Russia and Izvestia: 100 Years

Victor Akhlomov Urai, Ust-Balyk, Tyumen June 1961

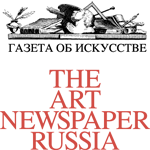

Victor Akhlomov Vladimir Vysotsky in the "Hamlet". December 1971

Victor Akhlomov Overlap of the Yenisei. Charles's point. Sayano-Shushenskaya HPP. October 11, 1975

Sergey Smirnov "Wash your own water." The withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan. 1989

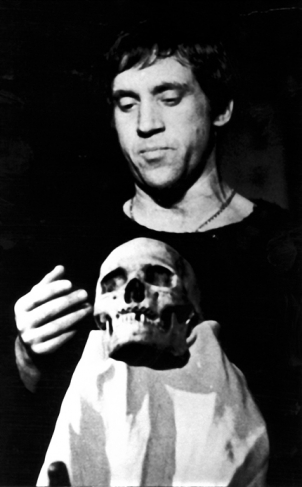

Victor Akhlomov The poetess Bella Akhmadulina. Moscow, the Luzhniki Stadium. 1973

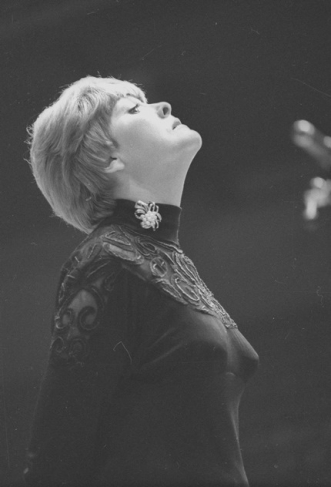

Victor Akhlomov Fidel Castro is a Cuban revolutionary and First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Nikita Khrushchev (from left to right) at the Bolshoi Theater. Moscow. May 1, 1963

Victor Akhlomov Kuznetsky Most metro station. Moscow. 1973

Pavel Troshkin. Short rest at the moment of calm

Nikolay Petrov Maxim Gorky on the roof of the building of Izvestia. Moscow. 1928

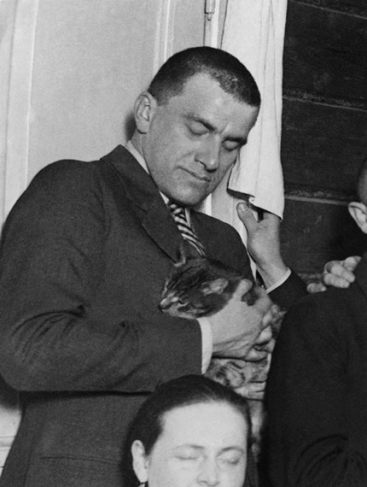

Nikolay Petrov Poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in the newspaper Izvestia. 1926-1927

Moscow, 6.04.2017—14.05.2017

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

This year the legendary national newspaper Izvestia celebrates its centenary. Izvestia is the mirror of an epoch, reflecting the most important, vivid and significant events in our political, economic, international and cultural life.

The project ‘Russia and Izvestia: 100 Years Together’ is a unique chronicle of the country.

The newspaper has changed with the country. And like the country, it has experienced difficult times and periods of prosperity.

Since its inception on 13 March 1917 the Izvestia newspaper has reported on the socio-political course of the era.

One of the first editors of the newspaper, Menshevik Fyodor Dan opened the 2nd All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies on 7 November 1917, at the very moment when storming of the Winter Palace began. The first decrees of Soviet power, ‘On Peace’ and ‘On Land’ were published in the pages of Izvestia.

An opponent of Dan and a Bolshevik, Izvestia editor Yuri Steklov authored the first Constitution of the USSR in 1924. Nikolai Bukharin, another Izvestia editor, wrote the text of the Constitution of 1936. Bukharin’s predecessor as editor Ivan Gronsky first coined the term ‘socialist realism’ and, with Maxim Gorky, became instrumental in establishing the Union of Soviet Writers.

The 1980s editor-in-chief Ivan Laptev sought a revolutionary decision by the Central Committee of the CPSU and the USSR Supreme Soviet to end the consideration of anonymous letters, and finally this practice of denunciation that had existed since the period of mass repressions was ended, thanks to Izvestia.

