Polaroids

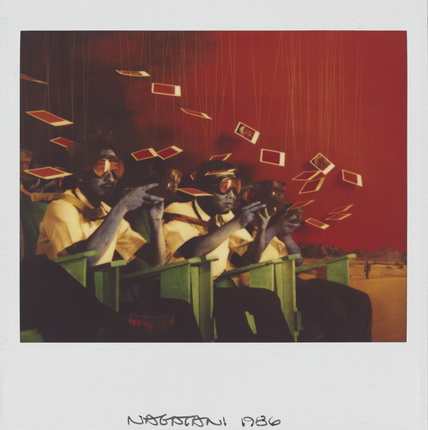

Patrick Nagatani. Cinema II, detail from the image: Alamogordo blues. 1986, Polaroid Spectra. © Patrick Nagatani

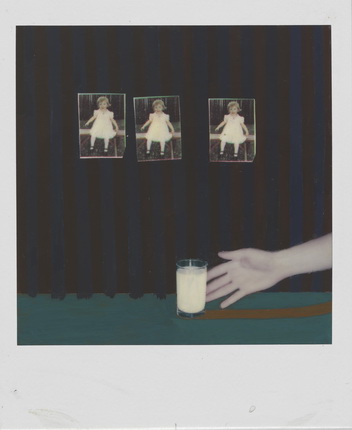

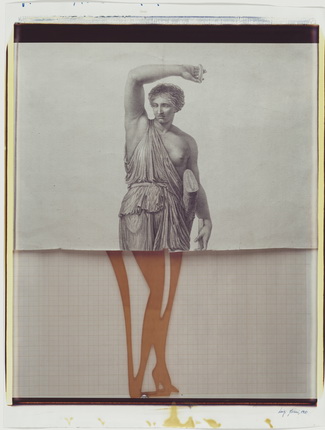

Bruce Charlesworth. Untitled. 1979, Polaroid SX-70. Hand-colored. © Bruce Charlesworth

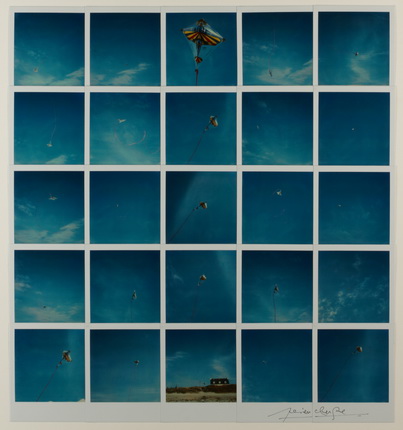

Lucien Clergue. Le Cerf Volant, Bretagne. 1984, Polaroid SX-70 Time Zero. © Lucien Clergue

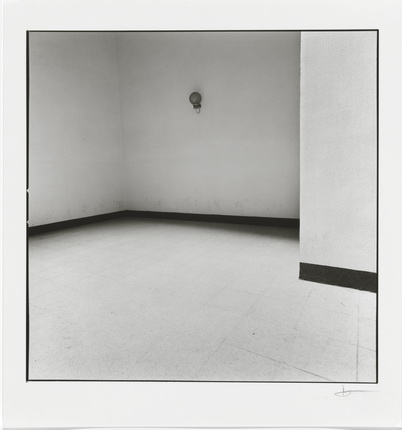

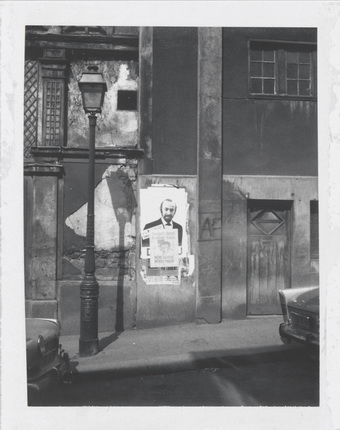

Joan Fontcuberta. Untitled. 1981 Polaroid Type 665. Gelatin silver print 10.4 x 10.4''. © Joan Fontcuberta / VBK Wien, 2011

Luigi Ghirri. AMSTERDAM. 1980, Polaroid Polacolor. 20 x 24''. © Eredi di Luigi Ghirri

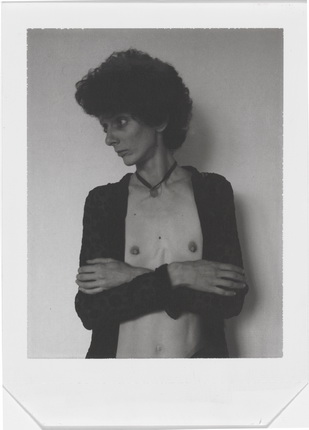

Robert Mapplethorpe. Untitled (Diane). ca. 1974, Polaroid Type 55. 4 x 5". © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation

