Presented by the Artist

Mexican photographer Alinka Echeverria, photographed Catholic pilgrims on the road to the sacred site of Tepeyac in 2010, the year her countrymen celebrated the 200th anniversary of independence and the centenary of the Mexican Revolution. Each year in mid-December six million people flock to the Basilica de Guadalupe to receive the blessing of the ’brown skinned virgin’, protector, ultimate mother and goddess.

Details

Presented by the Artist

Mexican photographer Alinka Echeverria, photographed Catholic pilgrims on the road to the sacred site of Tepeyac in 2010, the year her countrymen celebrated the 200th anniversary of independence and the centenary of the Mexican Revolution. Each year in mid-December six million people flock to the Basilica de Guadalupe to receive the blessing of the ’brown skinned virgin’, protector, ultimate mother and goddess.

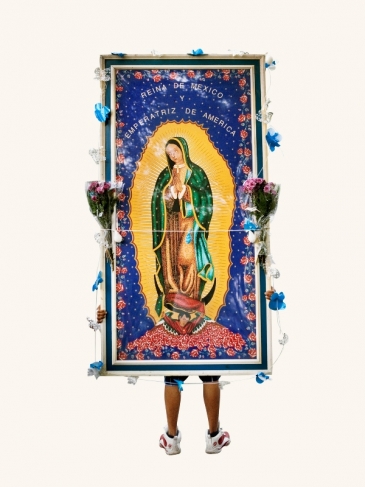

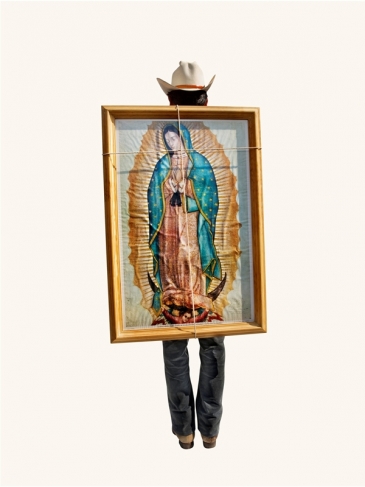

The story of this sacred emblem of the Virgin of Guadalupe dates back to 1531, when she appeared several times to the indigenous man Juan Diego and asked him to build a church at the spot where the temple of Aztec goddess Tonantzin once stood. At first, the local bishop remained sceptical and demanded proof. Thereupon, the Virgin Mary told Juan Diego to cut down roses that had unexpectedly bloomed on the hilltop in mid-winter and take them under his poncho to the bishop. An imprint of the Virgin Mary appeared on the fabric as a holy image surrounded by rays of light. When the bishop authenticated the peasant’s story a basilica was built and subsequently became one of the most frequently visited Catholic churches in the world, due to this image not-made-by-human-hands.

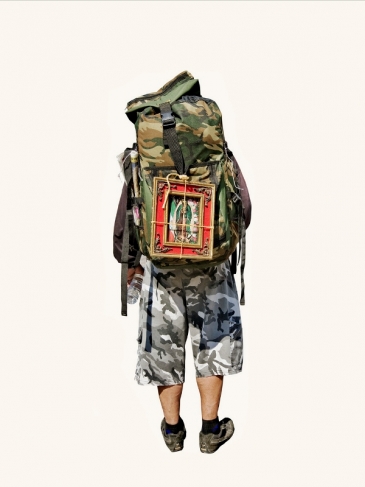

Alinka Echeverria (b. 1981), a graduate of the International Center of Photography in New York, studied social anthropology in Edinburgh and visual anthropology in Bologna before being invited to shoot a documentary film about the Basilica of the Lady of Guadalupe as part of an Italian film crew. There she saw the icon of the Virgin on one of the pilgrim’s backs, she appeared to be dancing between street traders, policemen and paramedics. It was then she devised the idea for her project — to collect and juxtapose the numerous images of the Holy Virgin carried on the backs of pilgrims. A year later she returned to Tepeyac and photographed rear views of people weighed down with pictures, sculptures and painted fabrics a hundred meters from the Virgin of Guadeloupe Basilica, from 6 am to sunset. Many of her subjects were unaware of the photographer — she was unwilling to interfere in their devotions and many refused to face the camera after their long and arduous journey. Of the 6 to 8 million pilgrims about half bear a heavy burden — domestic interpretations of the original image they brought to the shrine for blessing. The pilgrims walk for up to ten days, pay homage to the Virgin on the anniversary of her apparition and sleep in the square until 5 am the next morning, when they congratulate the Virgin on her ’birthday’.

Among the photographers that have influenced Alinka, she cites August Sander and his philosophy of recording the ’Face of our Time’, also Bernd and Hilla Becher with their method of systematic documentation. At the same time Alinka Echeverria fills her project with ideas of a specific place, collective memory, folk religion, everyday kitsch, ritual and identity, while still retaining the concept of miracles and experience of spiritual practice. Her project is at the juncture between anthropology, conceptual art and journalistic research, presenting the viewer with a new genre form — the conceptual documentary. Alinka Echeverria was resident photographer at the Arles National School of Photography (2010-2011), a prizewinner of the HSBC award for photography (2011) and participant in World Press Photo’s Joop Swart Masterclass (2011).

Close