The elevated view of a city cradled in a seemingly infinite landscape. The urban context is clearly visible in the foreground. The viewpoint is lowered slowly from the horizon to the buildings and we begin to zoom in on them. Floating gently, the camera smoothly tracks onward. After a few crossfades, it homes in on a building and its solitary open window. It gradually draws closer and finally enters the darkened room▓s interior through a gap beneath the lowered blind. After a short while two people come into view, pausing quietly for a moment until the action commences.

When Alfred Hitchcock directed Psycho in 1960, he made use of several camera settings in order to create the effect of a flowing movement between edits. What you remember from this constructed panning effect is the apparent weightlessness of the camera and its slow but gradual movement into the heart of the action. The artificial vantage point provides us with an unusual panoramic view ahead of the long tracking shot, which will finally place us in the microcosm of a room and allow the drama to unfold.

The adoption of such a viewpoint aimed at embedding an object in its environment is a much practised, descriptive procedure in the history of painting and subsequently in photography, too. The deployment of large-sized cameras -151; usable only in conjunction with a tripod -151; coupled with the low sensitivity of the film, meant that it was initially not possible to depict actual movement. Conversely, the portrayal of landscape was possible, practically without any limitations whatsoever, apart from the fact that the film stock of the time was still unsuitable for the simultaneous and well-defined depiction of both sky and landscape. Nevertheless, atmospheric works were developed in the middle of the 19th Century due to the endeavours of photographers such as Gustave Le Gray, who created their portraits in the darkroom with the aid of several negatives. His study Brick au clair de lune from 1856/57, depicting a sailing ship on the ocean at night, was a combination of separate exposures of the sea and the sky. Although we can interpret the image as a document of an existing set of circumstances, upon closer inspection however, we discern that what we are actually dealing with is a skilfully assembled montage. We find ourselves in the paradoxical situation of trusting the photograph to be a faithful record of a concrete event, but conversely recognizing it as a construct and as such, questioning its veracity.

We find ourselves confronted by a similar contradiction when contemplating photographs taken by Bernd and Hilla Becher. Their individual images of industrial objects -151; compiled to create typolologies -151; permit horizontal, vertical or diagonal interpretation according to their arrangement. When viewed comparatively, what emerges from this miscellany of anonymous utility structures is a panorama of architectonic elementary forms based upon the principle of repetition and variation. Although the photographs have all the objective, sober appearance of illustrations in a text book, concealed behind their neutral facade lies their creators▓ obsessive passion for the exhaustive cataloguing of forms from the selected branch of industrial buildings, which, according to the Bechers, provides an -147;optimal mean-148; in keeping with their respective artistic sensibilities. The standardized processing of the black and white photographs makes it impossible to detect the fact that the individual images derive from a typology comprising different countries and, moreover, different periods during the many decades of their artistic endeavour. In this way both geography and the passage of time are concentrated into a combination of images. Viewed from a distance, these typologies show basic geometric forms -151; circles, rectangles and cylinders.

By contrast, closer scrutiny reveals detail of these images permeated with all manner of information, thus offering different types of reception. Removed from their actual context, Bernd and Hilla Becher▓s typologies document particular phases of industrial culture, but at the same time they are concerned in a romantic sense with the phenomenon of change and loss.

Andreas Gursky▓s work can be described by many of the salient criteria and reaches out beyond them during the course of his development into an area of contemporary photography, which is yet to be adequately defined. The artist▓s early photographs often evince topographical layering. In these cases the photographer has adopted readily intelligible viewpoints in order to show the motif in its contextual setting. We normally discover a detail in these panoramic shots, which elicits our attention. The composition is geared towards classical patterns of design. The images are unusual because of the atmospheric lighting conditions and the majestic effect of the landscape, which often contains the evidence of a human presence in miniature. An alpine summit swathed in mist. The gondola of a cable car, shifted slightly towards the centre of the picture. The Niagara Falls. Shrouded in spray, a tiny boat full of tourists approaches the massive waterfall. Riparian landscape with angler. Unrecognizable as individuals, these figures form the key toward an understanding extending beyond the pure representation of landscape.

The diminutive scale of their depiction prompts us to view them not as protagonists, but rather as our intrepid representatives forced to prevail against a seemingly overwhelming natural world.

Andreas Gursky▓s design for these photographs places him in the tradition of the -147;decisive moment-148; -151; i.e. the illustration of the climax of an activity, which, in symbolic attenuation, represents the whole and therefore characterizes it - as defined by the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. Photographers working in the traditional way capture this moment by using their knowledge of the material, by being in the ideal position and by releasing the shutter in the right moment. In this way the gondola, the boat and the angler are in the right place at the right time for the perfect, formal framing of the composition.