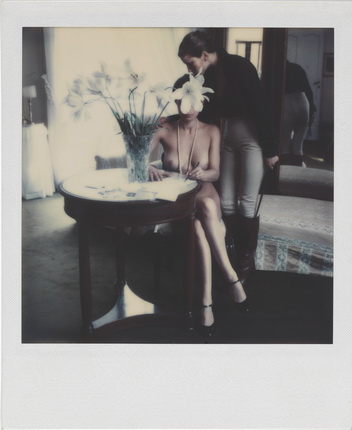

Helmut Newton. Untitled. 1976, Polaroid SX-70. © Helmut Newton Estate

Vicki Lee Ragan. The Princess and the Frogs. 1983, Polaroid Polacolor. 20 x 24". © Vicki Lee Ragan

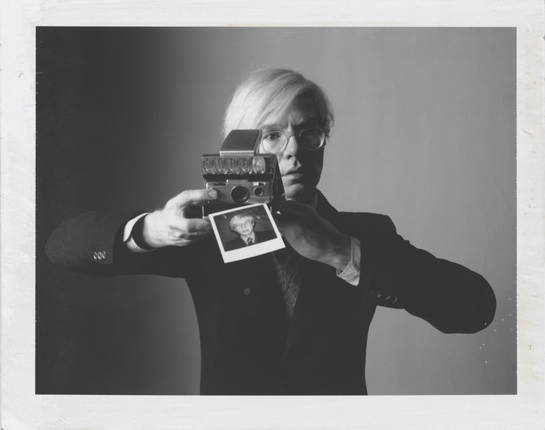

Oliviero Toscani. Andy Warhol with camera. 1974, Polaroid Type 105. 3¼ x 4¼". © Oliviero Toscani

Ulay. Untitled. 1969, Polaroid Type 665. 3¼ x 4¼". © Frank Uwe Laysiepen /VBK, Wien 2011

Andy Warhol. ANDY SNEEZING. 1978 Polaroid SX-70. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. / VBK, Wien 2011

Moscow, 25.04.2014—25.05.2014

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curators: Rebekka Reuter, Ekaterina Inozemtseva

For the press

For the first time in Russia MAMM presents a large-scale exhibition of photographs created using the technology of the so-called ‘one-step process’, the instant photograph or Polaroid (not the first time the name of a production company has been applied to an entire process, the method of photography and the product).

Most of this collection of Polaroids from the early 1960s to 1990s found a new home in Europe in 2011, in Vienna’s Westlicht Museum. This event is hard to overestimate, not only because of the quantity (about 4400 Polaroids are preserved in Vienna), but above all the quality, since the collection contains Polaroid photographs by Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, Ansel Adams, Robert Mapplethorpe, Paul Huf, Helmut Newton and others. All these famous names feature in the Moscow exhibition.

The ‘Polaroids’ project portrays a medium that almost vanished and then reappeared, not only as a resource that became indispensable in artists’ studios and the workplaces of photo editors, doctors and scientists, but also as a form of photography in its own right, offering new features and extended opportunities. Quite large prints could be produced using Polaroid cameras (visitors can see, for example, Polaroids measuring 20×24 in./50.8×60.96 cm.), and the instant development corresponded to the principal of this art form, making it possible to capture a fleeting moment, a minimal unit of time. The option to shoot a sequence and create something akin to animation attracted, for instance, Andy Warhol, who was always keen for novelty (the series ‘Andy Sneezing’), while in Mapplethorpe’s work, on the contrary, the subjects of his Polaroids stay static, ‘long-lasting’ and physically solid — for them microdynamics remains an alien concept. In general there is no hiding the fact that when you look at Polaroids by great photographers it is not immediately apparent, if at all, where the difference lies between their customary photographic process and shots taken with a Polaroid camera: Stephen Shore continues to focus on American landscape scenes and interiors, Huf is still fascinated by geometric volume and William Wegman photographs his Weimaraners, come what may. Although some specificity can be found here: the enhanced co-ordination of the composition yet at the same time a certain laxity and unreliability, a move towards serial thinking and the production of a whole sequence of photographic images, the fraught search for a subject — it seems the artists and photographers were striving to adjust to a new technology. The lifespan of this technology turned out to be very brief, therefore it is even more important to regard these Polaroid experiments by great photographers as unique objects, artefacts produced by an (almost) extinct technology.