Between sky and earth

Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Start of ZYX 24. Piru,Zissu,George, Lui. Dede and Rober trying to get off the ground. Rouzat September, 1910. © Ministry of culture and communications of France / Association of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s friends

Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Scaled-down model of Zissu biplane. Paris March, 1909. © Ministry of culture and communications of France/ Association of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s friends

Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Aviator Jean Chei in “Kodron” airplane. Issy-les-Moulineaux. February, 1910. © Ministry of culture and communications of France/ Association of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s friends

Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Landing of Rober to “Pik #3”. Rober, James and the farmer. Rouzat. September, 1910. © Ministry of culture and communications of France/ Association of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s friends

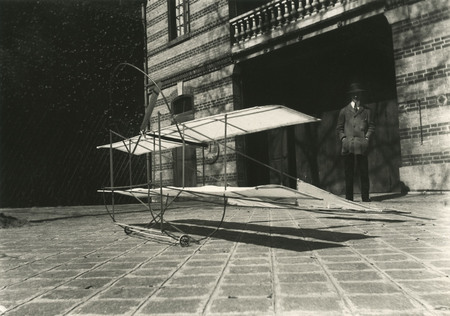

Jacques-Henri Lartigue. Zissu and his new airframe. Rouzat. July, 1914. © Ministry of culture and communications of France/ Association of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s friends

Moscow, 31.03.2009—26.04.2009

exhibition is over

Central exhibition hall Manege

1, Manege Square (

www.moscowmanege.ru

Share with friends

Presented by Association des Amis de Jacques Henri Lartigue, Minstry of Culture, France

Supported by the French Cultural Centre of Moscow and MasterCard Selection

For the press

Sorrow flies away on the wings of time

Jean de la Fontaine

...Once again I set off on my bicycle, riding in little zigzags lest I overtake Maman. As if I were gently flying all around her. Then I wake up. (Paris, 1903)

Jacques Lartigue was nine when he related this dream to his aunt Amelie, who jotted it down in her little black notebook entitled ‘Book of My Dreams’.

Early 20th century. The story begins with a happy childhood, two brothers born to a prosperous, harmonious and rather conformist family where everyone took delight in the world around them. Their father Andre, an entrepreneur with an unusually lively imagination and curiosity for his time, was an accomplished amateur photographer and initiated his son Jacques in the mysteries of the viewfinder and developing process. His instruction was restricted to the way the camera functioned: he was careful not to burden his apprentice with pointless constraints, to preserve the child’s freedom and spontaneity. Photography was a natural continuation of the ‘eye trap’ — this was what Jacques called a game he invented himself that involved opening and closing his eyes in an attempt to retain the pictures he saw.

I play at being a spectator, then suddenly an idea begins to dance in my head, a magical invention that means I shall never again be bored or unhappy. (Pont de l’Arche, 1909)

In 1901 his dream comes true and Jacques is given his very first camera (a Carpentier with 13×18 plates).

I can photograph everything. Everything! Everything! I used to tell Papa: ‘Photograph that, and this, and this...’ He would say: ‘Yes, of course’, but never did. Now I can do it myself. (Pont de l’Arche, 1909)

Jacques’ enthusiasm knew no bounds when his father bought him more sophisticated cameras that were lighter and easier to manoeuvre: the Bloc-Notes Gaumont with 4.5×6 plates and 1/300 exposure (1906) and the stereoscopic Spido Gaumont with 6×13 plates (1912).

* * *

Lartigue was truly a child of his time, an age when the phonograph, telephone, cordless telegraph and cinematograph had only recently been discovered. So many different ways to communicate! Often the entire family would discuss these new inventions and long for the appearance of the first automobile (in 1906 the Lartigues acquired a car with their own chauffeur). But a different adventure captured Jacques’s imagination, the conquest of the skies by airplanes — especially since he and his brother Zissou personally witnessed Gabriel Voisin’s flight at Merlimont on April 3rd, 1904. Voisin had covered 25 metres! This was the first time a machine heavier than air and with a man on board had flown in full view of the French public.

* * *

From 1907 to 1912 the two boys regularly visited the military training ground at Issy les Moulineaux. The new airplanes were tested here, adjusted and improved day after day. Zissou and Jacques also frequented Buc, Etampes, Villacoublay and even Monaco in pursuit of their heroes, aviators like Wilbur Wright, Alberto Santos Dumont, Roland Garros and Louis Bleriot. They made notes of new records (in speed, distance, altitude...). Moreover they subscribed to ‘La Vie au Grand Air’ et ‘l’Excelsior’, which described adventures in which they themselves participated, at one remove, as well as the popular air events they dreamed of attending.

