Bolshoi Ballet

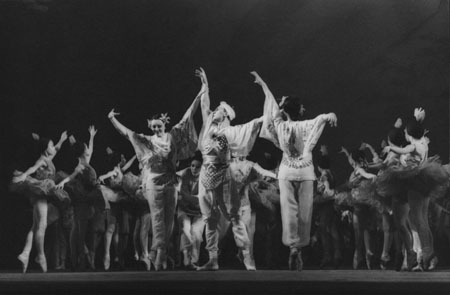

George Petrusov. Red Poppy. 1950. Dance of the birds

George Petrusov. Red Poppy. 1950. Tao-Khoa – Galina Ulanova

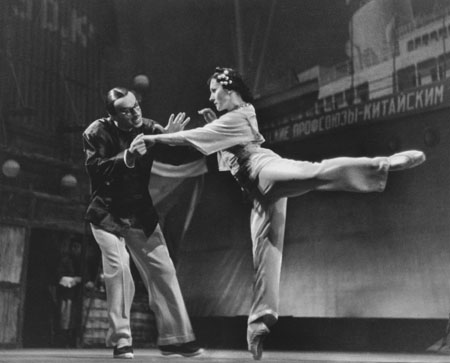

George Petrusov. Red Poppy. 1950. Scene from the ballet

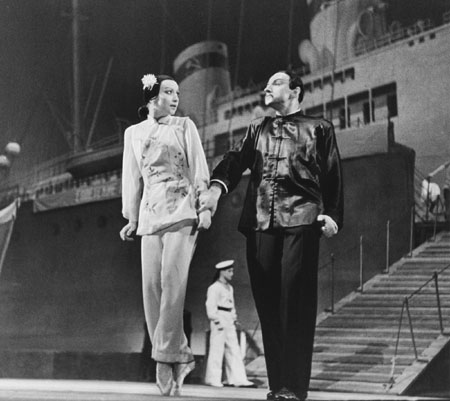

George Petrusov. Red Poppy. 1950. Tao-Khoa – Olga Lepeshinskaya, Lee Shang-Fu – Aleksei Yermolayev

George Petrusov. Red Poppy. 1950. Tao-Khoa – Galina Ulanova, Lee Shang-Fu – Sergei Koren

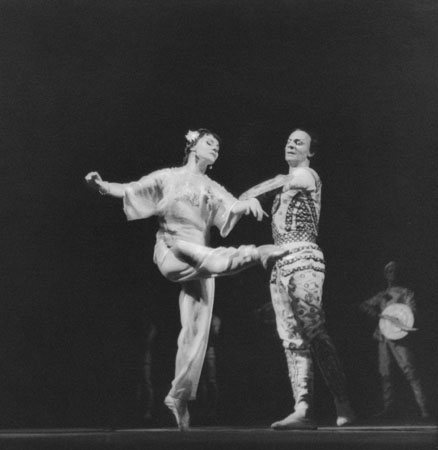

George Petrusov. Red Poppy. 1950. Tao-Khoa – Olga Lepeshinskaya, Warrior – Aleksander Lapauri

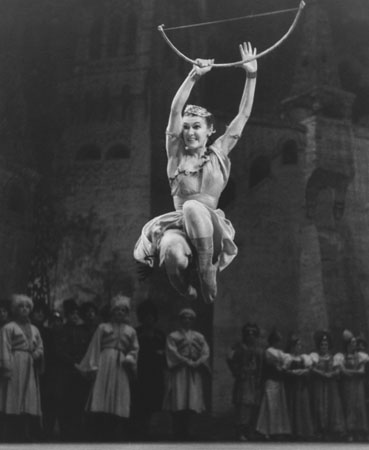

George Petrusov. Little Hunchbacked Horse. 1949. Tartar dance. Eugenia Farmaniants

George Petrusov. Little Hunchbacked Horse. 1949. Ural dance. Gleb Yevdokimov

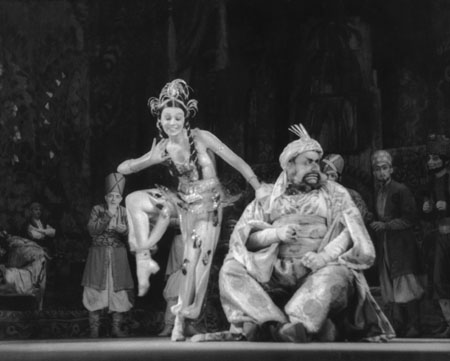

George Petrusov. Little Hunchbacked Horse. 1949. Khan – Aleksander Radunski, Khan’s favourite wife – Valentina Galetskaya

