Memory and light. Japanese photography, 1950-2000

From the collection of the European House of Photography, Paris, France. Dai Nippon Printing Co., LTD donation.

Shoji Ueda. Ken Domon sur les dunes, 1949. Collection Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris. Don de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. © Shoji Ueda Office

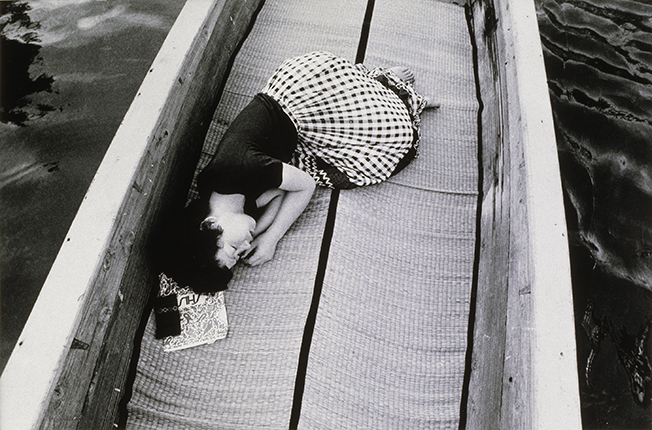

Nobuyoshi Araki. From the ‘Sentimental Journey’ series. 1971. Author’s silver gelatin print. Collection de la Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris. Donation de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japon

Ryuji Miyamoto. Architectural Apocalypse Expo 85 Pavilion. Tsukuba, 1985. Silver gelatin print. Collection de la Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris. Donation de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japon

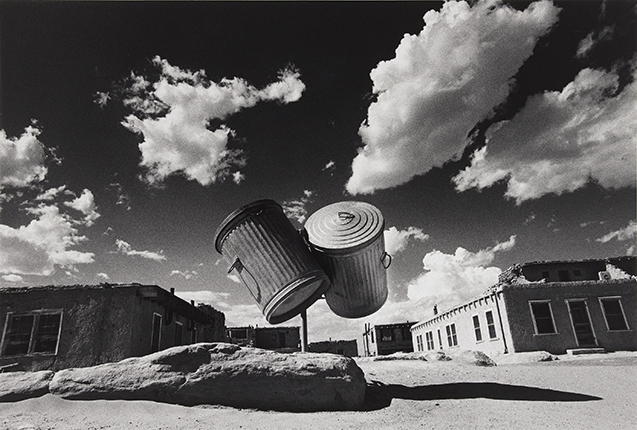

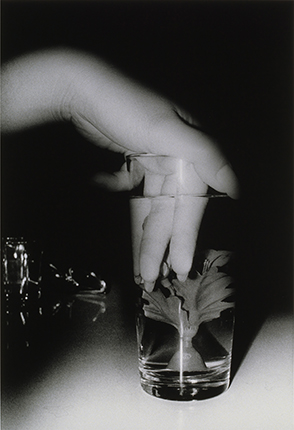

Ikko Narahara. Where Time Has Stopped #7. New Mexico, USA. 1972. Author’s silver gelatin print. Collection de la Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris. Donation de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japon

Daido Moriyama. Untitled. 1988. Silver gelatin print. Collection de la Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris. Donation de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japon

Naoya Hatakeyama. River Series #4. 1993. Chromogenic colour print. Collection de la Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris. Donation de la société Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japon

Moscow, 6.04.2018—3.06.2018

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curator: Pascal Hoёl

For the press

XII INTERNATIONAL MONTH OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN MOSCOW PHOTOBIENNALE 2018

Year of Japan in Moscow

Memory and Light. Japanese Photography 1950—2000.

Gift of Dai Nippon Printing Co., Ltd. From the collection of the European House of Photography (Paris)

Curator: Pascal Hoël

Working group: Frédérique Dolivet, Diane Kitzis

As part of the Photobiennale 2018 and the Year of Japan in Russia, the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow presents the exhibition ‘Memory and Light. Japanese Photography, 1950—2000. Gift of Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd.’ from the collection of the European House of Photography (Paris).

