Revolution in Photography

Alexander Rodchenko. Stairs. 1930. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodtschenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Fire Escape (with a man). From the series “House in Miasnitskaya St”. 1925. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodtschenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

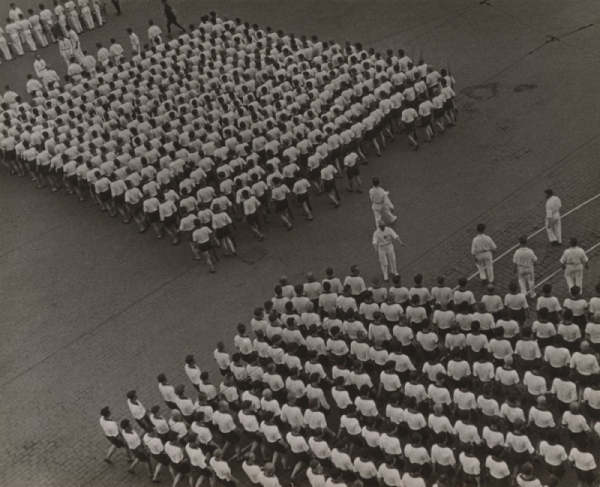

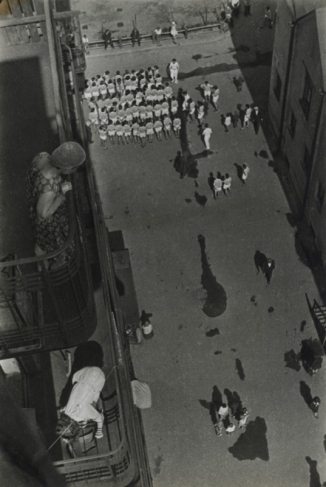

Alexander Rodchenko. Column of the Dynamo Sports Society. 1932 (1935). Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodtschenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

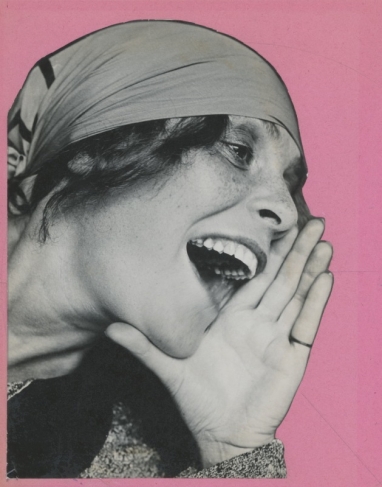

Alexander Rodchenko. Lily Brik. Portrait for the Poster “Knigi”. 1924. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Guard near Shukhov Tower. 1929. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodtschenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Girls with Kerchiefs. 1935. Vintage Print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Pioneer- trumpeter. 1930. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

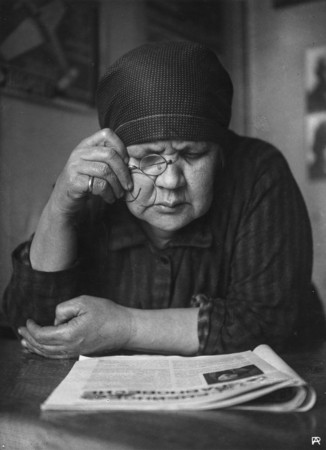

Alexander Rodchenko. Portrait of the Artist’s Mother. 1924. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Poet Vladimir Mayakovsky. 1924. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Races. 1935. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Girl with a Leica. 1934. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. People Gathering to Take Part in a Demonstration. 1928 (1933). Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

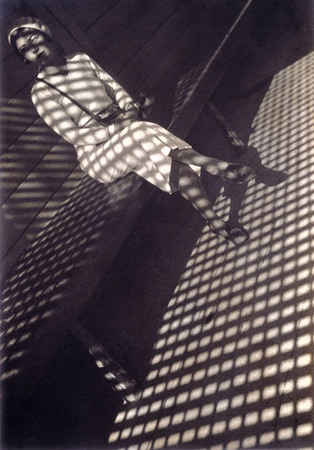

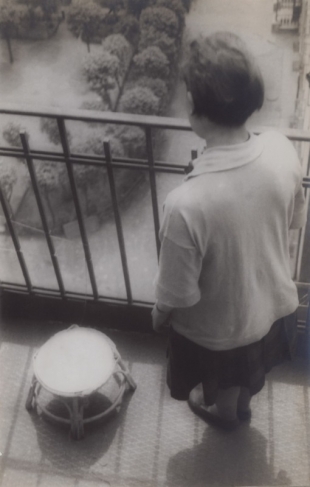

Alexander Rodchenko. Stepanova on the balcony. 1928. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Radio-listener. 1929, Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Cover of the book “About That” by Vladimir Mayakovski. 1923. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Balconies. Corner of a House. 1925. Vintage Print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