At the time these photographs were taken, the use of colour was not self-evident as is the case nowadays. By the mid-eighties however, Germany had managed to catch up with a movement already established in the USA by introducing colour processing machines to educational establishments, thereby enabling students to produce their own prints. Two decades earlier, photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz, William Christenberry and Stephen Shore had themselves discovered colour photography as an artistic medium of expression. However, it was not until William Eggleston▓s solo exhibition Color Photographs in New York▓s Museum of Modern Art in 1976 that colour photography finally received recognition as an artistic medium in its own right. The reason for this was mainly because the American photographer Eggleston did not use colour exclusively to describe his chosen motifs, but rather, by discovering the technique of dye-transfer, he was able to intensify and dramatically heighten the individual colours of his prints to such an extent that a second layer of viewing became visible behind apparently everyday motifs, facilitating additional psychological interpretation. Nowadays such an effect can be achieved by the use of digital image processing. When Andreas Gursky describes his new images of an Asiatic island landscape as eerie and somehow threatening, then this atmosphere is not only brought about through the strange impression given by the nexus of motifs, but also through the pointed use of colour.

At the beginning of the 1980s there was the additional possibility of producing large format prints in colour. The Canadian artist Jeff Wall had already presented his large-scale transparencies mounted on light boxes, and in so doing had transferred a commercial method of presentation to the field of fine art. His images demonstrated scenes he had once observed, then later recreated with actors under his direction, arranged and duly photographed. Gunther Forg framed his monumental architectural photographs, which he took in the style of the new way of seeing from the 1920s, behind glass. The resulting reflections give rise to intentionally confusing and disturbing effects depending on individual perspective, permitting different ways of viewing the photographs. Despite their wholly different strategies, the works of both artists elude one-dimensional documentary interpretation and are transferred as such to the realm of the pictorial. Furthermore, the unusually large formats of the works engender a more physical experience when viewing them. The physical presence of the images alone changes the way they are received. The fact that one▓s entire perspective is filled when stepping up close to the picture results in an unusual viewing experience and the feeling that one is being engulfed by the image.

The students attending the Dusseldorf Academy where Bernd und Hilla Becher taught, likewise started to enlarge their colour photographs beyond the usual dimensions. They were conversant with the formats of the Becher typologies, which had been created through the combination of individual photographs, and were also keen to explore the dimensions of panel painting. Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Axel Hutte and Andreas Gursky all chose unusually large formats for the time.

The special elaboration of their works, which involved a process that lent the motifs an unusual presence through the combination of the print and Perspex, was largely instrumental in their being perceived as perfect presentations of contemporary import. The majority of photographers at the time had ignored this aspect. It became thus an established tradition to send prints to the exhibition venues where they were mounted and placed in available frames and displayed according to the respective ideas of those responsible. The photographers believed in the power of their images and trusted that they would prevail in whichever form and context. Michael Schmidt -151; who taught Gursky (among others) in Essen for a short time -151; was also instrumental within the field of photography with his book and exhibition project Waffenruhe from 1987 in pushing through installation as a form of presentation for respective exhibition situations and establishing thus a subjective and therefore, altogether new pictorial understanding for a form of documentary photography.

Whereas photographs at this time were all produced the traditional way, that is to say via an analogue procedure, the advent of digital image processing meant that a technical development had come into play, which enabled images to be altered at will. If the classical photographer is, technically speaking, directly and inseparably connected to his motif, digital post-production now offered the possibility of liberation from this dependency. The photographer working traditionally proceeds subjectively, that is to say when taking the photograph he designates a section, which will then represent the whole.

As in the case of painting, digital processing allows an accretional method of working, which means not only the possibility of fashioning colours individually, but also that individually photographed elements can be brought together to compose a new image.

