Reportages

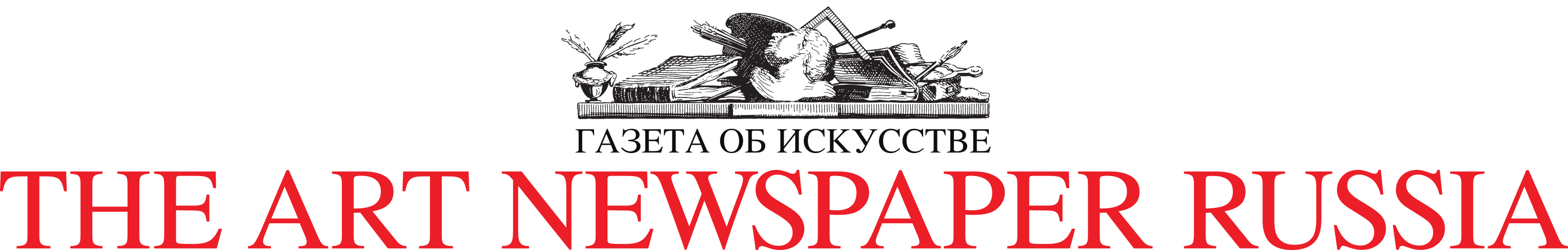

Pascal Maitre. Afghanistan, 1992. Kabul. In the mosque of Chindawol, women stand in the area specially reserved for them, waiting for prayer to begin. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. USA, 2018. Memphis. Rock concert in a former brothel where women died from yellow fever. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Eritrea, 1992. A man, lost in thought, in a bar with clear Italian influence at Asmara. Maybe he does not yet realise that the long war for independence is over. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Niger, 1993. Fighters of the Tuareg Rebellion. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Mali, 2019. Dozo traditional hunters from the Bambara people have been drafted into a militia. They are assisted and supported by the Malian government, which makes them fight against the Fula people, who have joined the Islamists. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Congo, 2012. The fashionable Sapeurs (a French acronym for the “Society of Atmosphere-makers and Persons of Elegance”) of the Léopards du Congo group in the Matonge neighbourhood. They wear second-hand clothes by leading designers such as Yamamoto, Dolce & Gabbana, and Paul Smith. The Sape fashion statement first appeared in the late 1970s as a reaction to the ‘authenticity’ advocated by Mobutu, who banned western-style clothing. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Niger, 1996. Wodaabe women struggling against a sand storm in the plain of Azawak. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

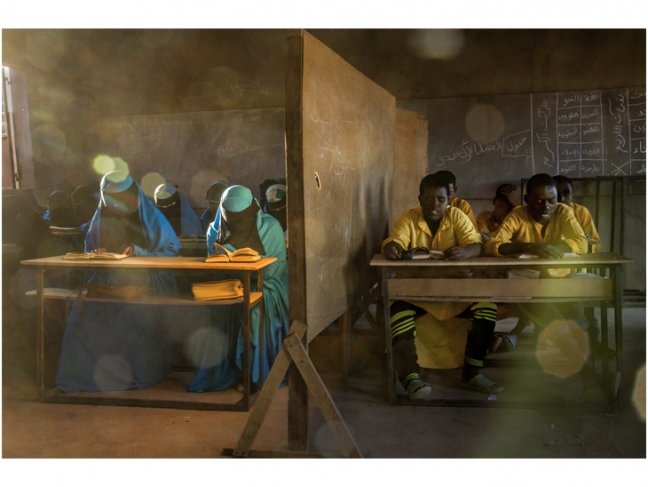

Pascal Maitre. Niger, 2018. Izala Islamic school at Agadez. The Izala reform movement advocates a return to the foundations and the use of conservative practices. The movement is historically connected with Boko Haram founder Mohamed Yusuf. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Madagascar, 2016. Manarintsoa is a poor neighbourhood of Antananarivo with no street lighting. Here, a street vendor is selling hot dishes. It is difficult to survive in the capital, one of the poorest cities in the world. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Chad, 2015. The village of Ngouboua on Lake Chad was the target of Boko Haram’s first attack in Chad. On February 13, 2015, 46 armed men in four dugouts with outboard motors ambushed the village at 3 o’clock in the morning, targeting and killing the district officer and setting fire to many of the homes. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos

