Simulacra and Pseudo-Likeness

Olivier Rebufa, Joon Sung Bae, Karen Knorr, Abigail Lane, Laurie Simmons, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Valerie Belin, Pierre and Gilles

Joon Sung Bae. From “House of the artist” series. 2002. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

Karen Knorr. The art fans. 1998. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

Abigail Lane. “She didn’t need to open her eyes to see”. 1997. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

Olivier Rebufa. Dolce vita. 1994. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

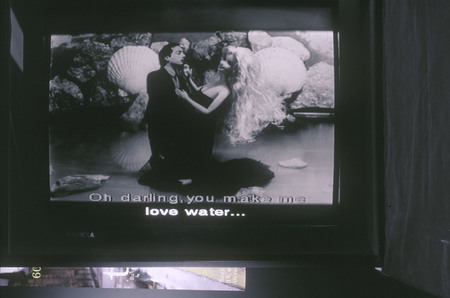

Laurie Simmons. Mexico. 1994. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

Hiroshi Sugimoto. Napoleon Bonaparte and the Duke of Wellington. 1994. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

Valerie Belin. Untitled. 2003. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art, Paris

Pierre and Gilles. Clowns. 2003. Models: Pierre and Gilles. Unique hand-painted photograph, mounted on aluminum. The collection of the National Fund of the Contemporary art (FNAC), Paris

Moscow, 15.03.2005—10.04.2005

exhibition is over

New Manege

Gueorguievski per., 3/3 (

opening hours: 12:00 - 21:00, day off - Monday.

Tel: +7 (495) 692-44-59

Share with friends

Project presented by the National Fund of the Contemporary Art, Paris

For the press

A girl babbling to her doll or a boy playing with his cars express the necessity to apply their desires to something, to imitate the reality which for them is made up by their parents, to influence the world surrounding them. For that purpose they use something that an American psychoanalyst calls a «transitional object».

Photography as a magical and transitional object, following the paths of literature, visual and fine arts, gave an opportunity to many modern artists to dream about their possible past, express their anxiety, parody the absurdity of everyday life and try to change the course of things.

It is true that photography, forced for a long time to be content with the role of the «mirror of nature» or, in the words of William Henry Fox Talbot, to be «the pencil of nature», i.e. the only true opportunity to faithfully depict reality, little by little managed to enforce its provocative power over the imaginative.

Oscar Rejlander, an English artist of Swedish origin, was one of those who gave a start to some interesting polemic, when in 1857 he demonstrated to the public The Two Ways of Life, a collection of thirty photographs which represented a large-scale allegory of vice and virtue. It was highly praised by Queen Victoria, but attacked by critics, because the artist used a combination of several negatives.

Some were infuriated and alarmed by this ruse, while others saw here an opportunity to test their imagination. Rejlander explained his method in 1863 when he wrote a work titled «The Apology of Photographic Art». Since then the character of photography began to change: models were dressed in a particular way, stage-sets created, different technical adjustments used, including, at a much later date, computers. This evolution overjoyed Lewis Carroll, who exclaimed: «From now on photography as a creation of the spirit reduced the art of the novel to a level of somewhat mechanical work». Lewis Carroll was doubtless a talented amateur photographer and his pictures with little Alice Liddell, who served as a prototype for «Alice in Wonderland», must have given him a lot of inspiration for writing this book.

Later photographers, who worked under the influence of English Pre-Raphaelites or the followers of the Photo-Secession movement with their preference for Art Nouveau, would defend their right to express their feelings and emotions on film. This right usually meant creating genre scenes, often imitating fine art, and in this way pursuing the goal of art for art’s sake, as it was understood by Charles Baudelaire. In other words: «to create suggestive magic, containing at the same time the object and the subject, both the world outside the artist and the artist himself».

The Surrealist revolution was still more radical and gave the artist an instrument capable of not only expressing his feelings, but his image of the world. Photograms, solarization, collage, double exposure — all these are used to transform the essence of things and allow us, in the words of the American photographer Henry Hauls Smith, «to place the power of a descriptive illusion at the service of allusion». So now people were talking about how to express ideas, not simply how to describe what surrounds you.