George Petrusov. Cinderella. Cinderella – Raisa Struchkova. Late 1940s

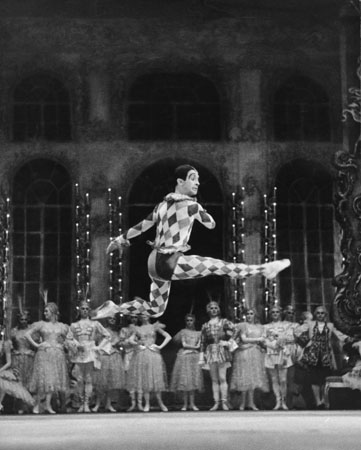

George Petrusov. Cinderella. Jester – Leonid Shvachkin. Late 1940s

George Petrusov. Cinderella. Dance of the three oranges: Tamara Tuchnina, Liudmila Ivanova and Olga Krylova. Late 1940s

George Petrusov. Cinderella. 1950. Andalusian dance: Valentina Faerbakh and Georgi Tarabanov

George Petrusov. Cinderella. 1950. Andalusian dance: Valentina Faerbakh and Georgi Tarabanov

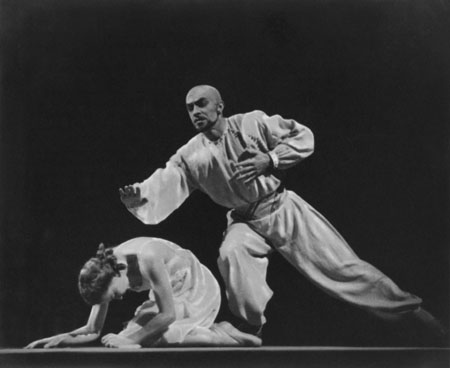

George Petrusov. The Fountain of Bakhchisarai. Maria – Galina Ulanova, Girei – Piotr Gusev. 1940s

George Petrusov. The Fountain of Bakhchisarai. Dance of Girei’s wives. 1940s

George Petrusov. The Fountain of Bakhchisarai. Nurali – Asaf Messerer. 1940s

George Petrusov. Don Quixote. Street dancer – Vera Vasilieva. Late 1940s

George Petrusov. Don Quixote. Espada – Sergei Koren. Late 1940s

George Petrusov. Sleeping Beauty. Waltz. 1940s

George Petrusov. Swan Lake. 1947. Odillia – Marina Semionova, Siegfried – Aleksander Rudenko

George Petrusov. Little Stork. 1949. Olia – Nina Chorokhova

George Petrusov. Little Stork. 1949. Olia – Nina Chorokhova, Pioneer leader – Vyacheslav Golubin

George Petrusov. Little Stork. 1949. Ostrich – Aleksei Varlamov

George Petrusov. Little Stork. 1949. Cat – Natalia Orlovskaya, Dog – Aleksander Tsarman, Rooster – Leonid Shvachkin

George Petrusov. Little Stork. 1949. Cat – Natalia Orlovskaya, Dog – Aleksander Tsarman

George Petrusov. Raisa Struchkova and Aleksander Lapauri. 1950s

George Petrusov. Yekaterina Maksimova and Vladimir Vasiliev. Early 1960s

Moscow, 14.12.2004—20.01.2005

exhibition is over

Share with friends

For the press

In the late 1940s — early 1950s a well-known photographer, whose works included pictures of the great construction sights of Magnitogorsk, of the famous «physical fitness» parades in Red Square and of the Moscow metro, unexpectedly received an important commission — to make a series of photographs for the anniversary album «The Bolshoi Theatre Ballet». Prior to this occasion, Georgi Petrusov had no experience with classical dance. The event was like an encounter of two different universes: an academic theatre, celebrating one hundred and seventy-five years since its foundation, opened its doors to an alien photographer, who became famous not as a man working with the arts, but whose speciality were the achievements of socialist economy. Petrusov visited fifteen performances and the result proved to be worthwhile both for the history of photography and of ballet dancing. Of course, the Bolshoi was photographed many times before, but it seems that never on such a large scale, which so vividly portrayed a specific historical period.

