100 shots of France — French photographs from beginnings to our days

Brassai, Valerie Belin, Atelier de Baldus, Rene Barthelemy, Theophile Feau, Alexandre Ferrier

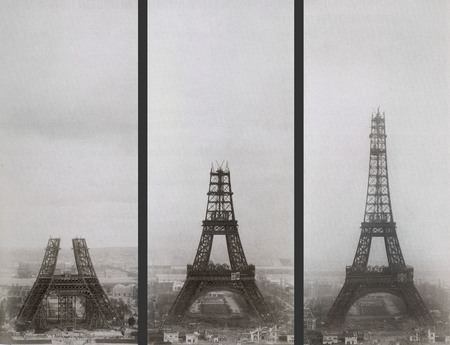

Theophile Feau. Building the Eiffel Tower . June 1888, 14 November 1888 and 20 January 1889 The Universal Exhibition of 1889 celebrated the centenary of the French Revolution. Parisian families went to admire the construction of the tower built by engineer Gustave Eiffel (1832–1923). Built to last only the duration of the Exhibition, it was saved in 1909 by the installation of a radio receiver at the summit. Modern print made in 2007 from the original proof in the Musee d’Orsay. Paris. Musee d’Orsay, Paris. A donation by Mme Bernard Granet and her children and Melle Solange Granet, Gustave Eiffel’s descendants. FEAU Theophile © Musee d’Orsay, Paris / dist. RMN 67

There are butchers. Plenty of butchers. Only the meat is missing. about 1943. During the war requisitions of straw and forage made it more difficult to feed livestock. In the occupied zone supplies of meat were increasingly difficult to come by. Butcher’s shops were empty. Original print. Gabriel Auboin collection, Paris. Anonyme © Haa /DR

General de Gaulle (1890–1970) arrives at the Hotel de Ville. August 24, 1944. The day after the liberation of Paris, General de Gaulle crossed the capital to visit Notre Dame Cathedral. Thousands of jubilant Parisians came to cheer the man who would be president from 1958 to 1969. On 25th August 1944 de Gaulle gave his famous speech: “Paris! Outraged Paris! Broken Paris! Martyred Paris! But liberated Paris!” Anonyme © Collection Gabriel Auboin, Paris / DR

Occupation of Paris. about 1942. There is no petrol left in occupied France. Everyone gets around on bicycles. People take each day as it comes. They still glue photographs of children, family and their daily lives in family albums. Original print. Anonyme © Haa /DR

Young people in a meadow. about 1936. France is paralysed by strikes. In June 1936 the new Popular Front government approved a law to adopt paid leave, a reduction in working times, union rights and compulsory schooling to the age of 14. This new paid gave more than 600,000 French workers their first holiday. Anonyme © Haa /DR

Atelier de Baldus. Decorative elements of the new Opera de Paris about 1873. Seventy-three sculptors work without interruption for the Opera Garnier. The rich facade stayed covered up during the work. The architect, Garnier, wanted to keep the surprise effect for the day of the inauguration. Salted paper was a printing procedure used from 1839 in which the photograph was obtained by direct blackening before being turned and fixed. Salted paper. BALDUS, Atelier de © Collection Gabriel Auboin, Paris

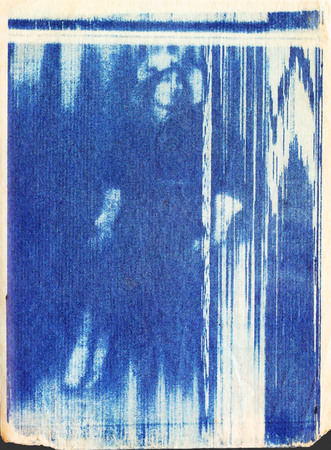

Rene Barthelemy. Reception of an image sent from the Poste du Petit-Parisien transmitter on top of the Eiffel Tower February , 1930 Barthelemy, the French engineer and pioneer in the development of television, transmitted the first images from the Eiffel Tower. The lines recomposed the subject transmitted. The cyanotype, a unique, economic and easy-to-use blue-coloured print, was mainly used by scientists and architects to document their work. Cyanotype. BARTHELEMY Rene © Collection Gabriel Auboin, Paris.