In the late 70s, after a long period of photography’s triumphal march in the role of a documentary instrument for studying man, the world and the universe, a new generation of artists added to the many technical achievements of the medium different gadgets, figures, signs or models, thus staging their doubts, concerns or even whole fictitious autobiographies, in order to put a spell on their fears and create a more acceptable society.

It is evident that for them the vague and unpleasant laws of normal life are replaced in the space of the picture and in photographic time by clear, but arbitrary rules that they set for themselves. The game is to invent answers to burning questions, while knowing that at any moment one can close the shutter and leave the playground.

Often the autobiographical element is the main axis of their images. Thus we can see Tom Drakhos, who became famous with his reports, right after the Prague Spring and his emigration to France, creating a series of scenes, where one can see plastic figures, — some are wounded, maimed or have their mouths bandaged, a real symbol of their freedom gone.

Nevertheless inventing parallel lives gives an opportunity to feel oneself happy — like Morimura, entering the personage of Brigitte Bardot; or to imagine yourself being a hero among legendary stars — like Olivier Rebufa, creating a new Dolce Vita, without the trouble of analyzing the meaning of those fictitious moments of happiness, for which he drags a Barbie from one banal shot to another.

Like children, photographers unhesitatingly endow with magic the fairy-tales they tell to themselves, as well as the artifacts which are expected to revive society. This is how Joan Rabascall works: in his project entitled «My Collection» he demonstrates the triteness of TV shows by a series of images reproduced on toy screens, trying to convince us how an immoderate consumption of these pictures can only become something senseless and boring. In the same manner Abigail Lain describes with sober irony a crime scene in a detective movie, all the springs of which are known beforehand; or Pierre and Gilles in the series Washing Powder unmask the triviality of an ad.

We can also notice that some of the objects exist within the strange world of children’s literature: Gregory Krewdson meets Gulliver; while the silent adventures of things, told by Agnes Propeck, are reminiscent of the world of the Queen of Hearts, created by Lewis Carroll. These shots are not provocative. At other times authors joyfully jeer at the senselessness of things.

An artist, playing with creating an imaginary personality, «temporary forgets, decorates, undresses his individuality, pretending to be something else». The first element that is used for building a new image is, doubtless, a mask, symbolizing an intermediary object between the individual, on the one hand, and the divine, the supernatural, death, the unseen and other people, on the other. A person who puts on a mask wishes to stay nameless. This is why for security reasons Drakhos’ small figures are wearing masks; however the impossibility and the emptiness of the mask’s frozen expression make us believe, like Sugimoto, that masks are «fixed dreams». It was often noted that a mask hides the social qualities of man and opens up his true essence. The same things happen with the change of dress in the Michael Jackson series, created by Valeri Belin.

Nowadays imagining and pretending became constant notions in the dictionary of modern art because of the evolution of the photographing method. Freeing themselves from the technical limitations, connected with the process of shooting, artists found an aid in computer programs, which helped them liberate their imagination and construct real «imitations», as we see them in the Japanese scenes of Pascal Monteil or in the strange, but credible models of Ignez Lamsveerde. Apart from that, owing to the fact that photography escaped from the printed page and turned into a picture on a wall, artists began to borrow certain features of fine art and often, in creating their images, use the whole wealth of the preceding cultural tradition: such is the connection with art history of Bae or Balogh, movie images in Al Janabi and historical quotations in Sugimoto. Sometimes they parody the language of advertisements, as is the case of Pierre and Gilles, or replay scenes from everyday life, creating what is now called the «new documentary genre».

In other cases an artist carries on with the game of pretending to create a history of a personage, to whom he gives his own face; we see that in the works of Lauri Simmons, Teun Hocks, Abigail Lan or Morimura. The problem here is not only to build a small mise-en-scene, but to immerse into the world of imaginative autobiographies.

Only in this context and paying this price is it possible to influence the world in some way and to try to change it.

Agnès de Gouvion Saint-Cyr