New York. 1955

William Klein. 4 women, supermarket, 1955. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

William Klein. Woman + cigarette holder, 1955. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

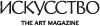

William Klein. Rheingold, 1954–1955. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

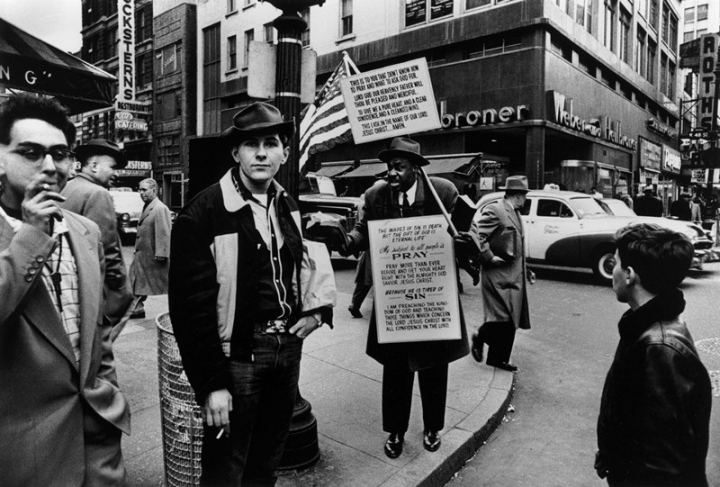

William Klein. Pray + Sin, 1954. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

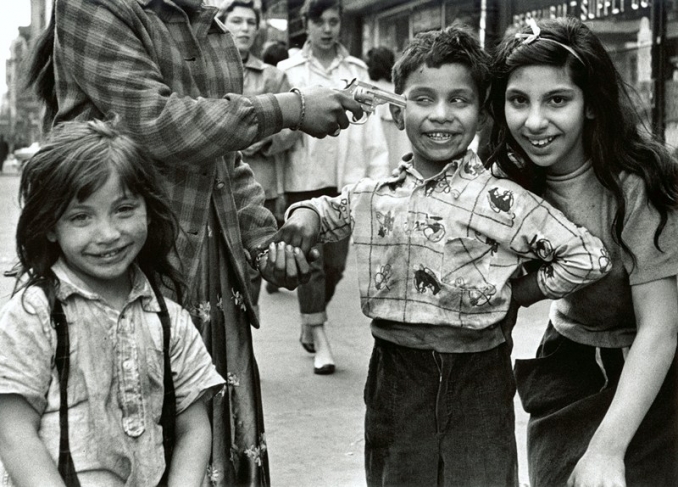

William Klein. Gun 2, 1954. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

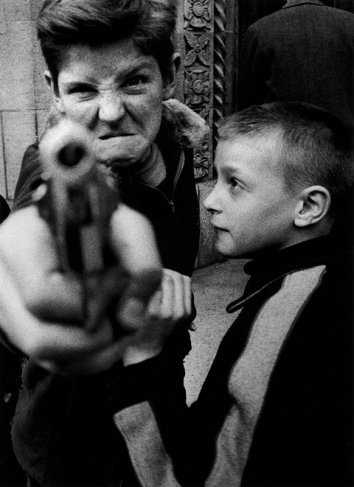

William Klein. Gun 1, 1955. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

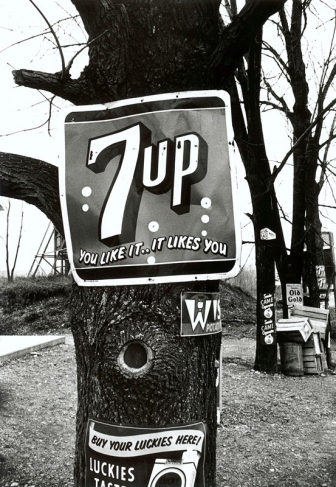

William Klein. 7UP, 1954–1955. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

William Klein. 75 + Fight Communism, 1955. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