Petrusov, while working in the epoch of the first five-year plans, was heavily influenced by Constructivism with its ability to perceive an artistic image as a system of spatial elements. He was perfectly comfortable with approaching his object sideways, from beneath, from any point whatsoever. Eisenstein, Rodchenko’s colleague and contemporary, would have his Dnieper Hydroelectric Power Station, photographed from above, curve arrogantly, reminding of a man-made rainbow; while the cannons of a Soviet battleship became a live metaphor, resembling an exotic iron animal, outstretching its extremities.

Some years after, when Constructivism was long gone, a different man entered the grand halls of the Bolshoi. It were the latter years of the Stalin era, the blossoming of the compulsory Socialist Realism. Artists had no choice but to work in accordance with the style. The Bolshoi Theatre had always been something special for the country’s leadership. It served as a sort of a main gate into a vast empire and the entrance, owing to the efforts of Soviet artists, was expected to symbolise imperial strength and faithfully represent the atmosphere of the «eternal feast of labour» blessed by the famous words of the «father of nations»: «life has become better, life has become happier».

There was also a non-political reason for changing the style. Within the walls of the academic theatre Petrusov underwent a change, which happens with many Western avant-garde choreographers, who are now often invited to the Bolshoi. Finding themselves in the famous stronghold of traditions, the innovators unexpectedly witness their subconscious experiencing respectful and conservative feelings, akin to those that overwhelm you in a museum of antiquities, where the exhibits (here — ballets), covered with the dust of centuries, are all carefully numbered, listed and accompanied with a «do not touch» sign. Here, recently acquired exhibits (in our case — new performances) still resemble the rarities of bygone days. Any changes in technique, that went beyond classical and character dance, were completely banned in Soviet ballet by orders coming from the very top (formalism!), so that the heroes of the most recent history, from partisans to sailors, in Stalin’s ballets had to be content with the plastic language of the 19th century, spiced up with only a little acrobatics, i.e. imposing leaps and high support. On of Petrusov’s shots shows how, during a performance of the ballet «Little Stork», schoolgirls in white aprons and pioneers wearing red ties carefully outstretch their toes and turn out their feet, just like some classical stage naiads and dryads...

Travelling in the USSR, Petrusov was photographing a world still in the making, its spatial imagery ready to be transformed by the interference of his Leica. Working with classical ballet the artist faced a different situation: he was to represent a phenomenon which had formed a long time ago with many century-old traditions. The photographer had to connect himself to a powerful artistic organism, which, with all its conservatism, was paradoxically full of passion and was living in accordance with its own plastic laws. The young man, chasing dynamic socialist construction projects across the country, was a demiurge directly involved in creating a chronicle of contemporary history. The mature photographer, working inside the Bolshoi, left us a contemplative chronicle, reflecting an alienated view of a majestic object. These photographs have certainly the mood of looking from a respectful distance. We should also bear in mind that the theatre definitely represents a kind of magical space and classical ballet is permeated with its own enigmatic mysticism, which carries away anyone who really appreciates this art with all its seemingly «absurd» (from a realistic point of view) aesthetics and old-fashioned technique. These works also show how theatrical imagery slowly entices Petrusov, so that the initial reserved manner somewhat slacks.

Many people who owned a camera photographed and still photograph dancing, but not all of them manage to grasp the spirit of this art. As a professional, Petrusov had a perfectly clear idea of what he was dealing with. He realised the necessity to accept the canons of classical dance, its aesthetic based on frontal composition of the whole ensemble and the obligatory impression of harmony in the corps de ballet geometry. Petrusov’s works are gala photographs, reflecting the classical dance’s predilection for symmetry. His anniversary album does not include shots taken from backstage; only from the centre of the hall, from below, possibly from the first row of the parterre. At the same time Petrusov’s photographs are not retouched by gloss. Creating the album, he tried to emphasise the great artificiality of theatrical nature. His ability to analyse spatial structures, which went back to the days of his youth, helped him to see dancing also as a sort of structure, perceiving its framework, architectonics, composition of volumes and the interplay between the whole and its parts. Here, behind the official portrait, we can witness the eternal «beautiful clarity» of ballet movement. The camera «supports» the dancers; the photographs of group scenes, while fully preserving the dynamics of stage movement, simultaneously display the traditional hierarchy of classical ballet: a pyramid (corps de ballet, various soloists) crowned by the figure of the prima ballerina.

