Closer to the body. Russian costume in photographs XIX — XXI centuries

Dmitri Baltermants, Sergey Borisov, Unknown author, Alexander Rodchenko, Leonid Shokin, Sergey Leontiev, Alexey Mazurin, Alla Solovskaja, Jury Abramochkin, Vlad Monroe, Oleg Kulik, Alexander Petlyura, Sergei Lobovikov, N.M. Mogiliansky, W. Carrick, T. Mitreiter, V. Plotnikov, N. Edenmont

Sergei Lobovikov. Beauties, Vyatka region. 1914–1916. A. Loginov collection

W. Carrick. From the Russian Types series, St. Petersburg. 1860s. A. Zlobovsky collection

W. Carrick. Russian Types, carters in a St. Petersburg tea-room. Late 1860s. A. Zlobovsky collection

N.M. Mogiliansky. Three girls (cousins), Novosilsky ditrict, Tula region. Expedition photograph. 1902. The Russian Museum of Ethnography collection

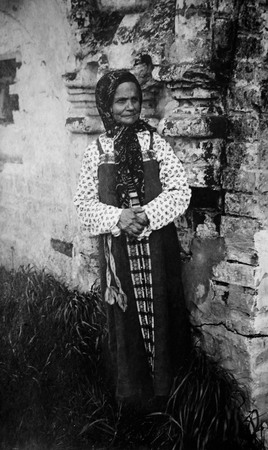

T. Mitreiter. Peasant woman in richly adorned antique costume, Kostroma region. 1870s. The Russian Museum of Ethnography collection

Alexey Mazurin. Boys’ dance, Moscow region. 1890s. From the Russian State Library collection

Unknown author. Kursk region peasant costume from N.Shabelskaya collection. Late 19th - early 20th century. A. Zlobovsky collection

Unknown author. Arkhangelsk folk-tale narrator and singer Maria Krivopolenova in Vologda. 1913. The State Literature Museum collection

Leonid Shokin. Dance, Kimry village, Tver region. 1916. The Moscow “Moscow House of Photography”

Unknown author. V. Petrova-Zvantseva (Lyubava), “Sadko”, Novgorod bylina by N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov, S. I. Zimin Opera Theatre, Moscow. 1912. The A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum collection

Unknown author. V. I. Kachalov (Berendei), “The Snow Maiden” by A. N. Ostrovsky, Moscow Arts Theatre. 1900. The A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum collection

Unknown author. Chorus artist, “Sadko”, Novgorod bylina by N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov, S. I. Zimin Opera Theatre, Moscow. 1912. The A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum collection

Dmitri Baltermants. Nikita Khrushchev from the “Six General Secretaries” series. 1955. The Moscow “Moscow House of Photography”

Alexander Rodchenko. Art critic Tatyana Malyutina, wife of artist Sergei Malyutin brother, wearing Kaluga peasant costume, Moscow. 1938. A. Rodchenko Archive

Alla Solovskaja. Vera Vassilievna, Prudki village, Krasnogvardeisk district, Belgorod region. 2005. Artist collection

Sergey Leontiev. From “Faces of the Volga”. 2003. Artist collection

Unknown author. Emma Tsesarskaya (Aksinya), “And Quiet Flows the Don” by O. Preobrazhenskaya and I. Pravov, Mosfilm. 1930. Mosfilm Archive

Jury Abramochkin. Satirical fashion theatre with Vyacheslav Zaitsev on the left. 1960s. Artist collection

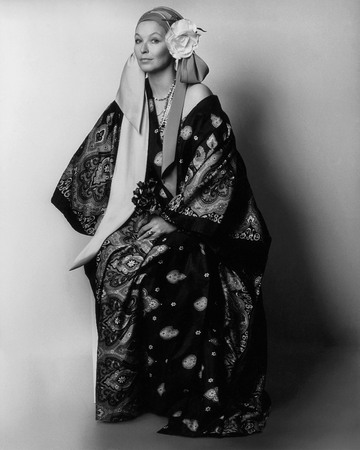

V. Plotnikov. Marina Vlady wearing a dress by V.Zaitsev, Moscow. 1975. Artist collection

Sergey Borisov. After Bathing. 1994. S. Burasovsky collection

Alexander Petlyura. Maize Field. 1993. Artist collection

Oleg Kulik. Tolstoy and Hens, installation. 2004. Artist collection

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monro. Is It Warm for You, Girl? 1997. The Moscow “Moscow House of Photography”

N. Edenmont. Heirloom. From the “Still Born” project. 2008. Courtesy Aidan gallery

Moscow, 17.04.2009—10.05.2009

exhibition is over

Na Solyanke Gallery

109028, Moscow, 1/2, b. 2 Solyanka st. +7 (495) 621-55-72, е-mail: solgallery@yandex.ru

Share with friends

Curator: Anna Petrova

Presented by the Museum “Moscow House of Photography”, Russian State Art Library, State Literature Museum, Central Theatre Museum A. A. Bakhrushin, Concern “Mosfilm”, Russian Ethnographic Museum

Supported by MasterCard Selection

For the press

Clothes are man’s ‘second skin’, an everyday necessity, a work of art, a projection of identity, a political weapon, retail merchandise, a means of seduction, the subject of photography...