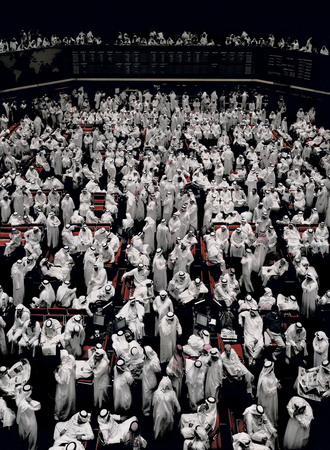

Andreas Gursky has applied this method during the past fifteen years and has arrived at a series of images that disengage from their representational purpose and posit a new artistic ideal. In so doing he has created both radically empty works and, by contrast, constructions, the sheer opulence of which is unique in the history of photography. The compositions extend from a central starting point and reach out beyond the borders of the image, apparently stretching to infinity in certain cases, proffering multiple ways of seeing. From a distance we perceive a formal macrostructure: an arrangement of colours, the use of contrast and often an ornamental design. On approaching the image and upon closer scrutiny, a flickering microcosm of detail reveals itself to us. Should our gaze from afar be subtly guided by a detail, we are confronted close-up by a bounteous offering of possibility and discovery whose connections we forge for ourselves, thereby detecting an abundance of narrative content. We become active, equal partners with the artist. The primary aim is not the rapid consuming of these images, attractive though they may be at first glance, but rather the decelerated reception and more profound understanding on a pictorial and contextual level. It is all about an experience of the world based upon the foundations of seeing.

The image of one of Madonna▓s concerts illustrates different, temporally sequential elements of the American singer▓s spectacular stage show unified in a single composition.

The entire course of the concert is reproduced in condensed form in the shape of an apparent snap shot. Whereas a photographer working in the classical tradition captures the climax of an event and can only reproduce the complexity of the action in the form of a series, in this case several different layers inform the digital design of the image; thus the classical, decisive photographic moment loses its validity and can only exist as a construction.

The scope of the digital possibilities on offer leads many artists to design their images completely in keeping with their own ideas. Everything is planned; the works are controlled right down to the last detail. The results often seem like fanciful illustrations from a series of individual, emotional worlds. Although these works have the power to make us stagger in wonderment on account of their sheer abstraction and artifice, they nevertheless seem lifeless in a strange way. Their half-life is consequently limited, sharing a similar fate to the leaves of a calendar quick lose their significance and allure. By contrast, photographs produced the traditional way can keep us fascinated for a long time, not only by duplicating the visible world, but also by positing a gentle incongruity between the object and its image. By means of the shifting of perspective through which a new way of seeing familiar motifs emerges, these photographs can indeed have a residual effect upon us. A salient factor here is chance itself, which photographers accept in order that they, by way of the unexpected, may do justice to the complexities of reality with their images. Andreas Gursky combines the freedoms of digital design with the binding qualities of traditional photography. In this way he also accepts chance as an enriching element in individual shots, which may later become part of the composition in the form of a section of the image. The incalculable nature of these details disrupts the perfection of post-production, rendering the images accessible to us once more and opening them up for our free play of associations.

Andreas Gursky has taken a lot of photographs at Formula 1 races in recent times and his pit stop shots en masse add up to a dramatically charged moment for the respective technical teams locked in competition. The scale of the protagonists here is larger than it is in other works and their intricate choreography in conjunction with the stage-like lighting and the hordes of spectators in the background, lend the images immense dramatic tension. Whereas there was often only a solitary person depicted in Andreas Gursky▓s early photographs, in the majority of his later works the individual is exclusively part of a mass of people, which is itself a component of larger, more elaborate scenes. These images were taken and reproduced using analogue methods and cohere with the rules of classical composition. In his digitally composed images, the artist frees himself from this form of composition and creates altogether new spatial contexts. The proportions of buildings and landscapes can be altered as well as those of the protagonists in the swirling masses of people in order to render the design of the image more concentrated.

The use of digital processing also renders the transition between a motif▓s individual elements so fluid that seemingly familiar vistas are created, although in reality they do not exist quite in that way. The works are fictions based upon facts. Statement and proposition, representation and idea are united thus in one image.

The artist has used a viewpoint in the majority of his new photographs, which we can no longer reconstruct. Andreas Gursky does indeed photograph many starting shots -151; subsequently to be composed on the computer screen -151; from an unusual vantage point we would not normally be able to adopt. A kind of artistic perspective emerges in conjunction with the digital construction, which no longer follows the optical rules of photography and in consequence confuses us, because the motif is presented in a variety of layers simultaneously. And yet the world in Andreas Gursky▓s photographs appears ordered and accessible to us. When observing the images we have the feeling of weightlessly floating over the motif, its panorama unfolding before our very eyes. The privileged perspective constructed by the artist not only allows us to discern complex connections within one composition, but also to perceive the objects in an ideal-typical guise normally denied us. In his most recent photographs from North Korea, the design is generated from motifs from the staging of live images; as a result of this phenomenon we are given to comprehend the mass of troops as a symmetrically ordered representation of the apparently absurd legitimation of a now obsolete totalitarian political system.