Pascal Maitre. Niger, 2007. A migrants’ truck in the Tenere Desert. Thousands of people, mostly from Nigeria, Ghana and Mali, cross the daunting desert hoping to find work in Libya or to reach Europe. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Pascal Maitre. Congo, 2012. In 1914, the Belgians set up the Binga palm oil processing plant. In 1999, everything was looted during the Congolese Civil War, and the Belgians left, abandoning their plantations covering 16,000 hectares or 40,000 acres and a total of four industrial plants for processing palm oil, rubber, coffee and cocoa. Everything was bought up by Mr. Blattner, GBE Group CEO. When we eat a well-known hazelnut chocolate spread or use cosmetics containing palm oil, we are no doubt unaware of the working conditions of labourers in the palm oil industry. © Pascal Maitre/Myop/Panos.

Moscow, 22.01.2021—23.04.2021

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

XIII INTERNATIONAL MONTH OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN MOSCOW ‘PHOTOBIENNALE-2020’

Exhibition organised with the participation of Le Figaro Magazine

Curators: Anna Zaitseva, Cyril Drouhet

As part of the ‘Photobiennale-2020’ the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow presents an exhibition by celebrated French documentary photographer Pascal Maitre.

Pascal Maitre was born in 1955 in Buzançais (France), to the family of a blacksmith. He was given his first camera, a Rolleiflex 4×4, by an aunt who married an American soldier and lived in the northern USA. After leaving school Maitre studied psychology at university and was then drafted into the army, where he served in a photography unit. There he developed a serious interest in photography, and in 1979 he started work for the magazine ‘Jeune Afrique’ as a photojournalist. This began a photographic journey that lasted four decades, first deep into the African continent, and later across the countries of Africa, South America, Asia, the Middle East and Europe.

Pascal Maitre has collaborated with the world’s most famous periodicals: ‘Le Figaro Magazine’, ‘Geo’, ‘L’Express’ and ‘Paris Match’ in France; ‘Geo’, ‘Stern’ and ‘Brigitte’ in Germany; ‘National Geographic’ in the US. He has published a number of books for major publishing houses and won several prestigious photojournalism awards. In 1987 he received the World Press Photo prize for his photo reportage on participants in the Mexican revolution.

Many of Pascal Maitre’s works resemble paintings, although the photographer never takes staged shots and each of his images is a document. Maitre has worked in major hotspots worldwide, telling his audience about the life, culture and traditions of different peoples, as well as revealing the causes of bloody wars and the basis of international political conflicts. Pascal Maitre’s pictures are surprisingly cinematographic and all his series uncover an exciting real story.

The photographer describes his work with his usual modesty: ‘Generally speaking my profession is simple. Perhaps the most difficult part is getting there. To be physically present in places where something interesting is happening. Once I’m there, it’s not so hard to press the shutter.’

Pascal Maitre never uses a digital camera, as a matter of principle. On average he shoots five films per day. Often he selects just two or three of the best photos from each reportage for inclusion in a book or exhibition. The remainder become illustrations for texts issued in the media.

Friends of the photographer remark on his unique serenity, Maitre’s ability to ‘calm even the most agitated’ people he encountered in zones of military conflict, as well as the specific ‘panoramic’ vision that determines the quality of his pictures.

Pascal Maitre has always been lucky. In Africa many tribes still live in a primitive communal system and they are often wary of anyone with a camera, seeing it as a weapon. Some of their priests still believe a photographic image takes something from the person’s soul. But the photographer has always managed to agree on his shoots and produce the most reliable photo reportages. He has never been arrested. The world press keenly follows his exploits, and Maitre’s exhibitions have always brought great success at prestigious international venues such as the European House of Photography (France), the Visa Pour l’Image Festival in Perpignan (France), etc.