The Izvestia team were among those who suffered from the Stalinist terror in the 1930s. Six editors were repressed, not to mention dozens of rank-and-file employees. On 27 February 1937 Nikolai Bukharin was arrested in his office. A year later the newspaper published the last words of the

defendant Bukharin, who repented of ‘villainous crimes’ committed by the ‘Right-Trotskyist bloc’...

Alexei Adzhubei was editor-in-chief of the Thaw-era newspaper and the son-in-law and confidant of First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Nikita Khrushchev. He negotiated with Pope John XXIII in the Vatican about the possibility of concluding an agreement between the Soviet Union and the Vatican, and also discussed the mitigation of political and military confrontation with President John F. Kennedy. But even he finally lost his post and was banned from the profession for the next 25 years. Until the late 1980s he had no right to use his own name on articles or books.

It was under Alexei Adzhubei, who headed the newspaper from 1959, that Izvestia became the mouthpiece of democratic changes that began in the country after the 20th Congress of the CPSU, the Congress of De-Stalinisation.

Exclusive materials from the best journalists in Russia were published in Izvestia. Yuri Gagarin visited the editorial office on Pushkin Square in 1961, after returning to Moscow from his voyage into space. On the day after his flight Izvestia published a book about the first cosmonaut in an edition of 300,000.

Due to their special status Izvestia could implement journalistic projects that were impossible for any other newspaper of that period. Izvestia were innovators and leaders in the mass media, ideally providing just what the public required at that moment in time. They introduced the famous column ‘Letter that made us take to the road’ — journalistic investigations directed against the bureaucratic arbitrariness of officials. The Izvestia letters department turned into a unique project, with 27 public reception rooms operating in different regions of the country. Thanks to articles in Izvestia that reacted to the fate of every individual ‘little man’, thousands of people who had suffered unjustly were amnestied. The newspaper gained an unprecedented level of trust from their readers and print runs soared to a record 10 million. Queues formed for Izvestia and whole families subscribed to the newspaper.

For the first time in the history of the Soviet press Izvestia launched a Sunday supplement, Nedelya [The Week], created on the same principle as supplements to major European newspapers, with reviews, photographs, poetry and prose, drawings and cartoons. In different years, Izvestia published the best writers, poets, journalists and artists: Vladimir Mayakovsky, Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Zoshchenko, Alexander Tvardovsky, Konstantin Simonov, Vasily Shukshin, Valentin Rasputin, Andrei Voznesensky, Robert Rozhdestvensky and many others. Famous graphic artist and patriarch of Soviet caricature Boris Yefimov worked at Izvestia for 86 years. The exposition includes a newspaper from 1922 that published his first cartoon, and work he created specifically for the publication.

The exhibition presents unique documents from the archive of the special department that remained ‘classified’: confidential correspondence with Stalin and the Party Central Committee, with heads of the People’s Commissariats and ministries or special correspondents of the newspaper abroad, as well as artefacts such as Nikolai Bukharin’s typewriter, the 1940 editorial identity card of outstanding photographer Mikhail Prekhner who worked at Izvestia until his death in August 1941, and other items.

Naturally the most important part of this exhibition is the photographs. Since its inception Izvestia has been famous for having one of the strongest photographic departments in the country. Photo correspondents from the newspaper created a unique chronicle of the war years and the work of Dmitri Baltermants, Samari Gurari, Georgi Zelma, Georgi Samsonov and Pavel Troshkin are now known and recognised worldwide.

Regular Izvestia photojournalists Konstantin Kuznetsov, Anatoly Skurikhin, Nikolai Petrov, Sergei Smirnov, Alexander Steshanov and Viktor Akhlomov are among those who inscribed the most important pages in the country’s photo chronicle.

The exposition includes both original issues of Izvestia, including the years 1917 to 1918, and reprints of different issues of the newspaper from the 100 years of its existence, as well as typographical stereotypes with the first documents produced by the Soviet government, the Decree on Peace and the Decree on Land.

Also shown at the museum are fragments of documentary films about the work of the editorial staff, including footage from the 1924 film ‘Microbe of Communism’, which describes the process of creating the newspaper 90 years ago.

Visitors to MAMM have the opportunity not only to study Izvestia’s archive files, but also to read the latest issues of the newspaper, which will be supplied daily from the printing house throughout the duration of the exhibition.

General information partner

General radio partners |

Strategic information partners |

Special media partner

Information partners