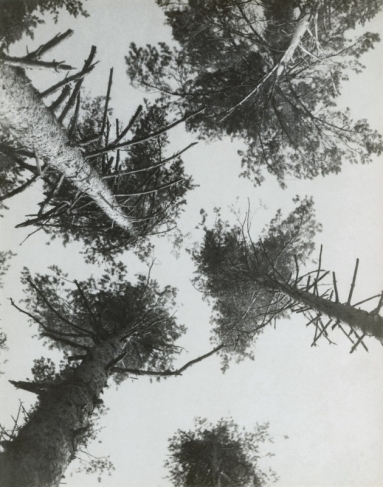

Alexander Rodchenko. Pine-trees. Pushkino. 1927. Vintage Print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Pioneer Girl. 1930. Vintage Print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

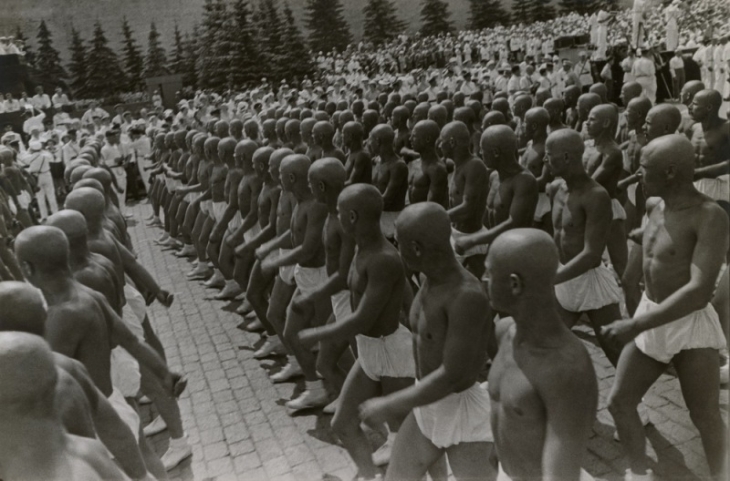

Alexander Rodchenko. Sportsmen in Red Square. 1935. Vintage Print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko and Warwara Stepanowa. Young Gliders. Sketch of a double page for the magazine “USSR in Construction”. 1933. Cardboard, photomontage. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Nizhniy Novgorod, 24.01—16.03.2025