National dress or folk costume is a fascinating historical phenomenon that exists by its own specific logic and has a distinctive structure and palette, that is stored in museums and collections, reconstructed and recorded in millions of photographs. This project is a photographic digest of Russian folk costume: from ethnographic photography till contemporary art.

First developing in the 12th to 13th centuries, traditional Russian costume was worn by tsars and grand dukes, boyars and merchants, craftsmen and peasants until the early 18th century.

In traditional culture the female silhouette was formed by rectangular skirts or ‘ponyova’ (southern Russia) and the triangular-trapezoid dress or ‘sarafan’ (northern Russia). In both northern and southern Russia male costumes were far simpler and more uniform than their female counterparts: a ‘kosovorotka’ shirt with side neck-fastening was belted round the underbelly and worn outside narrow trousers tucked into boots.

The form of the costume (proportion, gamut of colours) was naturally suited to the wearer and selected for a particular anthropological type: the fair-haired, light-eyed northerners preferred a festive costume in pastel shades with an elongated shape, while southerners with dark hair and eyes favoured a colour scheme of contrasting red, white and black.

Peter the Great’s rise to power heralded a period when costume was controlled by ‘political censorship’. Urban clothing according to Western European style was introduced to Russia by special decree in 1700. Catherine the Great maintained these clothing restrictions, but it was during her rule that ‘Russian fashion’ first emerged. According to court etiquette (1782), on certain festivals ladies were obliged to appear at court in a ‘Russian gown’ — a sarafan with a corsage and skirt.

The next ‘Russian fashion’ vogue was related to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. By this time red and blue Empire-line Russian sarafans were worn in Europe. Nicholas I introduced a new gown complete with ‘kokoshnik’ for wear at court (1834), and in the reign of Alexander III senior military ranks adopted a uniform with features of the ‘Russian style’.

From the second half of the 19th century to the early 20th century garments in the so-called ‘pseudo-Russian style’ were widespread in large towns. This consisted of dresses or skirts and a bodice adorned with factory-made braid and lace instead of hand-stitched embroidery. The entire ensemble was embellished with ribbons, beads, kerchiefs and other accessories reminiscent of peasant folk costume. Wet nurses and nannies employed by rich families wore a ‘kokoshnik’ and sarafan which became their ‘professional’ outfit, a kind of uniform.

When photography appeared in Russia in the mid-19th century it quickly became one of the most effective means of documenting the way people lived, giving rise to the numerous postcards and albums distributed all over the world that illustrated so-called ‘Russian types’, everyday life and genre scenes, or portraits of peasants in national costume.

After the trauma dealt by political reforms Russian costume was reanimated by Russian art: no longer a historical reality, it became a cultural symbol. Tales of ordinary folk from Pushkin and Bazhov, Ostrovsky and Sholokhov became classics and were adapted for the theatre and cinema. ‘Types’ evolved into characters photographed by the main Russian photo ateliers wearing costumes devised by Vrubel and Bilibin... In the 20th century photogenic national dress was visualised by the cinematographer in historical films, comedies and folk-tale adaptations... Film studios amassed hefty albums of screen tests, while magazines, postcards, bills and posters circulated in huge print runs.

Haute couture first saw the light in the 1860s. Fashion acquired the status of an art form that found its way into museums, and demonstrations of new models were reconceived as a show or performance. Man Ray began taking photographs of fashionable clothing; later Tracey Emin advertised designs by Vivienne Westwood, as did Cindy Sherman for Comme des Garçons. In Russia Valery Plotnikov photographs Slava Zaitsev’s new creations and the Application studio works with Tatyana Parfyonova. Soviet amateur and light entertainment made use of ‘folk’ motifs and themes, at times reducing them to kitsch. This kitsch is unmasked and turned inside-out in contemporary art, in which Russian folk costume becomes an attribute of performance and installation.

Photography ‘recalling’ the art of Venetsianov and Vasnetsov and replicating the poses and gestures selected by painters and graphic artists returns the debt: paintings, watercolours and illustrations are taken from postcard photographs. By experimenting with the colour palette and with light and optical effects while using subjects to the best advantage and selecting the models, photography creates an original ‘world picture’ and offers its own view of reality.