In 1992 the major Japanese printing company Dai Nippon Printing Co. Ltd., at the initiative of its President Yoshitoshi Kitajima, resolved to acquaint the French public with contemporary Japanese photography and presented the European House of Photography (Maison Européenne de la Photographie, or MEP) with an extensive collection of works by eminent Japanese photographers of the 1950s to 1990s.

From 1994 to 2005 the MEP collection was annually enriched with outstanding photographic series by Japanese masters, and today consists of 540 works. This is the largest collection of Japanese photography in Europe and clearly demonstrates the important role of Japanese art in the history of world photography.

The МАММ exhibition showcases the part of the collection covering a period from the late 1950s to early 2000s, including works by classics of postwar Japanese photography and leading photographers who are now world-famous, such as Nobuyoshi Araki, Masahisa Fukase, Seiichi Furuya, Naoya Hatakeyama, Hiro, Eikoh Hosoe, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Miyako Ishiuchi, Ihei Kimura, Taiji Matsue, Ryuji Miyamoto, Daido Moriyama, Ikko Narahara, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Keiichi Tahara, Hiromi Tsuchida, Shomei Tomatsu, Shoji Ueda and Hiroshi Yamazaki.

Over decades marked by the tragic events of the 6 and 9 August 1945, when Japan experienced atomic bomb attacks, and the American occupation that lasted until 1951, followed by economic upsurge in the 1960s, generations have come and gone in the country and witnessed both social upheaval and turbulent economic growth. In the 1960s opposition movements liberated art and in particular photography, notably thanks to the legendary photography magazine Provoke, published between 1968 and 1969, from the strict limitations of previous years. Artists learned from each other, constantly exploring new techniques and genres that would not be confined to traditional visual canons.

Some photographers turned to the genre of photo reportage, revealing the consequences of one of the most horrific tragedies the 20th century had seen, while others told personal stories, resurrecting lost love or family secrets. Many photographers born after the war chose the theme of identity, examining Japanese traditions and myths. Authors such as Yasuhiro Ishimoto, Hiro, Keiichi Tahara and Seiichi Furuya lived and worked outside Japan for many years, and their work is so universal that it cannot be defined as merely ‘Japanese photography’.

Ihei Kimura made an important contribution to photography becoming an independent art in Japan and abandoned the aesthetic experiments of that time, using photography as an instrument for ‘objectively’ recording reality. Working in the central Japanese mass media, he created a unique chronicle that reflected the country’s rapid development after the Second World War.

In Shoji Ueda’s photographs his native province of Tottori is hidden from the hectic life of Tokyo by surreal dunes. For 30 years, from 1949 to 1980, he worked on producing a photo series that conveys his neighbours and relatives with genuine humour and poetic simplicity, placing his subjects in a natural theatre formed by sea and sands.

Yasuhiro Ishimoto was educated at the Chicago Institute of Design, where he studied with Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind in the early 1950s. He participated in the exhibition ‘Always the Young Strangers’, organised by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1953, and in the comprehensive ‘New Japanese Photography’ exhibition in 1974. Ishimoto brought innovative ideas to Japanese art and surmounted the concept of nationality in photography in a manner more striking than that of any other photographer.

Shomei Tomatsu, Eikoh Hosoe and Ikko Narahara were co-founders of the Vivo agency, which existed for just two years yet marked a turning point in the history of Japanese photography.

Shomei Tomatsu, one of the classic postwar Japanese photographers, is the author of works on Nagasaki in the era of chaos that swept Japan from the 1960s to 1970s.

Eikoh Hosoe achieved recognition by means of two unforgettable and exquisitely published albums, ‘Barakei’ (1963), dedicated to the famous writer Yukio Mishima, and ‘Kamaitachi’ (1969), where he recreates legends heard as a child, assisted by Butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata. Due to the success of these two works in which myths and traditions are entwined with reality and mise en scène, Hosoe rates among the foremost photographers of his generation and has gained well-deserved recognition in France and the USA.

Ikko Narahara is the author of photographic essays on which he worked for a period of 30 years. From the very first series about Hashima, an abandoned coalmining island (‘Artificial Territory: The Island without Flowers, 1954—1964’) to his travels across Europe (‘Where Time Has Vanished, 1970—1972’), he shares his ideas about time and space, obtained in the endless journey between light and darkness.

