Novokuznetsk Photo School: Nikolai Bakharev, Vladimir Vorobyov, Vladimir Sokolaev

Vladimir Sokolaev. ‘Happiness’. Obnorsky Street. Novokuznetsk. 1 May 1983

Vladimir Vorobyov. Helicopter with ‘Pravda’. Novokuznetsk. 1982

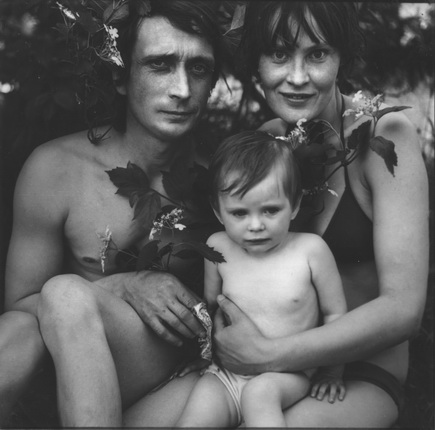

Nikolai Bakharev. From the ‘Relationship’ cycle. Novokuznetsk. 1988-1993. MAMM/MDF collection

Nikolai Bakharev. From the ‘Relationship’ cycle. Novokuznetsk. 1988-1993. MAMM/MDF collection

Vladimir Vorobyov. Overhead view. Meat trading row at Central Market. Novokuznetsk. 1981

Vladimir Vorobyov. Dismantling an entranceway canopy. Mezhdurechensk. 1981

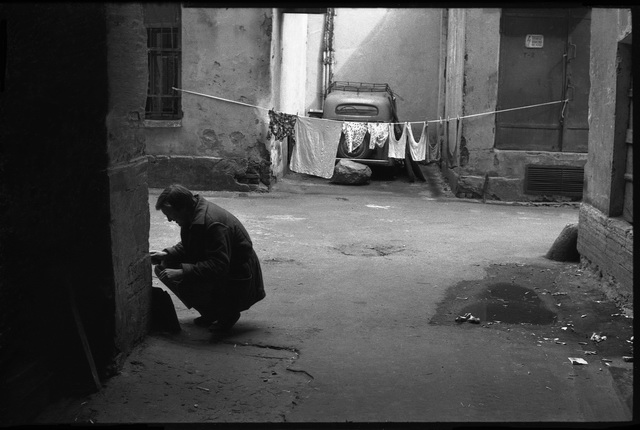

Vladimir Sokolaev. Garage made by laundry in a Nevsky Prospekt courtyard. Leningrad. 24 June 1982

Vladimir Vorobyov. Young father with friend outside Maternity Hospital No.1. Novokuznetsk. 1981

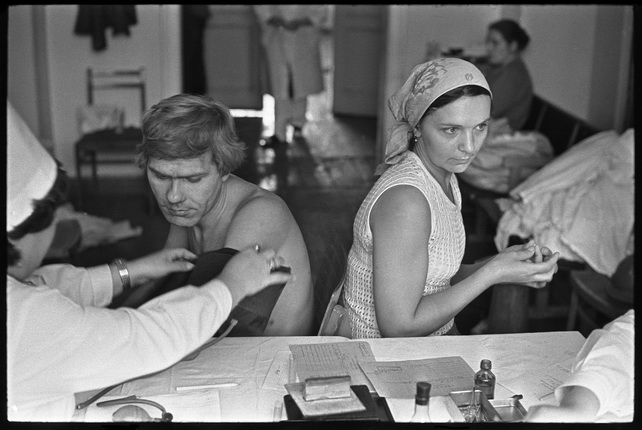

Vladimir Sokolaev. Donor’s Day at Kuznetsk Metallurgical Combine Novokuznetsk. 16 September 1981

Vladimir Sokolaev. Ambulance. Trying to save a suicide at Pokryshkina street. Novokuznetsk. May 1978

Share with friends

Curators: Olga Sviblova, Anna Zaitseva

Exhibition shedule

-

11.03.2016—9.05.2016

Moscow

Multimedia Art Museum

-

15.07.2016—23.10.2016

Yekaterinburg

Yeltsin–Center

For the press

This exhibition continues a series of MAMM projects devoted to the history of Russian photography and the history of Russia in photography. Although united by the umbrella term ‘school’, it represents Novokuznetsk photographers whose aims were diametrically opposed, both in terms of worldview and aesthetics.

Nikolai Bakharev is one of the most important and enigmatic figures in Russian photography of the late 20th century. A provincial custom-portrait photographer, from the early 1990s he became an acclaimed artist in Russia and abroad. His work is featured in group and solo exhibitions, as well as museum and private collections; his images were included in the main programme of the 55th Venice Biennale, and at the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d’Arles in 2013.

Born in the village of Mikhailovka in the Altai region in 1946, Nikolai Bakharev lost his parents at an early age and grew up in a children’s home. He began his working life at the Kuznetsk Metallurgical Combine (KMC), where Vorobyov and Sokolaev worked as staff photographers from the 1970s to early 1980s. In 1970, at the age of 24, Bakharev was employed as a professional photographer in a service centre, and the ‘custom photography’ format became the determining individual aesthetic for him. Images made to order had to satisfy the customer, so Bakharev carefully arranged the composition and poses, capturing his subjects at moments of happiness and maximum self-expression.

