A CONSUMER’S DREAM

Nina Sviridova and Dmitry Vozdvizhensky. In the Sun next to Detsky Mir Department Store. Moscow. 1961. MAMM/MDF

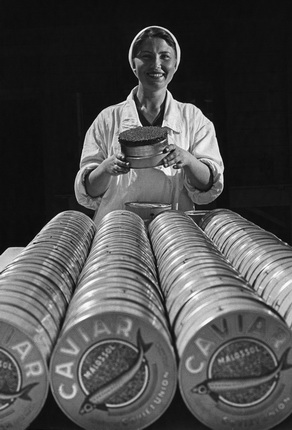

Lev Borodulin. ‘Everything for the People!’. 1960s. MAMM/MDF

Dmitry Baltermants. At a Shoe Store. Moscow. 1954. Private collection

Alexander Abaza. ‘Alcohol Has Arrived’. Anadyr, Chukotka. 1985. MAMM/MDF

Boris Ignatovich. Home Flower Delivery. Moscow. 1934. Private collection

Semyon Mishin-Morgenshtern. Fur Department. 1950s. MAMM/MDF

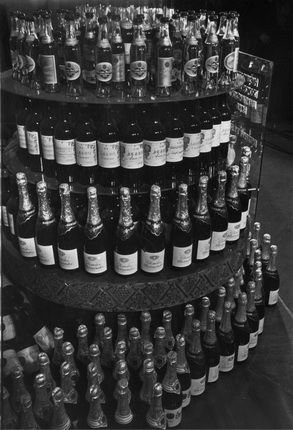

Unknown author. The first batch of Soviet champagne. Moscow. 1937. Private collection

Unknown author. Festive Decoration of Passazh Store on Nevsky Prospect on the Occasion of International Cooperation Day. Leningrad. 1925. Private collection

Alexander Sigidin. Waiting. Dnepropetrovsk, Ukrainian SSR. 1980s. MAMM/MDF

Vsevolod Tarasevich. In the Yeliseyevsky Food Market. Leningrad. 1966. MAMM/MDF

Robert Diament. Before a Store Window. 1954. MAMM/MDF

Exposition view

Exposition view

Exposition view

Exposition view

Exposition view

Share with friends

Curators: Sergey Burasovskiy, Anna Zaitseva

Exhibition shedule

-

18.12.2015—24.02.2016

Moscow

Multimedia Art Museum

-

22.03.2017—2.07.2017

Nizhniy Novgorod

Federal Center of Contemporary art

-

13.07.2017—3.09.2017

Ulan-Ude

National museum of Buryatiya republic

-

21.09.2017—26.11.2017

Irkutsk

Victor Bronstein Gallery

-

20.12.2017—25.02.2018

Yekaterinburg

Yeltsin–Center

For the press

‘A Consumer’s Dream’ provides an excursion into the history of shortages in the USSR and correlations between scarcity and advertising in Russia from the late 1910s to mid-1990s.

By 1918 the effects of the First World War, October Revolution and Civil War meant that a country already in ruins was confronted by acute shortfalls in food, clothing, everyday items and essentials.

The New Economic Policy or NEP relieved the problem of shortages to some extent, but only temporarily. Consumer deficits were not fully resolved until the mid-1990s, with abolition of the planned economy and the introduction of free trade in the new Russia.

Advertising was a paradoxical phenomenon in a society stricken by shortage: the dilemma was not how to increase demand, but finding the means to satisfy demand. For Soviet citizens every consumer item, even basic necessities, became the subject of their dreams. Each item had to be ‘obtained’, and for that to happen it was not enough to work and earn wages. In pursuit of this ‘dream’ people had to swop galoshes for lengths of cloth, cloth for vacuum cleaners... These were replaced in turn by scarce books, then theatre tickets, fridges and automobiles...

Soviet advertisements did more than simply display books or toothpaste, galoshes and mayonnaise, fruit juice, sparkling wine and black caviar, vacuum cleaners and floor polishers, televisions, cars and, of course, Soviet perfumery. Each advertising poster was obliged above all to create the image of a contented society with an abundance of goods, confirming the primary Soviet slogan, ‘Life has become better, life has become happier!’

The photographs in this exhibition reflect changing times in the USSR, from the beginning to end of the 20th century. They were taken by renowned Russian photographers such as Alexander Rodchenko, Arkady Shaikhet, Boris Ignatovich, Vsevolod Tarasevich, Dmitry Baltermants, Viktor Akhlomov, and many others. Also featured are posters by outstanding Soviet artists, including Alexander Rodchenko.

This exhibition is equipped with numerous screens showing scenes from the classics of Soviet cinema, where the ‘consumer dream’ became a recurring theme. These are the legendary films of Boris Barnet, Georgy Alexandrov, Konstantin Yudin, Eldar Ryazanov, etc.

The exposition is supported by articles from everyday Soviet life, on loan from the Moscow Design Museum: Soviet toys, hats and ladies’ shoes, bottles of highly sought-after perfumery, the KVN television, carefully preserved black caviar jars and even the ‘imported’, patched jeans of famous photographer and journalist Yuri Rost.

Dreams displace reality in the exhibition, just as they did in the Soviet Union, and the final chapter devoted to the 1990s shows how shortages disappeared as the new market economy finally eclipsed the dream.