Photos by Mickey in collaboration with Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid

Moscow, 10.02.2016—8.03.2016

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

As part of the 11th International Month of Photography in Moscow ‘Photobiennale 2016’, MAMM and NCCA present the project ‘Photos by Mickey in Collaboration with Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid’.

‘My first work with Alik Melamid on co-authorship with animals was back in 1978. Then it was pictures with Tranda the dog. Prints her right paw made on paper created realistic images. Then, in the 90s, we taught elephants abstract painting, and later worked on projects for developing the architecture of beavers and termites: their dams and towers.

In my opinion the beauty of forms created by animals is not ‘beauty in art’, but ‘beauty in nature’. It is conceptually distinguished from ‘beauty in art’. This is the beauty of clouds and crystals, dawn and dusk. My perception of ‘beauty in nature’, as distinct from my perception of ‘beauty in art’, does not depend on the historical context, on my knowledge of the history of styles, biographies of the authors, etc.

I see the photographic works created by Mickey as dualistic natural phenomena. They lie at the boundary between natural science and art history. At the boundary between the mysterious, and the comical.

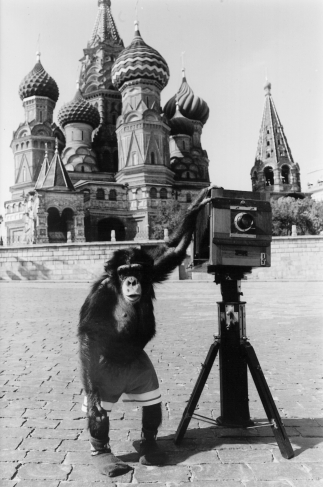

I first saw Mickey in 1996, when I visited Moscow Circus with my son. Mickey was not an ordinary chimpanzee. He was born in Moscow, to a family of intellectuals. His parents worked at the I.P. Pavlov Scientific Research Institute. At an early age Mickey showed an amazing sense of musical rhythm and talent as a dancer. A few years later he became the star of Moscow Circus. The public, especially children, adored him. During his performance I saw that for Mickey this was not work, but more like pleasure and the joy of creativity. Like many artists, he loved attention and the audience’s ecstatic applause. There came a moment when I understood Mickey as a parody of myself. As my new potential colleague and co-author. It has long been common knowledge that monkeys demonstrate ability and love for drawing, but none of us remembered them taking photographs. This gave me the idea that I could broaden the range of Mickey’s display of natural talent and acquaint him with the new opportunities offered by photography.

Co-authorship with Mickey was not an experiment like those carried out by Pavlov or an animal trainer in the circus. For me the work with Mickey was an experiment conducted on myself. In childhood I felt an inexplicable sense of guilt. This went away if I fed or cared for animals.

I had a tortoise, hedgehog, dog and mouse, plus two tanks with fish. One day I saw my puppy begin to play with a cluster of wild flowers. I watched this game for a long time, and suddenly understood that the puppy’s attitude to this plant was the same as mine towards the puppy. Now I became aware that my love for animals was a kind of dialectical hypocrisy. I was increasing my sense of self-worth by contact with ‘our lesser brothers’. Probably this unexpected flash of self-critical consciousness was the starting point of my new attitude to animals.

Later, after Mickey’s death (in 2007), it occurred to me how deeply our co-authorship had influenced me. I wasn’t the teacher, it was Mickey. He taught me an important lesson. I see Mickey as a grotesque play on my own self. He was my crooked mirror from the ‘hall of fun’. It is no coincidence that in many languages, including Russian, the expression ‘to monkey around’ is a synonym of the verb ‘to imitate’.

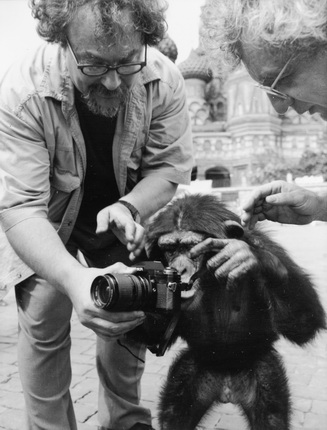

The work process with Mickey was not at all like the co-authorship Alik and I practised with elephants. To begin with Mickey familiarised himself with different cameras: from the antique to the very latest model, these mechanical toys played the role of a barrier between us. Only after I gave him a Polaroid did he see the gradual development of an image. Mickey understood and learned the connection between the appearance of a photograph and the movement of his finger as he pressed the button on the camera shutter. After perceiving the link between what he saw in reality and what he saw in the photograph, our work with ordinary cameras speeded up considerably.

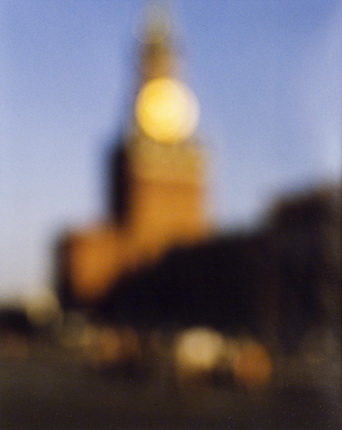

As co-author I helped him adjust the definition. But Mickey would press first his forehead, then his nose on the lens and disrupt the focus. As a result his photographs of the famous St. Basil’s remind me of Claude Monet’s misty Impressionist cathedrals.

In the composition of the photographic works by Mickey I see something beyond the range of human perception. These visions of a ‘new and other world’ lead us to the same place as Rodchenko’s perspectives. The discovery of an unknown view of the world is always a valuable phenomenon — seeking and finding an ephemeral photo-moment, a hopeless attempt to escape from the generally accepted historical context. Inevitably accompanied by photographic documentation of the shooting process (P. Degtyarev), these works by Mickey are both mysterious and comical.’

Vitaly Komar

General information partner |