Nikolai Bakharev

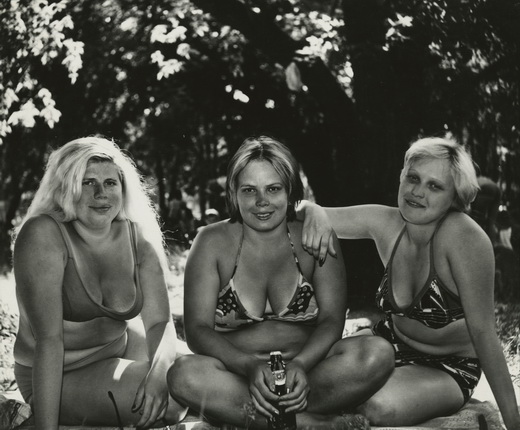

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 28. 1988-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Interior», № 7. end of 1980s. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

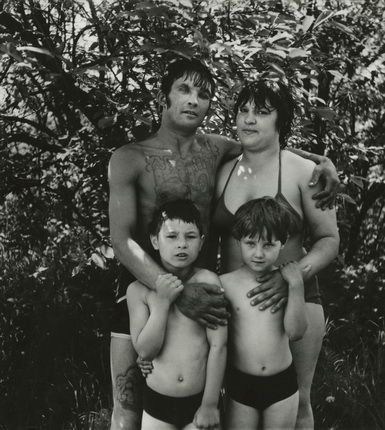

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 2. End of 1980s. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

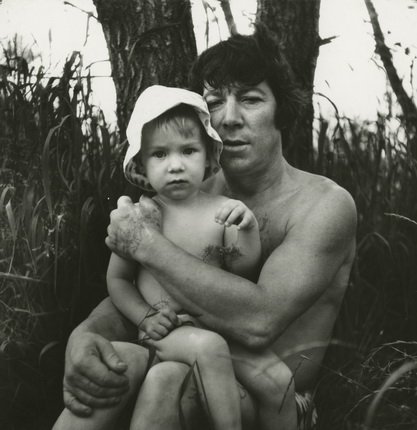

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 3. 1988-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

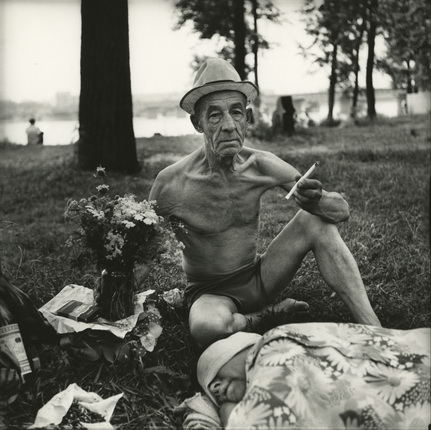

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 25. 1988-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 23. 1988-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 17. 1988-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», № 5. 1988-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

Nikolai Bakharev. From the series «Relationship», №51. 1991-1993. © MAMM, Moscow / Nikolai Bakharev

Frankfurt am Main, 20.06.2015—20.09.2015

exhibition is over

Museum fur Moderne Kunst

Domstraße 3 60311 Frankfurt am Main

www.mmk-frankfurt.de

Share with friends

Deutsche Börse Photography Prize 2015

Exhibition shedule

-

17.04.2015—7.06.2015

London

The Photographers' Gallery

-

20.06.2015—20.09.2015

Frankfurt am Main

Museum fur Moderne Kunst

For the press

Nikolai Bakharev is one of the most important and enigmatic figures in Russian photography of the late 20th century.

A provincial portrait photographer, from the early 1990s he became an acclaimed artist in Russia and abroad. Bakharev’s works were shown in group and solo exhibitions and became part of museum and private collections. In 2013 they were exhibited as part of the main programme of the 55th Venice Biennale and at the Rencontres d’Arles.

Nikolai Bakharev was born in the village of Mikhailovka in the Altai region in 1946. At the age of four he was orphaned and subsequently grew up in a children’s home. Bakharev began his working life at a metallurgical plant in Novokuznetsk, one of the largest industrial cities in western Siberia. At the age of 24 he became a professional photographer, working in a service centre. In the 1960s, as a result of Khrushchev’s urbanisation policy and the planned construction of large industrial complexes, the service centre became the focus of everyday life for the city-dweller, a place where they could have shoes, watches and refrigerators repaired, cut keys, have clothes made or altered and also order photographs to mark important family events such as weddings, births and graduations.