Daido Moriyama, now one of the better-known Japanese photographers, travelled to Tokyo in 1961 to join the Vivo agency, which had just closed. However, he managed to meet Shomei Tomatsu and became Eikoh Hosoe’s assistant. Moriyama quickly freed himself from the influence of his peers and overthrew all the dogmas of photography, making a definitive break with realism. His grainy contrasted images became a symbol of the new aesthetics of Are-Bure-Bokeh (‘obscure, coarse, out-of-focus’), which young Japanese photographers turned to in the late 1960s. Moriyama’s first book, ‘Nippon Gekijo Shashincho’ (‘Japan: A Photo Theatre’), published in 1968, was like nothing seen before and evoked an outcry. Nonetheless his vision was consonant with the aesthetics of Provoke magazine, with which he joined forces a year later. In 1972 Moriyama published the manifesto ‘Farewell Photography’, in which he expressed his final decision to abandon all forms of academic photography.

Hiromi Tsuchida’s Hiroshima series produced between 1960 and 1993 have much in common with the works of Shomei Tomatsu. Walking through the city 14 years after the tragedy, Tsuchida photographed people who had survived the bombing and the terrible exhibits preserved at the Hiroshima Museum; methodically and ruthlessly he examines remnants of the disaster and tries to analyse the consequences.

The work of Nobuyoshi Araki, a luminary of world photography, experimenter and provocateur, is represented at the exhibition by two of his projects. In 1971 Araki published his first book, ‘Senchimentaru na Tabi’ (‘Sentimental Journey’, 1971), a diary of his honeymoon. In the preface he writes: ‘‘Sentimental Journey’ is the fruit of my love and my determination as a photographer. I do not pretend to claim that these images are truthful, since I was shooting my own honeymoon. I chose love for my photographic debut, and the fact that it turned out to be a personal romance is purely coincidental. As for me, I think I will go on working in this direction because that’s how I can best approach the spirit of photography’.

In 1990 ‘Sentimental Journey’ was continued by the series ‘Winter Journey’, in which Araki accompanies his wife on her final path, capturing their last few moments of happiness, her funeral and his own loneliness. Gradually his cat Chiro occupies a central place in the photographs, as if she had become an emanation of the deceased.

Masahisa Fukase’s series ‘The Solitude of Ravens’ and the book he published in 1986, created after a painful parting from his wife, act as an expression of his despair and loneliness.

For his work on the series ‘Heliography’ (1974), named in honour of Nicéphore Niépce, Hiroshi Yamazaki left his camera on the seashore and followed the sun’s course, thereby overcoming the static nature of photography. His images resonate with the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto in the ‘Theatres’ series, begun in 1978. Sugimoto placed a camera at the centre of the first balcony of sumptuous theatres built in the USA in the 1920s and converted into cinemas, leaving the lens wide open throughout the showing. As a result he encapsulated the entire film in one frame.

The generation of photographers born after the war (Ryuji Miyamoto, Naoya Hatakeyama and Taiji Matsue) explore the aggressive impact of humanity on the environment, showing how man tries to ‘tame’ a landscape, sometimes until it entirely disappears.

Seiichi Furuya has created a touching series of portraits of his wife Christine Gössler, from their wedding in Graz, Austria, in 1978 until 1985, when she committed suicide while suffering from schizophrenia.

Miyako Ishiuchi tells the story of his mother, who died at the age of 84 in the late 1990s, taking photographs of her belongings as precious relics.

The photography of Hiro, who has built a successful career in the USA, is represented in this exhibition by the bizarre and colourful series ‘Fighting Fish’ (1984). Inspired by the ideas of Alexey Brodovitch, legendary art director of Harper’s Bazaar, Hiro has collaborated with the magazine for several decades, gaining recognition by his unique, instantly recognisable style and love of creative experiments.

Keiichi Tahara, who began his career as a photographer and worked for many years in Paris, is showcased by a series of expressive black and white portraits of eminent artists and writers from the early 1980s.