In the gardens of my imagination

Paintings, graphics, manuscripts

Moscow, 20.12.2017—4.02.2018

exhibition is over

Share with friends

Curator: Anna Zaitseva

For the press

Fyodor Vasilyevich Semyonov-Amursky was born in Blagoveshchensk, studied at the Blagoveshchensk Arts and Industry Institute, and then moved to Moscow, enrolling at the Higher Art and Technical Studios (Vkhutemas), where, at that time, the traditions of the pre- and post-revolutionary avant-garde were still being preserved. In his youth he was fascinated and charmed by French painting, which he came to know on visits to the Museum of New Western Art. Having studied the works of the artists of the Paris school in detail, as well as those of the Russian artists of the beginning of the 20th century, Semyonov-Amursky included their language and ideas in his own artistic conception. He himself said ‘I am an artist standing on the shoulders of my predecessors,’ and liked to repeat that ‘an artist should combine the wisdom of Cezanne, the emotionality of Van Gogh and the naivety of Henry Rousseau.’

At the beginning of the 1930s, ‘the Great Turn’ took place in Russia, and the ‘socialist realist’ mode spread to all spheres of culture. A host of artistic groups were united into the Union of Soviet Artists, of which Semyonov-Amursky became a member, inconspicuously and passively remaining there right up until his death, earning his keep by retouching photographs for the Bolshoi Soviet Encyclopedia. Semyonov-Amursky’s art wasn’t in demand in the Soviet artistic system: his first modest exhibition only took place in 1967, at the Institute for Physical Problems of the USSR Academy of Sciences, thanks to the efforts of Pyotr Kapitsa; his second and final exhibition during his lifetime came in 1976, at the Central House of Arts Workers.

Not wishing to enter into any compromises with the Soviet authorities, neither in terms of aesthetics nor in terms of content, Semyonov-Amursky opted for escapism and a life within his own world, where his beloved French artists ruled supreme: Cezanne, Van Gogh, Denis, Dufy and Bonnard… The notebooks presented at the exhibition became, for the artist, a unique creative laboratory — within them, he discussed the techniques of painting, copied out extracts from the works of philosophers, artists and writers, and considered the nature of art. ‘I like to walk in the gardens of my imagination,’ Semyonov-Amursky said of his artistic process, which entirely filled and penetrated his life. ‘…This time, work, without wearing yourself out; but these continual discussions of art, your showings and the viewing of the works of other artists could melt away your last grains of fat and turn you into the remains of Saint Feodor’, his wife, Yelizaveta Izmailona Yeliseyeva, wrote to him in 1970.

Rejected by the official Soviet system, Semyonov-Amursky sought support in the old, romantic opposition of the artist and the crowd or public taste — many of his own notes and extracts copied from the biographies and texts of other artists are devoted to this theme. ‘The more lofty the artist, the less viewers he has,’ he said. Despite not becoming a dissident, and perpetually standing aside from anything that might in any way relate to politics, in 1967 he copied out the following remark from the book of comments at the ‘50 Years of Soviet Power’ exhibition: ‘Do we really not have any real artists who can get by without stereotypes, without demagoguery and without censorship, who live through human feelings, rather than through the commandments of the communist religion?’

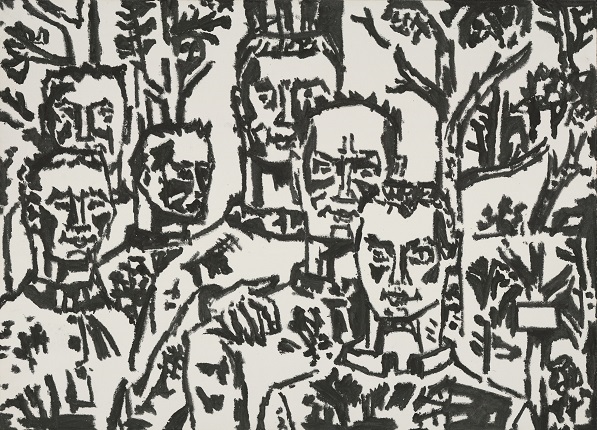

Semyonov-Amursky wasn’t an admirer of abstract art. ‘I love reality,’ he said. With few exceptions, his works are figurative: horsemen, flowers, faces, sculptures, still lifes, landscapes, group compositions. Nevertheless, the reality of Fyodor Semyonov-Amursky, who titled himself an ‘artist-idealizer’, transformed magically, becoming elevated and romantic.

Living conditions and financial constraints dictated Semyonov-Amursky’s working techniques and methods. The bulk of his life was spent in a tiny room in a communal apartment, and he painted on paper — it was cheaper, didn’t require a frame and took up a minimum of space. The room’s dimensions also determined the small format of the works — no more than half a sheet of sketching paper. In total, over the course of his life, Semyonov-Amursky created thousands of works, repainting them several times over, and often destroying them in ‘critical selections.’

The viewers of his works, for the most part, were friends and acquaintances attending rare home showings with tea and philosophical discussions. The current exhibition has been made possible thanks to Igor Shelkovsky, an artist and the publisher of a magazine on unofficial Soviet art, ‘A-Ya’, which was issued in Paris in 1979–1986. Shelkovsky first met Semyonov-Amursky in 1954, at the Pushkin Museum, in front of a picture by Matisse which had only just been presented there — the Soviet ideology regarded Matisse as being too much of a formalist, and so his works were usually kept in storage. Their friendship lasted right through until Shelkovsky’s departure for Paris in 1976. They stood in line together to attend the exhibitions of Picasso (1956) and Fernand Leger (1963) at the Pushkin Museum, and they attended the legendary American exhibition at Sokolniki (1959). Thanks to this acquaintanceship, a single social group in the 1970s united artists who were polar opposites but equally ‘unofficial’, artists such as Semyonov-Amursky and his students — Pavel Ionov, Ivan Smirnov, Grigory Gromov, Alexander Maximov — and ‘youngsters’, such as Dmitry Prigov, Rostislav Lebedev and Boris Orlov. After Semyonov-Amursky’s death in 1980, it was Igor Shelkovsky who organized his first exhibitions abroad, in Paris (1988 and 1992), making the sculptural frames for the paintings in which they are now being shown and in which their graphic appearance is in keeping with the graphic arrangement of the manuscripts of Semyonov-Amursky himself.