Aleksandr Rodchenko

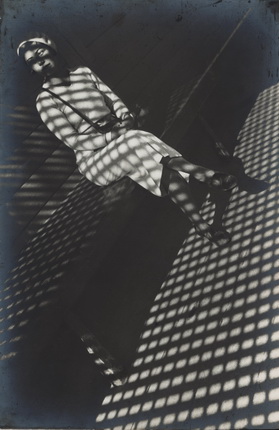

Alexander Rodchenko. Fire Escape (with a man). From the series “House in Miasnitskaya St”. 1925. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodtschenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Girls with Kerchiefs. 1935. Vintage Print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Lily Brik. Portrait for the Poster “Knigi”. 1924, Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Pioneer- trumpeter. 1930. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

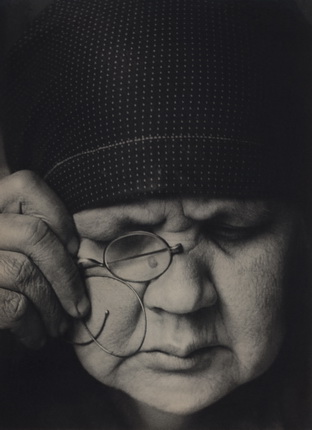

Alexander Rodchenko. Portrait of the Artist’s Mother. 1924. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

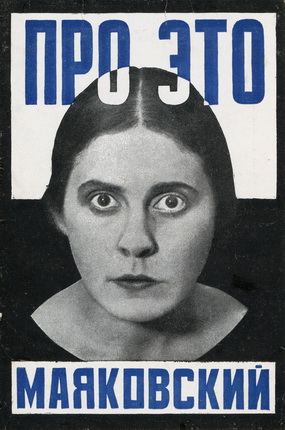

Alexander Rodchenko. Cover of the book “About That” by Vladimir Mayakovski. 1923. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

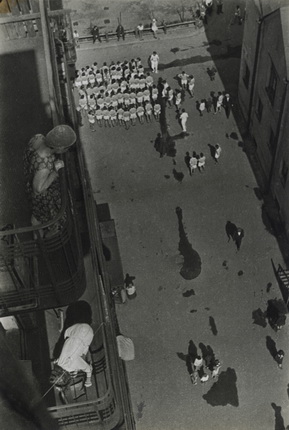

Alexander Rodchenko. People Gathering to Take Part in a Demonstration. 1928 (1933). Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

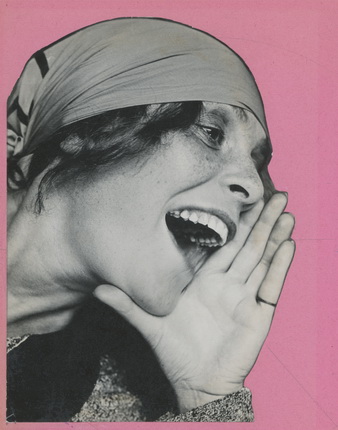

Alexander Rodchenko. Girl with a Leica. 1934. Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodchenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Alexander Rodchenko. Stairs. 1930, Artist print. Collection of the Moscow House of Photography Museum. © A. Rodtschenko – V. Stepanova Archive. © Moscow House of Photography Museum

Lugano, 27.02.2016—8.05.2016

exhibition is over

Museo d’Arte al LAC

Piazza Bernardino Luini, 6

www.luganolac.ch

Share with friends

Curator: Olga Sviblova

For the press

The Russian avant-garde of the twentieth century is a unique phenomenon not only in Russian, but in world culture. The amazing creative energy accumulated by the artists of this great age is still providing nourishment for artistic culture today and all who have dealings with the art produced by Russian Art Nouveau. Alexander Rodchenko was indisputably one of the main generators of creative ideas and the general spiritual aura of the age. Painting, design, theatre, cinema, typography and photography, all areas invaded by the powerful talent of this strong, handsome man, were transformed, opening up radically new paths of development.

The early 1920s was an «intermediate age», to quote Viktor Shklovsky, one of the finest critics and theoreticians of the day, a period when, albeit briefly, illusively, there was a resonance between artistic and social experiment. It was at this time, 1924, that photography was invaded by Alexander Rodchenko, already a well-known artist with the slogan «Our duty is to experiment» placed firmly at the centre of his aesthetic. The result of this invasion was a fundamental change of ideas about the nature of photography and the role of the photographer. Conceptual thinking was introduced into photography. Instead of just being the reflection of reality, photography also became a device for the visual representation of dynamic intellectual constructions.

Rodchenko introduced Constructivist ideology into photography and developed methods and instruments for applying it. The devices discovered by him spread rapidly. They were used by pupils and like-minded practitioners, as well as aesthetic and political adversaries. The use of the «Rodchenko method», which included the diagonal composition, discovered by him, as well as foreshortening and other devices, did not automatically guarantee the artistic dimension of a work, however. The practice of Rodchenko the photographer was confused not only and not so much by the formal devices for which he was so mercilessly criticised in the late twenties, as by the profound inner romanticism characteristic of him even in his student years. Suffice it to recall the make-believe letters he wrote to Varvara Stepanova in the early years after they met. This romantic element, embedded in the childhood which he spent back-stage in the theatre where his father worked, was transformed into the powerful utopian thinking of Rodchenko the Constructivist, who believed in the possibility of a positive transfiguration of the world and mankind.

In the 1920s in each new photographic series Rodchenko set new tasks and produced manifestoes on what photography and life would be like after they had been transformed by the Constructivist artistic principle. In the 1930s, particularly towards the end, exhausted by criticism and persecution, he tried to analyse life and artistic practice, his own included, the evolution of which was determined largely by the developing aesthetics of socialist realism. Incidentally, in the whole history of Russian photography of the first half of the twentieth century Alexander Rodchenko is the only person who, thanks to his printed articles and diaries, left unique records, artistic reflections by a photographer-thinker who witnessed historical cataclysms, which generated within him a tragic conflict of conscious premises and the unconscious drive to create.

Tired of the constant revolutionary transformations that produced a reality far from the ideals which had inspired his early period of creativity, he wrote in his diary on 12 February 1943: «Art is service of the people, but the people are being led goodness knows where. I want to lead the people to art, not use art to lead them somewhere. Was I born too early or too late? Art must be separate from politics ...»

In the final years of his life, betrayed by friends and pupils, deprived of the right to work and earn his living or take part in exhibitions, expelled from the Union of Artists, and in very poor health, Alexander Rodchenko was nevertheless a very fortunate man. He had a family: his friend and comrade-in-arms Varvara Stepanova, his daughter Varvara Rodchenko, her husband Nikolai Lavrentiev, his grandson Alexander Lavrentiev and his family, a small, but very close-knit clan charged with creative energy. If it had not been for this family Russia’s first photographic museum, the Moscow House of Photography, might never have appeared. In Rodchenko’s house, together with the Rodchenko family, we have discovered and studied the history of Russian photography, which would be unthinkable without Alexander Mikhailovich Rodchenko.

Olga Sviblova