When the German photographer August Sander set out to compile a typology of the

Weimar Republic in the 1920s with the aid of portraits -151; that is to say create an analytical cross-section of society using photography as his medium -151; he worked with portraits of people assembled in portfolios. Picture after picture was intended to exemplify the social core of the times in a prototypical fashion. In Andreas Gursky▓s case, instead of a serial, juxtapositional arrangement of the images, many of the photographs find their way into the final composition by providing new meaning in the sum of their compositional parts. As distinct from the Bechers▓ -147;optimal mean-148;, Andreas Gursky does not work with the lowest common denominator, but with extremity instead. The world seems intelligible in his pictures because even when chaotic, it still appears to have been designed. Posited in our minds is the suggestion of a ready availability and intelligibility, which do not exist in reality and are the result of the artist▓s personal construction of authenticity.

The popularity enjoyed by Andreas Gursky▓s images in recent years is of course derived from the overwhelming radiance they possess, but it has also to do with this form of accessibility. The world of motifs in these artworks refers to the visual coding of communal experience. For although it used to be held that collective memories were connected both to a specific generation and cultural field, nowadays one doesn▓t need to experience them directly, as they can be communicated medially. The incipient familiarity in Andreas Gursky▓s pictures, which we often experience at first glance, derives from the knowledge of situations and scenes stored away in our unconscious minds. In accordance with this, the works interpret collectively shaped, internal images of a global community, which draws upon a host of similar experiences and related associations. They testify to the homogenization of our consciousness and utilize the normative effects of globalization, i.e. the international standardization of our ways of living and working. The motifs are accentuated by means of their artistic interpretation, intensified to the extreme and duly transformed from mimetic representation to an individually developed and artistically posited idea of the world.

In an interview towards the end of his life in the late 70s, the American photographer

Walker Evans differentiated between documents -151; e.g. police photographs of a crime scene -151; and his images as photographs in a documentary style, and in so doing laid down an enduring definition for the artistic application of the medium in its documentary form.

Walker Evans▓ view of the world comprised photographs taken according to artistic criteria and at the same time personally filtered documents. His photographs from the late 1930s of the impoverished, rural inhabitants of America▓s Southern States, afflicted by the dual blight of economic depression and drought, are now regarded as icons of the period, contributing in exemplary fashion to an understanding of this epoch of American history.

Like Walker Evans before him, Andreas Gursky trawls his contemporary world for visible phenomena that can explicate the past in the shape of an image formulated in the future.

He has dealt with the themes of his day from the outset of his career as an artist and has engaged with internationally significant phenomena. The themes of his images focus upon work, leisure, presentation and representation. His works on the production and distribution of goods, as well as high-tech factories and international stock exchanges, large-scale gatherings such as concerts, sports events and aspects of mass tourism, representational architectural buildings and the presentation of consumer items, from luxury goods through to supermarket products, can be duly allocated to any of these categories. This impressive panoply also includes the more negative aspects of the capitalist system, such as working conditions, factory farming of animals, the abuse of the environment and the phenomenon of -147;consumer terrorism-148;. Andreas Gursky never treats these topics superficially or in a moralizing way. Distinct from photojournalism, predicated as it is upon the sensationalism of the single image and shock element, Andreas Gursky, even in his more critical works, endeavours to leave his view of the world open to our interpretation, both in terms of its objective content and its seductive form. With the apparent ease of a stroll through the global park, the relevant individual images collectively convey to us an analysis of our contemporary condition and open up thus a view into the future.

In contrast to conventional photography, the authenticity of digitally produced photographs cannot be unequivocally attested in its images. Although Andreas Gursky▓s works have been composed using the symbolic language of immediate, direct photography, they nonetheless deftly integrate the characteristics and qualities of both forms of photography. The new definition of the documentary concept in this field of digital composition could then refer to the credibility of the works in question: is there any concurrence between the artist▓s imagination inherent in the images, in the composed and constructed testimony to his experiences, and the collective associations and memories of the viewer?

If this is indeed the case, then we are dealing with images endowed with the power to formulate communal experience and ideas about the world, which in turn can also be regarded as a new form of documentation: as signs of their times, as composite constructions seeking to do justice to a highly complex reality and at the same time combining analytical observation with the pure delight of seeing. It is on the basis of this paradox and concomitant integration of painterly and medial qualities into the photographic image that the artist Andreas Gursky is able to tread new ground with his ideal-typical, compositional motifs.