Land of My Father

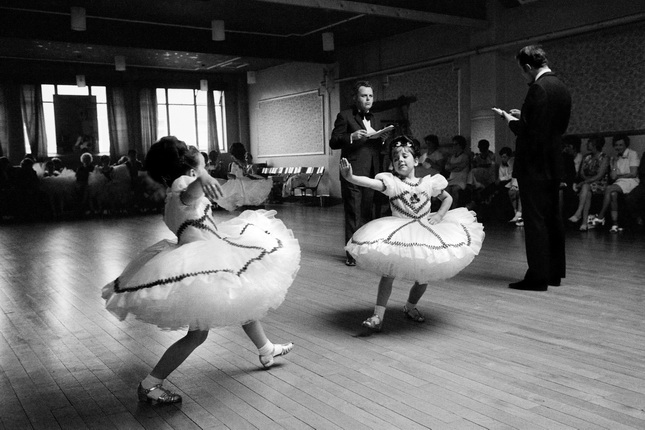

David Hurn. Bargoed. Junior Wales ballroom dancing championships. From the series ‘Land of My Father’. 1973. © Magnum Photos

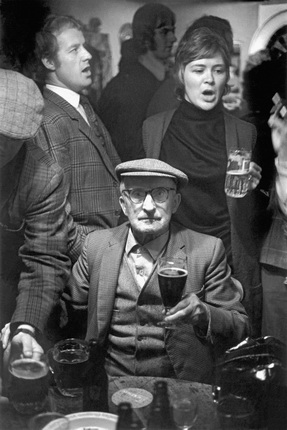

David Hurn. Sennybridge. Pub sing a-long. From the series ‘Land of My Father’. 1973. © Magnum Photos

David Hurn. Llanidloes. The local brass band lead the last Civic Parade to be held in Llanidloes. From the series ‘Land of My Father’. 1973. © Magnum Photos

David Hurn. Neath Valley, Black Mountain Coal. From the series ‘Land of My Father’. 1993. © Magnum Photos

Moscow, 13.03.2014—20.04.2014

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Project presented by Magnum Photos

For the press

David Hurn is a key figure in British photojournalism. He began his career in 1955 as an assistant at the Reflex Agency, but at the age of 22 he had already gained global recognition as the author of reportage on the Hungarian revolution (1956). Eleven years later, in 1967, he became a member of the legendary Magnum Photos cooperative, and in 1973 founded the acclaimed School of Documentary Photography in Newport (Wales). He has travelled the world giving master classes.

Hurn was born in England in 1934, but his father was Welsh. This factor proved highly significant for his work as a whole: for many years Wales, one of the four large administrative and political constituents of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, stayed at the focus of David Hurn’s photography. Hurn speaks of the inherent division between English and Welsh culture as follows: ‘My father and his forebears were all born and lived in Wales. By a quirk of timing I was born in England. Although quickly reinstated to our South Wales family home, the spectre of ‘born in England’ has permanently hung over me. The exploration of this dichotomy has been a driving stimulation in trying to understand my culture. I have wanted to discover my place in Wales and explore my contact with my fellow Welsh. If one examines life, then one should follow the argument wherever it leads. My tool is photography and the nature of photography is that, as you work, you continually record a world that has gone forever yet continually see the new unfold in front of you.’

Hurn’s photographs documented the Welsh world ‘that has gone forever’ over a period of more than twenty years. For Wales, the end of the 20th century marked a period of profound and dramatic change. Until then the economy, culture and landscape of the country had been dominated by agriculture and the heavy industries of coal, steel, and slate, but now the mines, mills and quarries have closed. A few remain, but only as tourist attractions. In 1974 Hurn recorded images of the still-operational Shotton Steel Works, but by 1997 all that was left to photograph was the National Coal Museum. Industrial production has been replaced by new high-tech industries and tourism, introducing fast food, film, television and the internet to the everyday life of the Welsh people. Hurn’s wide-ranging photo chronicle is valuable precisely because it captures these metamorphoses.

In 1966 Hurn visited the village of Aberfan, scene of the gravest tragedy that ever befell the old, industrial Wales: after torrential rain, a landslide covered the village with thousands of kilometres of slurry, burying twenty houses and a primary school. 116 children and 28 adults perished, and in Hurn’s photographs we see two of the surviving schoolchildren as they watch the rescue attempt.

Other images Hurn took in the 1960s and 70s show the traditional gathering of Welsh bards at Carmarthen, a family relaxing during so-called ‘miners’ week’ when all the miners took their holidays (this tradition disappeared after the mines closed), farmers at the Llanybyther Horse Sales, and young people playing push ball (their aim is to push a huge inflated ball over the opposition’s goal line). In 1993 Hurn took photographs at a Black Mountain coal mine, where they still used pit ponies to bring rock debris to the surface: by now the ponies no longer lived permanently underground as they did in the 19th century, only spending as long as was necessary in the mine to retrieve the coal. Each had an individual handler who was responsible for their health and cleanliness. In Hurn’s photograph a pit pony peers into the miners’ rest room.

In Hurn’s photographs taken in the same years, Japanese factories producing microchips and digital technology, hamburger stands, Asian tourists visiting the Welsh coast, discos and even male strippers appear side-by-side with scenes from the life of the old, traditional Wales.

Every picture tells its own truth about life in Wales now and in the recent past, providing a distillation in exquisite miniature of the all-encompassing change the country has undergone.