In the Soviet Union at that time the profession of photographer was considered to be on a par with that of manual labourer. This did not stop the service centres, even in Russian provincial cities, from giving birth to a whole generation of important photographers who, thanks to their work, made enough money to live on and gained technical experience, trying to use their spare time for their own work. In Perm the wonderful photographer Andrei Bezukladnikov started his career in a service centre. Despite the low social status of photographers, an encounter with one was a special experience for the ordinary person. It was that rare moment when they became the centre of attention and the possibility of self-identification appeared, something which did not exist at work or at home. For this reason money for a photographer was scraped together even by those earning very low wages.

Bakharev worked only to order. Unfortunately few photographs remain from that time, but even from those group portraits one can see how the photographer’s aesthetic system was formed and then barely changed. Commissioned photographs had to appeal to the client, so Bakharev carefully fixed the composition and poses and caught his subjects at moments of happiness and maximum self-expression, all the while observing the necessary distance. This aesthetic distancing from the object of the photograph, while fully engaged in the creation of the composition, was atypical for Soviet photography at that time. In the 1970s Soviet photography was developing in two directions. The first was according to the canons of socialist realism, i.e. staged reportage which, since the early 1930s, had become typical of photographers working for the Soviet press, who had to fit within the strict framework determined by the ideological system. Simultaneously there was a trend arising out of amateur photography, which appeared during the Khrushchev «thaw» of the late 1950s and early 1960s, when the genres of landscape (the space of naturalness and freedom) and the psychological portrait (which had practically disappeared after the revolution) resurfaced. This romantic line, where individuality and the internal world of a particular person are the primary focus, was a reaction to the totalitarian system’s canons of socialist realism, which unified people to the point of social generality — the Soviet people.

Bakharev doesn’t fit within either of those directions. One might say that he photographs his subjects using the aesthetic of naive art or art brut, levelling out to the maximum the artist’s presence, which remains backstage and appears only at the moment of staging, of setting the mechanisms of self-presentation of his characters.

In the late 1980s, during perestroika, the entire structure of Soviet life, including the service centres, began to perish, like a drowning Atlantis. Photographers had to find their own clients: kindergartens, schools, weddings, girls wishing to shoot a portfolio and beaches, where holidaymakers want to be photographed with their friends and relatives. The beach is a moment of happiness, a celebration, a time when people break out of their daily routine and try to find themselves in nature.

Nikolai Bakharev shot the «Relationship» series in the late 1980s and early 1990s on the beaches of Novokuznetsk. These apparently ordinary «beach» photographs, of a type made by many photographers in the Soviet period, became classics of Russian photography, a portrait of the epoch at a point of historical rupture (the Soviet Union ceased to exist in 1991).

People shed their clothes on holiday, and with them the social determinism of the Soviet person, who was educated and lived like a cog in the system, with any individual differences, including gender, maximally evened out.

These undressed people posing for a street photographer spontaneously expressed a craving for togetherness. It is probably no accident that most of the portraits feature groups of people. It’s curious that, more often than not, it is men sitting on women’s knees rather than the other way round. In fact it was Soviet men who were affected and deformed by socialism as a social epidemic. Not having the possibility to earn in accordance with their qualifications and abilities, men could not take responsibility for their wife and children and, more often than not, became infantilised or drank heavily. The Soviet woman, responsible for the survival of her family, fulfilled the role not only of the beloved but also of mother, adopting her husband.

Only in the early 1990s, with the birth of unfettered capitalism, did the situation change. We see an awakening machismo in the young men in Bakharev’s photographs. The «Relationship» series is a tough ethnographic portrait of the Russian provinces. The photographs exude the characteristics of degradation as a consequence of the transformation of the personality of the social system (this is the origin of the term Homo sovieticus, used in both foreign and Soviet media). At the same time Nikolai Bakharev’s photographs are full of warmth and open (sometimes naively) emotionality, which are inherent even in the most lost and unprotected people.

In a country where sexuality and the naked body had been censored since the mid-1930s, Bakharev’s works became an important part of unofficial culture as a whole and of unofficial photography in particular.

From the mid-1990s, having somewhat recovered from the shock of the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia tried to find directions for future development. At that moment there arose a demand for a personal history, even one which was recent.

Nikolai Bakharev’s «Relationship» series turned out to be not only a history, but the present day of a country which has been stuck between the past and the future for almost a quarter of a century.

Olga Sviblova