exhibition is over

Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum

Minin and Pozharsky Square, 2/2

Share with friends

Curator: Olga Sviblova

Exhibition shedule

-

7.02.2008—27.04.2008

London

Hayward Gallery

-

12.09.2008—18.08.2009

Berlin

The Gropius Bau

-

14.11.2009—6.02.2010

Amsterdam

FOAM — Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam

-

14.11.2009—6.02.2010

Rio de Janeiro

Instituto Moreira Salles

-

10.10.2010—8.01.2011

Sao Paolo

Pinacoteca Sao Paolo

-

28.05.2011—15.09.2011

Moscow

Winterthur Fotomuseum

-

10.10.2011—8.01.2012

Rome

Palazzo delle Esposizioni

-

10.10.2011—8.01.2012

Krakow

National Museum Krakow

-

22.05.2012—19.08.2012

Vienna

WestLicht. Schauplatz für Fotografie

-

11.06.2013—25.08.2013

Reykjavik

Reykjavik Art Museum

-

5.10.2013—12.01.2014

Mantova

Palazzo Te

-

27.02.2016—8.05.2016

Lugano

Museo d’Arte al LAC

-

29.03.2018—27.05.2018

Palermo

Real Albergo dei Poveri

-

18.06.2018—23.09.2018

Senigallia

Palazzetto Baviera

-

26.10.2018—20.01.2019

Zagreb

Museum of Arts and Crafts, Zagreb, Croatia

-

24.01—16.03.2025

Nizhniy Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum

For the press

Alexander Mikhailovich Rodchenko

The Moscow House of Photography has been setting up annual exhibitions of Alexander Rodchenko’s oeuvre for the last ten years. Specialist of the museum conducted some thorough research of the master’s archive, and it took them four years just to scan all the negatives. In 2004 the Moscow House of Photography gave an award to Rodchenko for his outstanding contribution to world art — in his lifetime he never received a single award. It was handed over to his heirs, a wonderful family, which works as a single research institute and which largely helped the public to form an adequate overall picture of Russian photography that had appeared in the 1920s-40s. The heirs decided that they will spent the money on a monograph about Alexander Rodchenko, which will be officially presented at the exhibition’s opening.

Russian 20th-century Avant-Garde is a unique phenomenon not only for Russia, but for the world as a whole. The dazzling creative energy, displayed by the masters of this great epoch, still inspires contemporary art and every one of us when we look at the works that appeared in the age of Russian Modernism. Alexander Rodchenko was doubtless one of the major aesthetic innovators of the time who deeply influenced the spirit of the era. Painting, design, theatre, cinema, printing, photography... — all these spheres in which the powerful talent of this very beautiful and strong man manifested itself were transformed, opening up completely new ways of development.

The early 1920s was an «interval period», as Victor Shklovski, one of the best critics and theorists of the era, termed it. It was a moment when, even if in reality it was just a short-lived illusion, a certain resonance emerged between aesthetic and social experiments. This was precisely the time when in 1924 Alexander Rodchenko, an already mature and famous artist who made the corner-stone of his aesthetic the slogan «we have to experiment», turns to photography. The results were not just the masterpieces he created, that are now classics of Russian and world photography, but the changes in the way people perceived photography and the role of the photographer. A mentality of design was introduced into this sphere, so that photography became not only a reflection of reality, but a medium for visually representing dynamic constructions of the mind.

Rodchenko brought into photography the ideology of Constructivism, worked out the method and the instruments for its realization. The technique he discovered was instantly repeated by others. Not only his disciples and associates turned to it, but also his aesthetic and political opponents. However, just using «Rodchenko’s method» by itself, like the diagonal composition he invented or other innovations, did not automatically guarantee the high artistic quality of the shot. The achievements of Rodchenko-photographer were based not so much on formal issues, for which he began to be severely criticized in the late 1920s, but on a deep, inner romanticism which was his characteristic feature since he was a student (take, for example, his wonderful letters-fairy tales which he wrote to Varvara Stepanova in the early years of their acquaintance).

This romantic trait, going back to his childhood which was spent backstage (his father worked in a theater), evolved into a powerful utopian vision of Rodchenko-Constructivist, who truly believed in the possibility of positively transforming the world and the human being. In the 1920s Rodchenko sets new tasks for each consecutive photo series and creates manifestos about how photography and life should change, remodeled by creative Constructivism. In the 1930s, particularly at the end of the decade, persecuted and criticized, he tries to analyze both life and art, including his own oeuvre, its evolution largely determining the future aesthetic of Socialist Realism. Incidentally, among Russian photographers of the first half of the 20th century Alexander Rodchenko is a unique case — owing to his articles and diaries we have an outstanding insight into the mind of a photographer-thinker, whose work was guided by a specific aesthetic program.

Tired of constant revolutionary changes that created a reality far from the ideals that inspired his early works, Rodchenko wrote in his diary on 12 February 1943: «Art is serving the people, but the people are being led in different directions. What I want is to lead the people to art, not to lead someplace with the help of art. Am I born too early or too late? We must separate art from politics...».

In his latter years Alexander Rodchenko was betrayed by friends and followers, persecuted by the authorities, deprived of the opportunity to work and make a living, of participating in exhibitions, he was also expelled from the Union of Artists and suffered from a serious illness. But he was lucky. He had his family: his wife, friend and associate Varvara Stepanova, his daughter Varvara Rodchenko and her husband Nikolai Lavrentiev, their son Alexander Lavrentiev and his family. It was a small but very closely united clan charged with creative energy. Just like it was for Alexander Rodchenko to create became the essence of their lives. And they also devoted their lives to preserving the heritage of Alexander Rodchenko and to serving photography. Owing to their efforts Rodchenko’s oeuvre was recognized anew by the world and by his homeland.