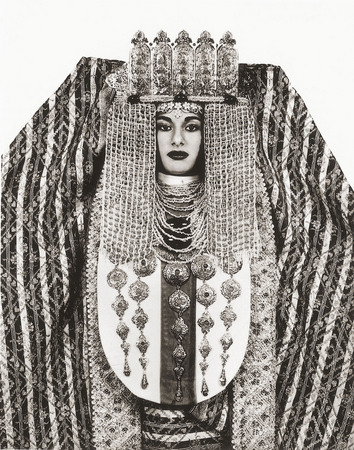

Valerie Belin. Untitled. 2000. Dressed and decorated, rich and sumptuous, the bride is transformed into a monumental sculpture. Indifferent or retiring, the Moroccan woman has disappeared under the “envelope” of her costume. Valerie Belin “writes” with the shadows of light. Her blacks are deep, her whites intense. Her photographic work plays with the body of the model and her internal nakedness. She is a mirror image. Exhibition print. BELIN Valerie © Valerie Belin

Brassai. Pair of lovers in a small Paris cafe, place d’Italie about 1932. Brassai loved the Paris of thugs, prostitutes, cabarets and unexpected encounters. The city of bars where lovers linger. He has slicked-back hair. She is smiling and in love. The mirror replicates their passionate fervour. The Hungarian Brassai arrived in Paris in 1924. A humanist photographer of genius, he was the first to pursue the secret and poetic world of Paris by Night, as seen in his famous book published in 1932. Modern еxhibition print. Brassai Estate, Paris. BRASSAI © Estate Brassai / dist. RMN

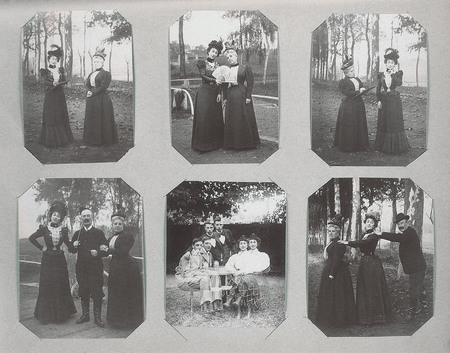

Family album. about 1895. In the family home the young lady of the house stages diverse charming and naive scenes. Because of the lack of light, most images were taken outside. They also made playful use of photographic “accidents”. All the images were carefully glued into family albums. Modern duplicate made from a page in the album. Anonyme © Haa

Alexandre Ferrier. Saint-Jacques Tower, Paris. about 1864. Located in the centre of Paris, the Saint-Jacques Tower is all that remains of a church destroyed during the Revolution. After prefect Haussmann’s urban reconstruction it graced a new street, the future rue de Rivoli. The albumen print is made from a thin sheet of paper covered with salted albumen (egg white) then sensitised with silver nitrate for a glossy satinesque appearance. Invented in 1850 and highly popular in the 1860s, the procedure was used until the early 20th century. Albumen print FERRIER Alexandre © Collection Gabriel Auboin, Paris

Yakutsk, 6.04.2010—10.05.2010

exhibition is over

Saha Republic National Art Museum (Yakutia)

9, Kirova street

Share with friends

Exhibition shedule

-

5.03.2010—23.03.2010

Khabarovsk

Far Еast Museum of Fine Arts

-

6.04.2010—10.05.2010

Yakutsk

Saha Republic National Art Museum (Yakutia)

For the press

‘What the photographer reproduces infinitely only takes place once: it repeats mechanically things that could never be repeated existentially.’ Roland Barthes.

The emotion felt by the whole world at the discovery of photography in 1839 is understandable. A dream had become reality.

This project tells a story that began officially in Paris and continues to this day.

The works presented were selected from thousands of prints kept in three major world collections: the French National Library, the Musee d’Orsay and the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

The exhibition was assisted by the French Culture Ministry, the Paris Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the Jacques Henri Lartigue Foundation, the Brassai Foundation, private collectors, the photographers and their descendants.