In his close-ups, Petrusov, who photographed during actual performances, often used the same technique as the famous pre-revolutionary ballet photographer Karl Fischer in his studio in Kuznetski Most Street. This was because both had the same goal — to reveal the maximum effect of posture. Since then many artists followed a similar method, which in contemporary eyes has become a cliche: to represent a leap, an arabesque or an attitude — the most striking moments of a show in terms of photography. However, Petrusov was also perfectly able to convey the unexpected turns of the mise en scene, which in each given moment depend on the mood and the mastery of the performers. The photograph of Harlequin from the ballet «Cinderella» is completely different from that of Zarema from the «Fountain of Bakhchisarai». The former is characterised by a flat rendering of space and by the shading of the stage’s depth, reminiscent of the «World of Art» style. The straight line of the corps de ballet in the background impressively stresses the grotesque «profile» leap of the soloist, while the vertical lines of the backdrop add a finishing touch to the shot. Zarema, on the contrary, is portrayed with a deliberate diagonal stress in the whole perspective: the queen of the harem, fully conscious of her beauty and power, stands half-turned towards the audience, giving an haughty look from above to her obsequious maid, bending towards her feet. One can almost recall Giambattista Tiepolo or Paolo Veronese. Raisa Struchkova — Cinderella reminds us of the girls from the elite Smolny Institute, painted by Dmitri Levitski. Or take a shot from the «Red Poppy», where Petrusov uncovers the habitual surrealism of ballet space: the tiny figure of a sailor beside the backdrop (an enormous ship) is almost trampled by the feet of the foreground figures — the main heroine Tao Khoa and the grotesquely evil Lee Shang-Fu, the negative character. The majestic Marina Semionova (the «Black Swan» and Mirandolina from the ballet «The Innkeeper» after Carlo Goldoni) is photographed in the process of diabolical coquetry with the Prince and during some no less passionate flirting with the Cavalier; the comic actor Alexander Radunski (the Khan in the «Hunchbacked Horse») is caught in an extremely wilful state, typical for a petty despot; a knight is kissing the hand of Sofia Golovkina — Raymonda, the neck of the dancer having a queenly bend to it, — the prima, her back turned towards the audience, clearly knew that she was being photographed...

The ballet of that epoch was marked by a taste for the dramatic, evident in its narrative character, abundance of «genre» gestures and other elements taken from the dramatic stage. This feature also attracts Petrusov’s attention. In the fifties dancers of the Bolshoi were very enthusiastic about passionately showing their feelings. The performers of the Moscow ballet, always famous for their acting talents, would display their emotions almost in an ecstatic fashion, thus giving additional pleasure to their audience. This period is now called by many «the golden age» of Moscow ballet and Petrusov managed to catch some of that spirit: in his work the cloaks of the toreros in «Don Quixote» are about to frantically leap into the air, while the soloist Sergei Korien is ready to strike sparks with his heels...

Petrusov’s ballet of the 1955 official album is completely in line with Soviet art of the Stalin era. It is very concrete, mundane, down to earth, standing solidly on both feet. Opening the voluminous book, we immediately strongly feel the mentality of the epoch. Funny gauze tutus that exist no more (Galina Ulanova called them «cabbage») or the robust figures of the female dancers (impossible to imagine on stage today) instantly provoke nostalgia in the hearts of the lovers of «authentic» ballet. But in other photographs, not included in the album, we can see a different Petrusov, who, rather than focusing on the dance technique, managed to grasp some of that famous ephemeral spirit, the «sylph» nature of classical dance. It was this plastic «languor», along with the fashions coming from court and village dances, that made possible the appearance in the early 19th century of such great romantic ballets as «La Sylphide» and «Giselle». Galina Ulanova — Maria («The Fountain of Bakhchisarai») resembles a weightless curved thin reed. For Struchkova, dancing in a concert performance with Alexander Lapauri, the photographer used some lighting effects, «catching» with his camera the ray of a floodlight, playing with half-tones. The light creates a lyrical mood, immersing the male dancer in the darkness and, on the contrary, emphatically but tenderly bringing the ballerina out of it. Another photograph shows a female dancer bending down to fix her points, just like in Edgar Degas’ paintings, who managed to discover for other artists the expressiveness of ballet working postures. Then there are other portraits: Alexei Yermolayev — Philippe from «The Flame of Paris», with his mask of a hero obsessed with an Idea. And a later shot, of the early sixties, made outside the theatre and in informal circumstances, at the home of Yekaterina Maksimova and Vladimir Vasiliyev. A tube radio, the loving glance of a young husband and a partner, the «babette» hair style of the youthful Katia, engaged in routine ballet work — stitching her points... Nothing official, no make-up and no rules of the game, so that for some reason one tends to think that here life made a leap from the realm of necessity into that of freedom.

Maya Krylova