The ‘Relationship’ cycle was photographed on Novokuznetsk beaches in the late 1980s to early 1990s, when the customary Soviet way of life fell apart and photographers were obliged to seek clients on an individual basis. In particular they worked on beaches, taking souvenir snaps for vacationers. Bakharev’s photographs, at first sight the usual ‘beach shots’, have become classics of Russian photography, the portrait of a historical era at the moment of disintegration. As holidaymakers cast off their clothes they also abandoned the social determinacy of Soviet citizens who were raised to live as cogs in a system that neutralised individuality, including gender differences, to the utmost degree. These undressed people posing for a street photographer spontaneously show their desire for togetherness. Naturally enough, the majority are group portraits.

Bakharev’s artistic technique requires the photographer to be aesthetically distanced from his subject yet fully engaged in creating the composition. This tactic was wholly atypical for Soviet photography of that period. It could be said that Bakharev photographs his subjects in the aesthetics of naïve art or art brut, reducing to the minimum his authorial intrusion, which remains offstage appears only at the moment of staging, of setting the mechanisms for self-presentation by his characters.

With regard to outlook and aesthetic position Vladimir Sokolaev and Vladimir Vorobyov were opposed to the very idea of ‘custom photography’ and even worked as staff photographers at a major Soviet metallurgical plant, a classified facility — the Kuznetsk Metallurgical Combine. They show an affinity to photographic developments that originated among amateur enthusiasts spurred by Khrushchev’s Thaw of the late 1950s to early 1960s. Here the individuality and inner world of a particular subject are the primary focus, and this trend was apposite to the canons of Socialist Realism that unified individuals to the point of social generality — the Soviet people.

In 1978 Vorobyov, Sokolaev and Alexander Trofimov formed the TRIVA association for creative photography, which was officially registered two years later and became the first creative group of photographers registered in the USSR.

Back in the 1960s the Ministry of Black Metallurgy issued a decree for the organisation of film and photo studios at all major plants to record ideologically sound, high-quality materials about the production process. One of these studios, KMC-Film, appeared at the Kuznetsk Metallurgical Combine. This mighty film and photo centre that provided all the essential lighting and shooting equipment, reactants and photographic paper became a base for the TRIVA group’s activities. Group participants took photographs on the site of this massive classified plant to which other photographers were usually denied access. They were the first group to hold street exhibitions, on factory information stands in the city. During their one year of existence the group participated in 19 exhibitions, some of them abroad.

However, one year after their registration the group was disbanded by a resolution of the CPSU Kemerovo Oblast Committee, ‘for distributing ideologically harmful photographs’. This was the official reaction when the photographers attempted to send images to Amsterdam, to the World Press Photo Contest. In 1982 all the TRIVA participants were dismissed from the combine, but Sokolaev and Vorobyov soon formed a photo laboratory at another enterprise and continued to work jointly. In the words of Sokolaev, ‘once deprived of the factory, we took our Leicas and went out on the streets of our native city’.

The TRIVA members had their own concept of photography, gradually and uncompromisingly developed, therefore we may refer to these photographers as a school. There was complete absence of the staged composition that dominated official Soviet photographic art. They also practised strict non-interference in the event under documentation, rejected artificially created ‘artist embellishment’ and printed full-frame images. Vladimir Sokolaev describes the principles and interests of the group as follows: ‘The theory of photography was very seriously examined, its origins as reportage (...). Use of the regular 50 mm lenses became a determining factor, since they produced photography that retained a perspective customary for the human eye, with the sense of a ‘window on events.’ The method of immersion in an event became the basic photographic technique. To emphasise the all-encompassing nature of the document we began printing the whole negative, including the perforations. After a while we omitted the perforations in our prints, it seemed too ‘arty’, but we still print the full negative, to this day...’

After dismissal from the combine, the photographers no longer had access to official exhibitions and their work was kept ‘for the desk drawer’. The majority of photographs that can be viewed today in MAMM were once only accessible to a narrow amicable coterie of photographers, by means of apartment exhibitions and samizdat photo albums. Theoretical interpretation and critical reactions to their photography were also limited to a close circle: when in Moscow the photographers met with Alexander Slyusarev, Valery Shchekoldin, Vladimir Semin and Yuri Rybchinsky.

Today, thirty years later, the TRIVA photographers have gained the recognition they deserve. In 2013 a large-scale exhibition entitled ‘TRIVA Manifesto of the Proletariat’ was compiled by the Siberian Centre for Contemporary Art and shown in Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, St. Petersburg, Novosibirsk and Kemerovo.

With the exhibition ‘Novokuznetsk School of Photography’ MAMM continues to bridge gaps in the history of Russian photography. Vladimir Sokolaev has for many years actively preserved, systematised and described the creative legacy of the TRIVA group, and the Museum is indebted to him for assistance in preparing this exhibition.

General information partner |