Each of these prints is accompanied by a text with the history of the photograph and photographer that also tells us something about France and the French, and Paris. Choosing a single print by each photographer has enabled us to show the work of artists all too rarely exhibited such as Edouard Baldus, Charles Marville or Auguste Collard, along with photographs by acclaimed geniuses like Nicephore Niepce, Louis-Adolphe Humbert de Molard, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Negre, Eugene Cuvellier, the Bisson brothers, Felix Nadar and Eugene Atget. There are prints by anonymous amateurs and also famous names such as Jacques Henri Lartigue or Count Robert de Montesquiou.

Photography cannot be fully comprehended without understanding technique. In the early years it was gradually developed by rich inventors passionate about taking pictures. With the evolution of technical mastery (reproduction of prints, shortening exposure time...) it was commercialised by talented photographers such as Felix Nadar or Mayer and Pierson. A tool for imperial propaganda under Napoleon III

But photography also straddles both art and science. In 1839 the minister and scholar Francois Arago predicted how it would soon assume a scientific role. This ‘repertory of images’ was sorted, classified, compared and analysed by the Henry astronomer brothers, Alphonse Bertillon the founder of the Parisian Legal Identity service, the psychiatrist Dr Raviart and physiologist Jules Marey. Duchenne de Boulogne, another physiologist, decided to give his ‘repertory of expressions’ to students of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Outstanding French photographers Charles Negre and Gustave Le Gray had been also painters. Respected artists like Eugene Delacroix or Edgar Degas used it to build a ‘repertory of iconographic poses’.

At the beginning of the 20th century pictorialists such as Constant Puyo hoped to achieve a result close to painting by their composition of photographic studies and by elements added during printing. After the chaos of the First World War the Surrealists played with technical experimentation. For Man Ray, Dora Maar or Raoul Ubac photography was no longer ‘representation’, but also the ‘purpose’ of the creation.

After 1930 humanist photographers such as Brassai, Andre Kertesz and Robert Doisneau went looking for a poetic Paris, the city of street urchins, louts and lovers. With the growth of the press, Janine Niepce and Sabine Weiss became photo reporters covering political and social news. Photography was omnipresent in magazines and books, walls were plastered with poster photographs. Fashion photographer Frank Horvat preferred the street to any studio. More and more agencies appeared. Amongst the founders of the Magnum agency in 1947, Henri Cartier-Bresson hunted for the ‘decisive moment’. Together with Martine Franck and Raymond Depardon the photographer directly controlled the use and commercialisation of his work. ‘Photojournalist’ Gilles Caron covered the latest news. Jeanloup Sieff scattered photographs like pebbles as he traced his personal story. Agnes Varda immortalised Gerard Philipe on stage at the Avignon Festival before concentrating on ‘contemporary’ creation.

In the last quarter of the 20th century photography was only one short step from the plastic arts. With Bernard Faucon, Patrick Tosani, Valerie Belin, Frank Perrin and Valerie Jouve photography became a creative medium used by conceptual artists. For Georges Rousse and Bernard Plossu it represents ‘memory’, Jean-Marc Bustamante transforms it into a ‘Tableau’, and Bertrand Lavier is not even a photographer.

In this exhibition we would like to emphasise the extraordinary vitality of a creative art that made its debut in France less than two centuries ago.

Above all the aim of this project is to enable every one of us to tell his or her own story.

‘Photography does not (necessarily) show what no longer exists, but only and certainly what has existed.’ Roland Barthes, ‘La Chambre Claire’, Note on photography, 1980.

Sophie Schmit Exhibition curator

NB: For purposes of conversation the historic photographs presented in this exhibition have been printed using contemporary techniques by owners of the originals, under their supervision.

Exhibition curator

Sophie Schmit is an art historian, journalist and independent curator. Her most recent exhibitions are ‘Paris in Shanghai. Three Generations of French Photographers’ (Fine Art Museum, Shanghai, 2005), ‘Odessa’s Ghosts’ by Christian Boltanski (Biennale of Contemporary Art, Moscow, 2005) and ‘The Third Eye. Photography and the Occult’ (Maison Europeenne de la Photographie, Paris,