were chosen among five hundred candidates. It is interesting to note that today model agencies in Russia are one of the most popular forms of education. In terms of social status they look more attractive for children than traditionally prestigious ballet, art and music schools, and modeling is rapidly becoming more popular than sports or science, — fields of activity which were highly respected during the Soviet era. The backdrop of the project is the Sinai Desert, worthy to serve as an excellent setting for new «Star Wars» films. Like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, the young people here are shown in the moment of temptation, when a terrible weapon of destruction is being handed over to them, but they are still ignorant of the existence of heaven and hell. Placing children inside the world of

Unlike the majority of the artists represented at the exhibition, Nikolai Polisski embodies his utopias not in the realm of imagination, but in real life — on the ground. He works in a small, god-forsaken village, and his collaborator is its almost entire population, which in latter years remained in a permanent state of drowsiness. Polisski’s grandiose performances are inspired by folk traditions and by the experiments of Russian twentieth-century Avant-Garde. The poetic metaphors of the artist, jointly brought to life by the inhabitants of the village, create a playful and festive atmosphere, replete with collective energy. It can be felt in his often gigantic constructions, for example, in a sort of Babylon Tower made of hay, which turns out to be ephemeral, like all global myths of the 20th century. Coming into existence as a part of the landscape, Poilisski’s utopias then dissolve back into it. Thus, the hay tower is eaten by cows.

Russian art of the second half of the twentieth century was primarily focused on local problems, which, on the one hand, was a result of many years of isolation and, on the other, of a shortage of any serious philosophical, political and historical analysis of what was happening in the country. Today the situation is changing — artists are gradually turning to global existential issues, which Russia has in common with the rest of the world. For instance «Fishermen-Plants» by Olga Chernyshova or her series of light-boxes «Dream Street», even though photographed in Russia, deal with universal problems of loneliness and the illusions of our memory.

The exhibition «New Photography from New Russia.

Olga Sviblova, director of the Museum «Moscow House of Photography»