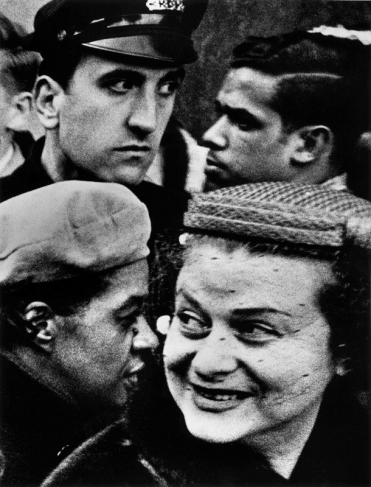

William Klein. 4 heads, 1954. Gelatin silver print. Artist’s collection

Moscow, 7.03.2012—15.04.2012

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

I finished my service in the US Army after the 2nd World War in Paris and decided to stay there and become a painter. I worked in the studio of Fernand Léger. He urged us 20 year old apprentice genius painters to forget about careers, galleries & collectors, to get out of the studio and work in the city, with architects, like the artists of the quatro-cento. In the beginning of the 50’s I had the chance of exhibiting in Milan and showed mural projects and then had the good luck of getting a commission from a young architect to paint a mural on turning panels that divided a large area. And this, curiously led me to photography. The panels were painted on both sides and slid on rails and swivelled. I photographed the result with long exposures and had someone turn the panels. My painting at that time was hard edged with geometrical patterns: triangles, circles, and thick stripes. Turning the panels made the forms blur and I discovered now they were transformed by the blur. For me, this was a way to get out of the rut of geometrics and thanks to photographic blur find new forms & solutions.

Returning to Paris, I pushed the abstract forms transformed by blur, so photography opened a new way of developing my abstract designs. I now had a dark room &, for the first time, I was able to blow up the photographs I had been taking, of my wife, on travelling, on vacation and I realized that these photos that didn’t look like much coming back, out of focus, with thumb marks, from the corner drug-store weren’t as had as all that. Photography brought me out of abstract geometrics and gave me the possibility to say something about the world around me which my geometrical painting did not. So photography opened up my painting and opened up my eyes on the world. I had no photographic training and my pictures were rough and funky. I didn’t care and used a what I had learned as a painter, drawing with charcoal and doing lithographs, to make my own kind of photographs.

I had the opportunity to return to New York and with my new discovery I decided with my 25 year old nerve to do a book, a photographic diary of my return to my home town. My photos were far from classic but they suited me. It didn’t matter. If I had a negative that I could put it in the enlarger I could always make something out of it. I had had a show of my abstract photos in Paris and had received a call from Alex Liberman, the art director of Conde Nast, asking me to come to see him. He said, «Would you like to work for Vogue?» Doing what? I asked. I don’t know, he said, be an assistant art director, take photos. I like your experiments, Do you have a project? I said yes, to do a book on my return to New York. OK we can finance you and publish a portfolio. How could I refuse?

Back in New York I plunged into my project, taking photos, day & night, any way I could. Liberman went along with the project and gave me a contract. I did portraits, still lifes and so on for the magazine and Vogue paid for my expenses on the NY diary project. I began to know a little more what I was doing with a camera and helter skelter, developed a way of photographing. I assembled the photos and showed them to New York editors. They were horrified, too grainy, contrasted and blurred . This is not New York, you make it look like a crazy slum. I said, New York is a crazy slum. What do you know? You live on 5th avenue and come to the office on Madison. Have you ever been to the Bronx? So no American edition. I returned to Paris and showed the pictures to a French editor, who flipped, we’ll publish the book. My violent Dada take on New York excited French imagination and the book was done. When it came out: strong reactions, for and against, but, in general, it was hailed as a departure from classic photography, a new and surprising take on photography. The book was strange and funky but it was out there and gained recognition. It won the Prix Nadar and opened horizons for me. In 1957 I met Fellini who already had a copy of the book and invited me to come to Rome to be his assistant on his new film, the Nights of Cabiria. Why not, I went to Rome but the film, as often in cinema, was delayed. So I stayed in Rome and said to myself, you’ve done a book on New York why not do one on Rome? Which I started to do. From there, many opportunities presented themselves, a Japanese editor invited me to do a book on Tokyo and was willing to publish the book on Moscow that I had started to make. Photography began to be my first preoccupation. Vogue never published the portfolio on New York that they had promised but asked me to try my hand on fashion photography. Fashion didn’t interest me but the opportunity of going from primitive photography to sophisticated with unlimited technical means intrigued me and I tried to see what I could do with this new opportunity. I found fashion photography outside of Penn and Avedon, stilted and banal and tried to shake up the scene.

Photography had become my main preoccupation and source of revenue. Eventually I did five other books on cities went on to film making with about 20 films documentaries and fictions and now, even with the recent series of painted contacts back to painting.

William Klein