If it was not for this family, it is possible that the first photographic museum in Russia —"Moscow House of Photography« — may have never appeared. In Rodchenko’s house, together with his family, we discovered and studied the history of Russian photography, which it is hard to imagine without Alexander Rodchenko.

Olga Sviblova, Director of the Museum «Moscow House of Photography»

Olga Sviblova

Generator of Art

The Russian avant-garde of the twentieth century is a unique phenomenon not only in Russian, but in world culture. The amazing creative energy accumulated by the artists of this great age is still providing nourishment for artistic culture today and all who have dealings with the art produced by Russian Art Nouveau. Alexander Rodchenko was indisputably one of the main generators of creative ideas and the general spiritual aura of the age. Painting, design, theatre, cinema, typography and photography, all areas invaded by the powerful talent of this strong, handsome man, were transformed, opening up radically new paths of development.

The early 1920s was an «intermediate age», to quote Viktor Shklovsky, one of the finest critics and theoreticians of the day, a period when, albeit briefly, illusively, there was a resonance between artistic and social experiment. It was at this time, 1924, that photography was invaded by Alexander Rodchenko, already a well-known artist with the slogan «Our duty is to experiment» placed firmly at the centre of his aesthetic. The result of this invasion was a fundamental change of ideas about the nature of photography and the role of the photographer. Conceptual thinking was introduced into photography. Instead of just being the reflection of reality, photography also became a device for the visual representation of dynamic intellectual constructions.

Rodchenko introduced Constructivist ideology into photography and developed methods and instruments for applying it. The devices discovered by him spread rapidly. They were used by pupils and like-minded practitioners, as well as aesthetic and political adversaries. The use of the «Rodchenko method», which included the diagonal composition, discovered by him, as well as foreshortening and other devices, did not automatically guarantee the artistic dimension of a work, however. The practice of Rodchenko the photographer was confused not only and not so much by the formal devices for which he was so mercilessly criticised in the late twenties, as by the profound inner romanticism characteristic of him even in his student years. Suffice it to recall the make-believe letters he wrote to Varvara Stepanova in the early years after they met. This romantic element, embedded in the childhood which he spent back-stage in the theatre where his father worked, was transformed into the powerful utopian thinking of Rodchenko the Constructivist, who believed in the possibility of a positive transfiguration of the world and mankind.

In the 1920s in each new photographic series Rodchenko set new tasks and produced manifestoes on what photography and life would be like after they had been transformed by the Constructivist artistic principle. In the 1930s, particularly towards the end, exhausted by criticism and persecution, he tried to analyse life and artistic practice, his own included, the evolution of which was determined largely by the developing aesthetics of socialist realism. Incidentally, in the whole history of Russian photography of the first half of the twentieth century Alexander Rodchenko is the only person who, thanks to his printed articles and diaries, left unique records, artistic reflections by a photographer-thinker who witnessed historical cataclysms, which generated within him a tragic conflict of conscious premises and the unconscious drive to create.

Tired of the constant revolutionary transformations that produced a reality far from the ideals which had inspired his early period of creativity, he wrote in his diary on 12 February 1943: «Art is service of the people, but the people are being led goodness knows where. I want to lead the people to art, not use art to lead them somewhere. Was I born too early or too late? Art must be separate from politics ...»

In the final years of his life, betrayed by friends and pupils, deprived of the right to work and earn his living or take part in exhibitions, expelled from the Union of Artists, and in very poor health, Alexander Rodchenko was nevertheless a very fortunate man. He had a family: his friend and comrade-in-arms Varvara Stepanova, his daughter Varvara Rodchenko, her husband Nikolai Lavrentiev, his grandson Alexander Lavrentiev and his family, a small, but very close-knit clan charged with creative energy. If it had not been for this family Russia’s first photographic museum, the Moscow House of Photography, might never have appeared. In Rodchenko’s house, together with the Rodchenko family, we have discovered and studied the history of Russian photography, which would be unthinkable without Alexander Mikhailovich Rodchenko.