Taking off! Soaring overhead! Passing over obstacles! Hovering immobile in

Although Jacques joined his brother’s games, all his talents as an inventor were concentrated on visual activities. Instinctively he understood what to do. With a trusty eye for detail he knew how to choose subjects and frames or the angle of the viewfinder. He manipulated cameras with the greatest of ease. Flat on his belly in his room, he would photograph miniature racing cars in the same way he observed the engines his brother made in imitation of larger models, animating them with his infectious enthusiasm.

For Jacques it was not only aircraft that took flight. Everything that moved fascinated him. At eleven he photographed his cousin Bichonnade in

Even before 1900 cameras could record a moving subject. But instant photography was an audacious rarity. In those days, too, using a camera was a slow process that demanded intense observation and concentration from the photographer, as well as a faculty for predicting the image. Jacques Lartigue was a master at this almost physical art.

He lived out his dreams through people or objects, and perhaps this made his images so dynamic. His brother Zissou roused him to action and grappled with reality (later becoming an engineer), while Jacques observed and recorded (he remained a photographer).

From 1912 Jacques Lartigue used a Nettel camera with 6×13 stereo plates. He avidly explored the opportunities for stereoscopic shots (Merlimont, views of games at Rouzat, airships, his brother’s airplanes and a few aircraft). Appropriating space through relief, he investigated a new line of enquiry: with the two-lens Nettel camera it was technically possible to dispose of one lens, if required. The images obtained were extended like a panorama, a format rarely used.

The year 1922 marked the first glider rally at Combegrasse. For Lartigue this invention was a new beginning. Test flights using these ‘engineless planes’ provided the photographer with new opportunities. Gliders had unlimited space to fly, glide, or even fall. This was no longer an impression of speed, but the miraculous ability to float in

* * *

Since childhood I have suffered from a kind of malady: all the things that delight me are forgotten, my memory is unable to retain them.

All his life Jacques Lartigue invested insatiable energy in his struggle with this demon, using every possible means to preserve his beloved moments in time. Naturally photography offered some consolation, but also the diary he kept from 1911 onwards. To begin with he depicted the weather (sun, rain, clouds), then quickly described his activities that day. He used the rest of the page to sketch what he had just photographed, in case he never saw it again (developing and printing were unreliable in those days). These rapid sketches are testimony to a perfect memory and eye: in a few strokes he portrays the oblique silhouette of an airplane above the crowd or a member of the crew gesticulating, pointing as a biplane rises from the ground. The drawings are mainly of airplanes

Later Lartigue used his notebooks to compile a more detailed diary from these hasty notes, this skeleton of memory.

More than simply recounting the facts that were important to him, he collected his photographs in large albums supplemented with handwritten notes. He told his own life story to himself.

For instance, a sketch in the 1911 diary depicts a plane soaring high in the sky, with marching soldiers in the foreground. The corresponding photograph is included in the album for 1914 and entitled ‘1914. War...?’

Jacques regretted that he never managed to capture some photographs.

This morning an inventor by the name of Monsieur Reichelt, a tailor by profession, threw himself from the first-floor platform with a parachute he devised himself. He began falling immediately and was killed. What a pity I didn’t take any photographs. (Paris, 1912)

Another example:

Today really is a wonderful day for me: an aviator tumbled to the ground quite close by, and I was able to photograph him. One of Bleriot’s pupils fell too, but that was less successful, too far away and he wasn’t thrown from the fuselage. (Paris, 1911)

When Lartigue found a photograph he would have liked to take, he bought the reproduction and pasted it into his album, incorporating it in his memoirs with the fervour of a true collector.

* * *

Zissou is making kites with Papa. I watch as they rise towards the clouds, dazed from breathing the air that carries them aloft. At the same time I am amused by the thought of a tiny rubber dolly I attached to the big kite without anyone knowing. Head-spinning sorcery: I can well imagine the feeling if it was me up there instead of that little chap! (Rouzat, 1906)

A paradox: Lartigue’s baptism in the air was delayed until the age of twenty-two, although he took photographs of early flights at ten. Apparently the spectacle was more than enough. No matter if the airplanes or ‘aviettes’ (remarkable winged bicycles) never took off. His excitement was unconditional.

Yesterday an airplane passed over me! Right over my head! From down below I saw a live human being perched in his seat, legs thrust apart... And suddenly there was a strange sensation in my head... A bit like vertigo in reverse! As if I had seen the man pass with eyes that were not mine, with his eyes!?!? I watched him fly into the distance, still borne aloft. His air-filled engine resonated through the air. Sometimes you have unique first emotions, but if you pursue them later they can never be retrieved. (Paris, 1909)

Martine d’Astier