Photo Correspondent

Yuri Krivonosov. Jūrmala. 1965

Yuri Krivonosov. Azov Sea. 1970

Yuri Krivonosov. Volga. 1957

Yuri Krivonosov. Dance floor. Geologists’ camp. 1958

Yuri Krivonosov. Pamir. 1960

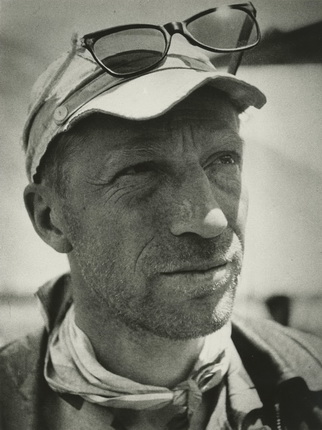

Yuri Krivonosov

Yuri Krivonosov. Norwegian Sea. 1964

Yuri Krivonosov. Foggy evening. Moscow, 1955

Yuri Krivonosov. Ruslan and ‘Ludmila’. Moscow, 1968

Yuri Krivonosov. Pensionable age. Moscow, 1960s

Moscow, 1.07.2015—6.09.2015

exhibition is over

Share with friends

This exhibition presents photographs by Yuri Krivonosov from the 1950s-1970s, when he was press photographer at the legendary Ogonyok magazine, the Soviet Union’s leading illustrated periodical.

For the press

Yuri Krivonosov was born in Moscow in 1926. At the age of ten he followed diagrams in a children’s magazine and constructed a cardboard box that could take photographs, using cine film supplied by a neighbour, Soyuzmultfilm cameraman Nikolai Voinov. Voinov advised the young photographer on how to develop and process his shots. Three years later Yuri’s father gave him a professional camera, the Fotokor, which Krivonosov has kept to this day and which remains in excellent working order.

After the war and graduation from the Naval and Aeronautical College as aerial photoreconnaissance specialist, in 1951 Krivonosov managed to secure a month’s work at Ogonyok magazine, deputising for an ailing technician in the photo laboratory. Who could have predicted that this month would turn into twenty-seven years.

His first photograph printed in Ogonyok (1953) was a panoramic photomontage compiled from fourteen separate shots of Stalin’s funeral. Krivonosov had been on duty continuously for three days and nights at the Ogonyok photo lab, and in the few hours’ break before the new issue went to press he ventured out for a walk through town, taking his friend’s FED camera. But he found the centre closed off. Skirting the cordons, by chance Krivonosov found himself in a side street that led directly to the Kremlin. The funeral ceremony had just begun on Red Square. Krivonosov climbed up on the ground-floor windowsill of a nearby house (some local lads helped him keep balance) and using his extensive experience in aerial photography, took panoramic shots. ‘... Seven frames along the Kremlin, up above, and seven frames below, across the crowd of people, with overlap,’ recalls the photographer. As it turned out later, none of the film cameramen or press photographers had been present at that moment and in that spot. Only Krivonosov got to take the photograph! After the photo shoot he rushed back to the editorial office to develop and dry his film. He hastily printed 14 frames and made a composite of the ‘square’. The chief of the photo department saw the panorama and the image was printed on a double spread. That’s how Krivonosov became an Ogonyok press photographer.

With a good school of photojournalism behind him, the press reporter could work with a degree of independence, choosing a favourite theme that fascinated him ‒ extreme shoots. Krivonosov went rafting on the rapids of a Siberian river; for two days he was roped to mountain climbers scaling a perpendicular rock face in Pamir; he made several descents in a hydrostat to the bottom of the Barents Sea; drifted on the North Pole station in the Arctic Ocean; photographed fishermen in the Norwegian Sea in stormy weather (wind force 7-9); sent a photo report from the steamship location of the film ‘Striped Trip’, spending two weeks ‘in company with’ tigers; photographed an airlift of cattle across mountain ranges from Uzbekistan to Kirgizia; and lay in wait for wild pigs and deer in a forest in winter... Sometimes colleagues would ask him: ‘Why do you do it?’ His reply never varied: ‘It’s interesting...’

In addition Krivonosov was interested in photographing faces. His portraits were of people symbolic of their time — writers, actors, the ‘great and god’ from various countries and cosmonauts including Yuri Gagarin (before the latter acquired his scar), as well as portraits of the ordinary people without whom this epoch would have been impossible. He also wrote news reports, essays and short stories. He travelled the length and breadth of the Soviet Union and visited dozens of foreign countries.